Memphis simmered in the July heat as a police cruiser pulled over a blue Nissan Altima motoring through the Downtown business district. The car’s temporary tag had expired days earlier, an oversight police often resolve by issuing a citation.

But this traffic stop took a more serious turn when a Memphis Police Department (MPD) officer said he “could smell an odor consistent with marijuana coming out of the vehicle.’’

After questioning a female passenger, police found slightly more than a half-ounce of marijuana in her purse — a small but critical amount that led officers to arrest the family-focused grandmother on a felony drug-trafficking charge.

As a special task force begins reviewing U.S. Justice Department claims of abuse by MPD during traffic stops, reform advocates say the woman’s arrest is yet another example of overly aggressive policing in Memphis.

“It’s absolutely a trumped-up charge,” said Claiborne Ferguson, a longtime Memphis defense attorney who reviewed the July 2, 2024, police affidavit filed against the woman. He has no official connection to the case.

The woman, a cancer victim, said she is no drug dealer and doesn’t even smoke that much.

“It was crazy,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified. Although the charge against her was later dropped, she said she fears any association with a criminal charge. “I’m a real-life good person. I treat everyone with respect,” she said.

The incident is one of 13 traffic-stop cases identified by the Institute for Public Service Reporting in which Shelby County law enforcement officers signed felony marijuana affidavits, only to see those charges vacated in court. Attorneys who reviewed the affidavits for The Institute said they appeared deficient in supporting felony charges of intent to sell.

The charges — which often involved warrantless searches of vehicles — led arrestees to spend several hours or more in jail.

“I lost my job,” said Dominique Hodges, 26, who was arrested in December. Prosecutors dropped the charges in February, but not before she spent a terrifying night at Jail East, Shelby County’s women’s holding facility, and paid $700 in attorney fees and costs. She said the charges hanging over her caused her to lose a good-paying maintenance job.

“I cried and I cried,’’ she said of her trip to jail. There, jailers conducted an invasive search, she said. Later, Hodges watched in fear as an irate arrestee hit her fist against a wall over and over. “I wouldn’t wish this upon my worst enemy,’’ she said.

Among the 13 arrestees, 12 were Black, including Hodges and the grandmother.

All the arrests were made after officers said they smelled marijuana and either requested consent to search or used the smell as probable cause to search vehicles without consent.

The 13 arrests included 10 by MPD, two by the Sheriff’s Office, and one by the Tennessee Highway Patrol.

Both MPD and the Highway Patrol declined comment. The Sheriff’s Office didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

A Memphis Police Department detective searches a car in October 2022 after officers said they spotted marijuana residue on the front console. Charges against the motorist were later dismissed at prosecutors’ request. (Photo: MPD Body Camera Footage)

Broad Police Discretion

The Institute identified the 13 cases while reviewing eight months of arrest data, including a six-month stretch between last April and September and a follow-up two-month stretch in December and January to assess patterns following the release of the Justice Department’s critical December 4th report.

Traffic stops reviewed by The Institute followed a general pattern: Motorists were pulled over for a missing headlight or taillight, tinted windows, expired or missing tags, failing to wear a seat belt, and occasionally for speeding or running a red light.

Officers then searched vehicles after saying they smelled marijuana.

Simple possession of small amounts of marijuana is a misdemeanor in Tennessee, which remains among a slim minority of states that haven’t legalized medicinal or recreational marijuana. In Shelby County, where marijuana prosecutions have been deprioritized, police can issue a misdemeanor citation for simple possession without making an arrest. At times, officers take no action at all when stopping motorists with small amounts of marijuana, according to interviews conducted by The Institute.

But a felony charge brings a guaranteed trip to jail.

Police generally have broad discretion when making arrests. Probable cause to arrest requires a lower threshold of evidence than proof required at trial, and police tend to charge suspects at the highest level available, defense attorneys said.

