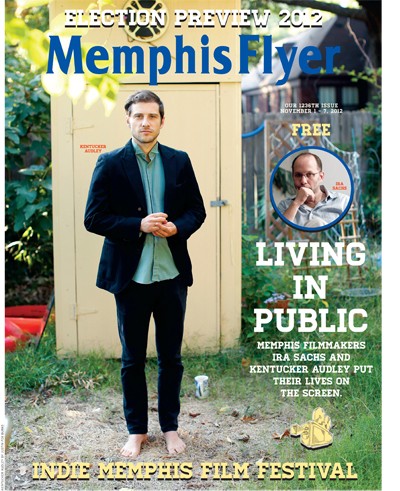

It’s January 30, 2005, in Park City, Utah, the last day of the Sundance Film Festival, and the greatest single day in Memphis film history. Craig Brewer, having just accepted the Audience Award for Hustle & Flow, has retuned to his seat just in time to hear the winner of the Jury Award announced: 40 Shades of Blue, directed by Ira Sachs.

“When they announced Ira, I embarrassed myself. I let out this scream, and I leapt off of my seat,” Brewer recalls. “I couldn’t believe it. Two Memphis filmmakers, with two Memphis films, just took the two top prizes at Sundance.”

It wasn’t Sachs’ first Sundance. In 1997, The Delta, his coming-of-age story of a gay teen in Memphis, had screened at the festival to great acclaim. But the indie film business being what it is, it took him eight years to get back to Sundance, coincidentally the same year as Brewer, his friend and fellow Memphian.

“Out of all of the filmmakers I know, he’s my hero,” Brewer says. “He’s held to his style through a challenging time in independent cinema. The individual auteur is not rewarded in this global marketplace.”

* * *

It’s 10 a.m. on August 22, 2014. Ira Sachs sits in his Greenwich Village apartment as the first commercial screening of his new film Love Is Strange is happening in New York City. “It feels great,” he says. “It’s been a long road to get here, but now it’s in other people’s hands. It’s with the audience.”

Sachs’ new film has been gathering buzz on the festival circuit ever since its debut at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival, where Memphis filmmaker Morgan Jon Fox was in the audience “I saw about 10 to 12 movies that were incredible, but only one of them got a standing ovation, and that was Love Is Strange,” he says. “As a director trying to make movies about queer culture, Love Is Strange is one of the most important and affecting films I have ever seen.”

Sachs has been gently deflecting this kind of hyperbolic praise for his film for the past nine months. “Real personal reactions to this movie are what I was hoping for, and what I am seeing,” he says. “I think people go into it expecting one thing, but then they find that it’s a portrait of a family, and in that way it is a portrait of all of our lives. It’s very much about the different stages of life we go through and how love looks differently in each one. I feel very differently about the possibilities of love as a middle-aged person than I did when I was 20.”

* * *

Like Brewer, Sachs’ Sundance win resulted in the opportunity to work with a much bigger budget. Sach’s 2007 film, Married Life, was a finely crafted, 1940s period piece starring Chris Cooper, Rachel McAdams, and Pierce Brosnan. It cost $12 million to make, but earned less than $3 million at the box office.

“I had to reinvent myself,” Sachs says. “You have to keep assessing what is possible and recalibrating your strategy about how to keep going.”

Sachs’ 2012 film, Keep the Lights On, couldn’t have been more different. It was an abandonment of the Hitchcockian style Sachs toyed with in Married Life and a return to his indie roots. The raw, unflinching story of a doomed love between a filmmaker and a drug addict spiraling out of control was as harrowing a bit of autobiography as has ever hit a screen.

“Each film is really an expression of where I am at that moment in my life,” Sachs says. “The movie is somehow a way to translate that into a story. I began working on Love Is Strange in January 2012, with my co-writer Mauricio Zacharias. That was a point when I went from living alone in my New York apartment to living with my husband, our two babies, their mom, and occasionally visiting in-laws. So the idea of a multi-generational family story told inside a cramped New York apartment seemed like a good idea.”

* * *

Alfred Molina first heard of Love Is Strange when his agent gave him the script. The 61-year-old actor, whose big break came playing Indiana Jones’ ill-fated guide in the opening sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark, has been in comedies and dramas, films large and small. But he knew this little $1.5 million film was going to be something special.

