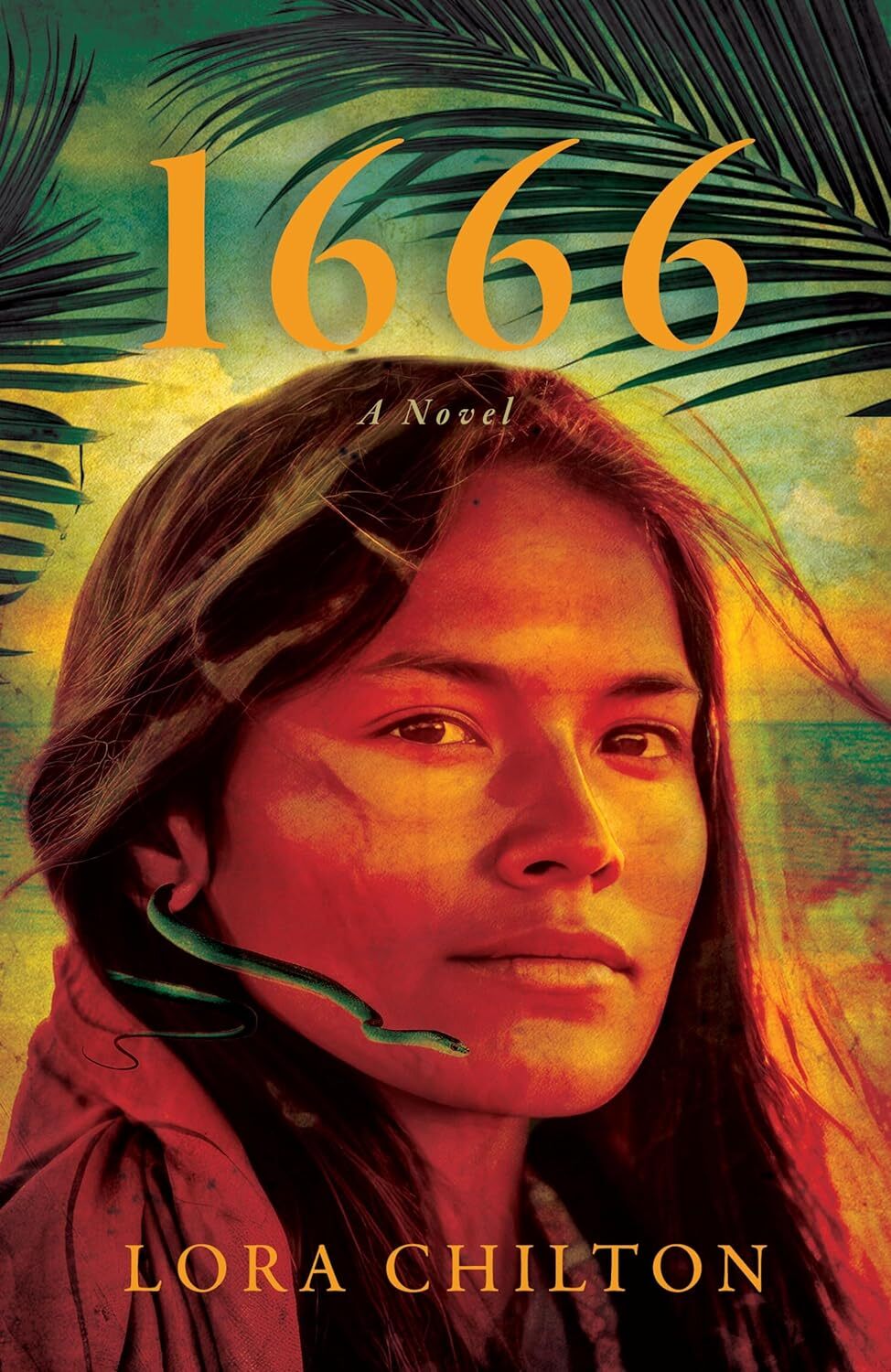

One of the most intriguing aspects of Lora Chilton’s historical novel 1666 may be the task of keeping the phonetically spelled names of people and places straight.

The story, based on a combination of what author Chilton refers to as “historical records and oral tradition,” is an inspired imagining of the struggle for survival of two members of the Indigenous Patawomeck (PaTow’O’Mek) tribe of Virginia (TseNaCoMoCo) following the attempted annihilation of the tribe by white colonial authorities in the year indicated by the novel’s title.

The primary characters, based on two women who may actually have existed, do indeed survive (though just barely), as, in the long run of history, has the tribe itself via surviving descendants, one of whom is Chilton herself. Her fellow Memphians may recall her as a prominent school board member and political activist (as Lora Jobe) of a few seasons back.

The aforementioned matter of phonetic spellings is really no obstacle to an immersion in the tale, functioning rather to ground one in a gripping sense of Being There in a present-tense reality. (And there are welcome recognitions, as when one of the story’s ultimate locations turns out to be a teeming place called MaNaHahTaAn (Manhattan).)

The main characters themselves have a variety of names. Ah’SaWei (Golden Fawn) is also Twenty-nine (her number as a freshly enslaved prisoner) and Rebecca (while serving in a Barnados household). And, similarly, NePaWeXo (Shining Moon) is Eighty-five and Leah.

To repeat, none of this gets in the way. For each of the characters, the identities are both discrete and overlapping. Each stands for a different phase of the characters’ destinies — Alternately horrific, heroic, and (relatively) mundane.

Those destinies occur within a meticulously outlined span of historical time in which the terrors and atrocities of the colonial era, described unblinkingly, are a basic part of the background and essentially define the course of events. But so, too, are the natural circumstances of life — love and sex prominently among them.

What did people of that milieu eat and how did they cultivate it? In what ways were their domestic tensions, coupling rituals, and emotional realities like or unlike our own? Chilton has researched it all and knows it in depth and can tell you.

And she does so with a dramatic, thriller-like sense of urgency that has us turning pages compulsively.

Some advance readers of the novel, whose blurbs are included with the text, focus on the story as “tragedy.” That’s a way of saying that terrible things happen and are accounted for graphically.

But what the story really is about is humanity’s unquenchable spirit and, as such, is the furthest thing imaginable from being a downer.