Attorneys who reviewed arrest affidavits for The Institute said some appeared to be borderline cases or “close calls” in establishing probable cause for a felony charge. In one case, a motorist charged with felony intent to sell was found with a small amount of marijuana and three guns, including a semiautomatic rifle. Records suggest it was a difficult matter to sort out: All the guns turned out to be legal. Tennessee doesn’t require permits to carry guns, and it allows most people other than individuals convicted of felonies to freely transport them in cars.

Such incidents require quick judgments often made under high-stress conditions, police say.

“It’s very tough because you don’t know what’s in that car,’’ said Mike Williams, a former patrolman and past president of the Memphis Police Association, a labor union. “I couldn’t imagine me personally being out there in the streets right now … because everybody has a damn gun. And a lot of these young people that are running around with these guns, they’re not afraid to use them.”

But reform advocates say there is a delicate balance between protecting public safety and eroding community trust. Even if a charge is later dismissed, arrests often pose hardships including job loss along with stiff fees and court costs. Often, vehicles are seized.

“So now because I get caught with this … I have to hire a lawyer. I have to go pay a bond. Get probation,’’ said Keedran Franklin, a criminal justice reform advocate who contends police often target people of color. “That … may put me $30,000 in debt.’’

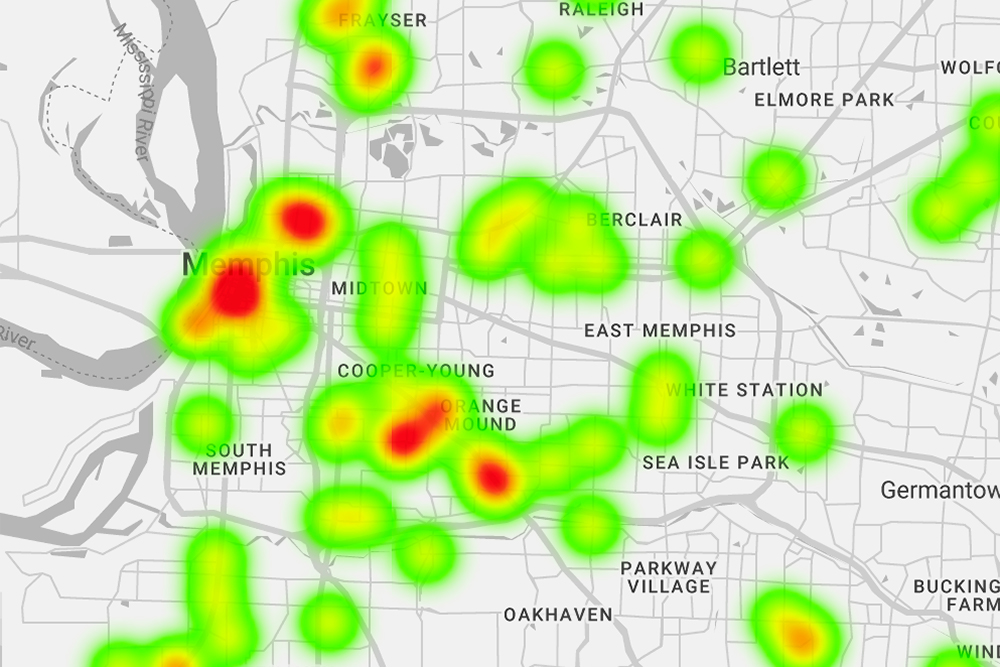

Overall, African Americans represented 89 of 93 Shelby County defendants (96 percent) identified by The Institute as having been arrested between last April and September after officers said they smelled marijuana. Many of the traffic stops, which often led to charges unconnected to marijuana possession, were clustered in African-American neighborhoods in Orange Mound, Frayser, Hickory Hill, and South and North Memphis.

MPD’s focus on saturation patrols in “high-crime” neighborhoods and the potential for harassment alarmed Justice Department officials, who noted in the December 4th report that Memphis police stopped one Black man 30 times in three years.

Shelby County District Attorney Steve Mulroy said police need discretion when making arrests but conceded that evidence at times can’t support felony charges.