“It’s a story about how love survives,” he says. “Anyone who is in love, or anyone who has fallen in love, regardless of who or how, can relate to that.”

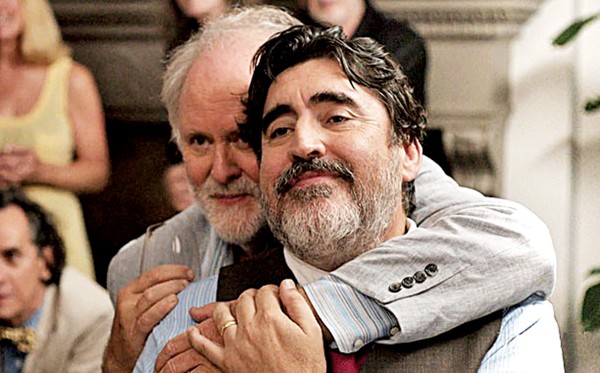

The story opens with George (Molina) and Ben (John Lithgow), a couple whose easy rapport speaks of a long and fulfilling relationship, getting ready in the morning. After decades together, it’s a day neither thought they would ever see: Their wedding day.

“The refreshing thing from an audience’s point of view is that whenever you see love stories, it’s almost always at the younger end of the age spectrum,” Molina says. “It’s couples struggling to find themselves, to find each other, to find their place in the world. But these characters are in the autumn of their years, and after many, many years of a committed relationship, they suddenly find themselves in crisis.”

George is a music teacher at a Manhattan Catholic high school. His homosexuality has been an “open secret” for years, but now that he and Ben, a 71 year old who has retired to his painting, have made it official, his boss can no longer shield him from the diocese, and he is unceremoniously fired.

In the hands of another writer/director, that would be the story: a gay couple, finally granted their right to wed, continues their fight against the forces of intolerance and discrimination. There would be protests and perhaps a climactic court scene with George and Ben giving stirring speeches about tolerance and acceptance, ending with a favorable verdict and applause. But that’s not Love Is Strange.

“In real life, people don’t have those big scenes,” says Molina. “You never have those cathartic moments where you let everything out and you make a great speech that encompasses your life. That’s why Ira’s so brilliant, because he’s not afraid to be truthful about it.”

Sachs says he takes inspiration from Italian Neo-Realist filmmakers such as Michelangelo Antonioni. Working in postwar Italy with very few resources, Antonioni’s films concentrated on the mundane details that would be cut from a Hollywood production in favor of sweeping but artificially heightened drama. “We have very dramatic lives without necessitating melodrama,” Sachs says. “The things that happen to us in the course of our lives are major, even if they’re described in a minor key.”

Without George’s income to support them, the couple is forced to sell their apartment and separate. Ben moves in with his nephew Eliot (Darren E. Burrows) and his wife Kate (Marisa Tomei), sleeping on the bottom bunk bed in his great nephew Joey’s (Charlie Tahan) room. George crashes with some friends, a pair of gay policemen who love to play Dungeons and Dragons and throw parties.

“He uses the injustice as a device to explore the human condition in other areas,” Brewer says. “Love Is Strange is probably Ira’s most subversive film because it’s so accessible. It moves you on a human level, and doesn’t hit you over the head with politics. That’s what makes it so compelling. In a way, it quickly stops being a movie that explores gay issues and becomes a movie about old love and commitment, and especially about what some people are having to face in this current economy.”

After reading the script, Molina was the first actor to sign on to the project. “It went through all of the usual vicissitudes and stumbles along the way that independent film is subject to,” he says. “But I stayed with it because I liked the script so much.”

* * *

Sachs says the character Ben was inspired by Memphis artist Ted Rust. “Ted was my great uncle Ben Goodman’s partner for about 45 years. I had the opportunity to really get to know him well. He’s a guy who, at 98, began his last sculpture, which was of a young teenager with a backpack on. At 99, he died, and the piece remained unfinished. But to me, the idea of a man pursuing his passion and creativity until the last minute seemed extraordinary.”

In Love Is Strange, Ben finds solace in his painting, even as the life he has built with George crumbles around him. “It’s about the uncompleted sense of possibilities that an artist, or any of us, can have. It’s something we can strive for,” Sachs says.