“It is not at all uncommon for the police to bring us a charge for felony intent to sell marijuana and we reduce it to a misdemeanor. And largely that’s not necessarily because we’re saying that the police over-charged but because there is a difference between the amount of evidence you need for probable cause to arrest and the amount of evidence you need to prove something beyond a reasonable doubt at trial,” Mulroy said.

“So I’m not going to use a heavily charged word like abuse, but I will say that given the fact that the arrest itself can be disruptive to someone’s life, and given that it seems like this particular charge seems disproportionately targeted on the African-American community … one can see how a really aggressive posture of arresting and charging felonies for what may simply be simple marijuana possession can be problematic. It may be something that maybe this task force can look at.”

The task force formed when Mayor Paul Young tapped former federal Appeals Court Judge Bernice Donald to review Justice Department allegations outlined in its December 4th report. The 70-page report found MPD often conducts unlawful stops and searches, discriminates against Black people, and uses excessive force.

Small Amounts, Big Charges

It was three days before Christmas, and Dominque Hodges was out partying with friends. They took her battered Chrysler Sebring, though she was riding as a passenger that night. When police spotted the car — missing rear bumper, burned-out front headlight, invalid drive-out tags — they pulled it over.

“They snatched me out of the car,’’ Hodges recalled.

According to her arrest affidavit, police searched the car after smelling marijuana and found a bag containing 18 grams, roughly enough to roll 18 to 36 marijuana cigarettes. Hodges said she admitted the pot was hers, arguing that she’s a smoker not a dealer.

“I’m telling them, ‘Why am I going to jail for this little bit? … Look, my mom is sick. I don’t have nobody that’s going to come and bail me out of jail.’’’

Under Tennessee law, a person who possesses a half-ounce (14.175 grams) or more of marijuana with the intent to manufacture, sell, or deliver is guilty of a felony punishable by 11 months to 60 years in prison depending on the amount and an individual’s prior record. Selling less than a half-ounce is a misdemeanor.

But defense attorneys say many officers don’t seem to understand that simple possession — even in amounts greater than 14.175 grams — is still a misdemeanor if the defendant lacked intent to sell.

“I have regularly heard officers and prosecutors say more than half [ounce] is a ‘felony amount’ but that is incorrect,’’ said Ben Raybin, a Nashville-based defense and civil rights attorney. “There still has to be an intent to sell, deliver, or manufacture.’’

Courts have ruled that to prove intent, authorities need evidence of something more than mere weight. They need other supporting details such as finding marijuana packaged in multiple baggies, large amounts of cash, firearms, ledgers, digital scales, or other indicators of a drug sale.

Yet repeatedly, records show, officers arrest motorists on charges of felony intent to sell marijuana with scant supporting evidence of an indication to sell — charges that are later vacated in court. The cases reviewed by The Institute were dropped by prosecutors via an action known as nolle prosequi, or the abandonment of a criminal charge.

In the July 2, 2024, arrest of the grandmother in Downtown Memphis, for example, police reported finding 16.1 grams in her purse. In an affidavit of complaint sworn out before a judicial magistrate, police listed no other evidence indicating an intent to sell. The woman was booked into Jail East, Shelby County’s detention facility for female arrestees. The charge was later dropped.

“I don’t see the slightest hint of evidence that she possessed it with the intent to manufacture, deliver, or sell it, so in my opinion this should have been charged [with] a misdemeanor rather than a felony,’’ Raybin wrote in an email. “If that was her only charge [as it was], she should have been given a citation rather than placed under a custodial arrest.”

Defendants charged with misdemeanors often are cited and released without being booked into jail. In some instances of simple marijuana possession, officers don’t even do that much, some allege.

“Most of the times [when] we get stopped, the police put the weed right back in the car,” Hodges said.

Recently retired General Sessions Court Judge Bill Anderson said that he’s heard similar accounts.

“It’s gotten out to the rank-and-file police on the street that the DA is not prosecuting small amounts of marijuana,’’ Anderson said. “These officers … don’t like coming to court. They don’t like wasting their time having to write report after report. So if it’s a small amount, what I understand they’re doing is just throwing it away or telling them, open it up, throw it out on the street or something.”

Overall, officers seize relatively small amounts of marijuana when making traffic stops on Memphis streets.

Among the 93 odor-triggered arrests identified by The Institute, the median amount of marijuana confiscated was 20 grams. That’s roughly enough to roll 20 to 40 marijuana cigarettes.

Studies suggest traffic stops like these aren’t effective in reducing overall crime rates, but they can accumulate significant arrests. During one three-day stretch in June, The Institute found, MPD arrested at least 10 people after smelling marijuana, including five with violent arrest histories and another with glassy eyes and slow reactions who was charged with driving while intoxicated by marijuana.

In those 10 arrests, police confiscated two assault-style rifles, a Glock 17 handgun with a switch that converted it to a rapid-fire machinegun, and three other pistols.

Questions surround MPD’s supervision and training

Marijuana grown today is much more potent — and pungent — than in years past. Its smell wafts across Memphis, emanating from cars, seats at Tiger football games, street corners, and alleyways.

Still, attorneys interviewed for this story said they believe police at times manufacture claims that they smelled marijuana as a pretext to create probable cause to search a vehicle.

The Justice Department report articulated similar concerns.

“While officers often justify vehicle and pedestrian searches based on statements that they have smelled the ‘odor of marijuana,’ courts and MPD’s own internal affairs unit have found that those justifications are not always credible,’’ the report said.

“… A prosecutor described MPD’s explanations as sometimes ‘cringey’ and gave the example of an officer claiming to have smelled marijuana in a car that was going 60 miles per hour.”

It’s difficult to assess how widespread the problem may be.

“The problem is, I don’t know [the full extent of] the abuses because nobody’s forcing them to keep up any records of when they search a vehicle saying they smelled marijuana and not finding anything,” Ferguson said.

Again, the Justice Department articulated similar concerns.

“This data does not include hundreds of thousands of traffic stops that did not result in citations because MPD officers do not document the reason for those stops,” the report said.

But the report was unequivocal in stating that MPD engages in a pattern of illegal traffic stops, arrests, and evidence collection in violation of the Fourth Amendment that protects citizens against unreasonable search and seizure.

“The pattern of Fourth Amendment violations stems from MPD’s decision to prioritize traffic enforcement as a central method to address crime in Memphis, while at the same time failing to ensure that officers understand and follow constitutional requirements when they stop and detain people,’’ said the report, which followed an 18-month investigation launched after the January 2023 police beating death of motorist Tyre Nichols.

“… Supervisors rarely review traffic stops to ensure they meet constitutional standards. But they do measure officers’ ‘productivity’ based in part on how many stops and citations they generate.’’

Ferguson said he believes MPD’s struggles stem from either poor training or coaching by supervising lieutenants.

“It’s either bad training or it’s purposeful malicious prosecution in order to seize vehicles. That’s all it can be,’’ Ferguson said. “Either they’re completely not training these officers or they train them specifically to do this to get into the car.”

The Justice Department Raised Similar Concerns

“Officers will, for example, write in reports that they smelled marijuana, but there will be no mention of the odor of marijuana on body-worn camera footage,’’ the report said.

Such a scenario played out in federal court last year when prosecutors dismissed gun charges against Cedric Jackson, now 33, after inconsistencies arose between police reports and body camera footage.

Officers wrote in an October 2022 affidavit that they “observed a green residue consistent with marijuana’’ on the console of Jackson’s Chevy Tahoe. Citing that as probable cause to search the vehicle, officers found a Smith & Wesson handgun that Jackson, a convicted felon, could not legally possess.

“I am having trouble with the search,’’ U.S. District Court Judge Thomas L. Parker said in a January 4, 2024, hearing after reviewing bodycam footage. “… If they were relying on noticing the residue of marijuana on the console, I didn’t hear anybody say so at the time. I watched several videos and so I did not … see a lot of discussion about that. There were no photographs of the residue on the console area, so the court finds that the government did not carry its burden to show that that was the basis for a search.’’

Though Parker later dismissed a defense motion to suppress evidence seized in the search, finding the items would have been detected later in a routine inventory search of the car, the case’s credibility appeared shaken by defense challenges. Parker eventually approved a motion by prosecutors to dismiss the case.

Asked why prosecutors moved to dismiss the case, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Memphis declined comment.

Evolving Marijuana Laws

Odor-related searches have grown complicated in Tennessee, in part because of law changes in other states. Tennessee is one of just 11 states where recreational or medicinal marijuana use hasn’t been legalized, according to the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. Yet motorists on Memphis’ streets may be carrying medicinal marijuana bought across the river in Arkansas or across the border in Mississippi. Recreational marijuana can be purchased via a short, 90-minute drive into southern Missouri.

“Now [when they return to Memphis] they’re presumed to be a felony drug dealer,’’ said defense lawyer Michael Working. “… You’re coming back with more than 14.175 grams every time. It’s like, you know, you don’t go to Arkansas to buy legal beer and buy [just] one can of beer.”

In Shelby County, simple possession of small amounts of marijuana often is tolerated.

District Attorney Mulroy said simple possession prosecutions had been deprioritized by his predecessor, Amy Weirich, though the practice varied among individual prosecutors, he said.

“I think it’s more uniform now [in] that it is not a priority,” Mulroy said. “We still enforce it. I mean, it’s the law, right? We enforce it. But we’ve got so many more important things to focus on, like violent crime.” Though there is “no blanket rule,” misdemeanor marijuana cases can lead to community service followed by a dismissal of the charges, he said.

Consequently, police often won’t bring misdemeanor cases, defense attorneys said. What’s emerged is a sort of felony-or-nothing situation. And as courts have trimmed back on Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure, the smell of marijuana as justification to search a vehicle has become all but impossible for defendants to overcome, defense attorneys say.

But a Tennessee Supreme Court ruling last summer may change some of the ground rules for marijuana-related traffic stops.

In that case, State of Tennessee vs. Andre JuJuan Lee Green, the court ruled that the smell of marijuana alone is not enough for a search, finding that officers must consider “the totality of the circumstances” before conducting a warrantless search.

That case originated from Clarksville, Tennessee, where officers used a drug-sniffing dog to find an ounce of marijuana, baggies, and a gun during a February 2020 traffic stop. Defense attorneys argued the search was improper because a police dog can’t tell the difference between legal hemp and illegal marijuana. Both are varieties of the same species. Congress legalized hemp in the 2018 Farm Bill and Tennessee followed suit in 2019.

The court rejected a defense motion to dismiss the case. Although it found that “the legalization of hemp has added a degree of ambiguity to a dog’s positive alert,” it ruled the search was merited by a totality of circumstances that included “suspicious answers” that the car’s occupants gave to officers’ questions and a backpack seen in plain view inside the car. Both the car’s driver and passenger denied ownership of the backpack.

Raybin said the Green case means officers will no longer be able to conduct probable cause searches of vehicles based solely on the odor of marijuana.

“In my opinion that is directly precluded by the Green case and everything should be thrown out,’’ said Raybin, who co-authored a friend-of-the-court brief in support of dismissing charges in the case.

How much actual impact the ruling will have remains to be seen, however. Officers don’t need much in the way of additional factors to justify a search, Raybin said. It can involve something as simple as a defendant appearing nervous, “sweating profusely,” or making inconsistent statements.

“… It still won’t take too much’’ to justify a search, Raybin said.

Data for this story comes from public records kept by Shelby County’s criminal courts on behalf of Shelby County residents. The county makes individual records available. These records were compiled and processed with a web programming tool that enables a user to efficiently compile and see all of the public records, and sort them to identify and analyze arrest patterns. The sortable records are kept on a server maintained by a criminal justice reform group, People for the Enforcement of Rape Laws. The Institute for Public Service Reporting (IPSR) pays a license fee to access these records and cover the cost of programming and maintenance. IPSR independently verifies the data through computer analysis, spot-checking, and other methods. The reform group has no input or ability to influence the reporting of these public records. IPSR retains full authority over editorial content to preserve journalistic integrity.