As Sachs struggled to raise money for his film, he managed to land a great cast. Tomei signed on for the important role of Kate, a writer whose long-suffering kindness is tested when Ben moves in. For Ben, Sachs landed the legendary Lithgow. “I brought Lithgow in, with the approval and encouragement of Molina,” the director says. “They had been friends for 20 years in the same social circle in Los Angeles. Once we started working, they were like kids who met at summer camp who had been reunited. They had so much history to talk about, and so much common life between them.”

Once on set, the chemistry between the two lead actors was effortlessly real. “I think the fact that we’ve been friends for so long certainly helped,” Molina says. “We didn’t have to spend any time creating a shorthand. We made each other laugh a lot.”

Sach’s on-set technique is unusual. The actors come to the set with their lines memorized, the scene is blocked out, and the cameras roll. “Everything is emotionally improvised,” Sachs says. “The text is there, and they stick to it, but we’ve never rehearsed before we start shooting, and they’ve never heard another actor say a line. It’s a strategy I’ve worked with ever since the days of 40 Shades of Blue. Film is really about the filming of what’s happening in a moment, and it doesn’t need to be repeated. I find that you get the most spontaneous performances when you don’t talk too much before hand.”

From the beginning of his career, actors have responded enthusiastically to Sachs’ direction. “He creates a very pleasant, very respectful atmosphere on a set,” says Molina. “He’s not a shouter. He’s not standing behind a video screen screaming ‘Do it again!’ He’s very quiet and unobtrusive.”

If, like most people, your image of Molina is of Doctor Octopus in The Amazing Spider-Man 2, and your image of Lithgow is the manic alien invader from Third Rock from the Sun, you’re in for a shock. Molina’s George is the breadwinner, quietly struggling through repeated indignity to find a place where they can recreate their lives, until one wrenching scene where he shows up on Eliot’s and Kate’s door to cry into Ben’s arms. Lithgow’s Ben is kind, centered, and empathetic, but his immersion in his art makes him myopic. Together, they’re beautiful, inspiring, and heartbreakingly real.

“I have yet to see a performance this year that bests either Molina or Lithgow,” says Brewer.

* * *

Sachs’ first movie was a short called Vaudeville, about a group of traveling performers. “All of my films have been about friendships, but in the context of community,” he says. “To me, you can’t separate the two.”

Love Is Strange

Love Is Strange‘s New York setting provided many natural details. George’s hard-partying cop friends are inspired by a couple who were living upstairs from Boris Torres, Sachs’ husband, when they first met. “This kind of Tales of the City communal living is very wonderful and how we get by in our lives,” Sachs says. “The most important thing to me in New York is the relationship and the family I create for myself — both the biological family and otherwise.”

Sachs says Memphis’ contribution was more subtle, and more profound. “Memphis is a real inspiration. You think about the great music and art that’s come out of that town. What’s more entertaining than the Staple Singers or Isaac Hayes? But they have emotional depth. Jim Dickinson is a perfect example. He’s like Falstaff. He’s a perfect mix of drama and comedy.”

Love Is Strange is a dramatic film structured like a comedy, starring three actors with impressive comedic chops. Sachs compares it to 1930s comedies of remarriage, such as It Happened One Night, where a separated couple struggles to reunite. “It’s the structure of the Shakespearian comedy. I felt really fortunate to work with these extraordinary comic actors in the movie. It is a dramatic film, but there is a lot of lightness, because of the genius timing and effortlessness of actors like Marisa Tomei and John Lithgow. They brought a little levity to serious situations.”

Lithgow and Tomei are two actors who, like the late Robin Williams, can swing easily between comedy and drama. “I think it’s their timing, and I think it’s very lifelike to bring humor into a situation. It’s one of the shades of experience. It’s also pleasurable. This is maybe the most entertaining movie that I’ve made. That doesn’t mean it’s less deep, it just means people have an easier relationship with it. They’re happy to be there.”

* * *

Where Sachs’ Keep the Lights On was a sexually explicit film of passionate love gone bad, Love Is Strange is a meditation on long-term love, with nothing more sexual than a cuddle in a bunk bed between two fully clothed old men. And yet, somehow, both films have the same rating from the MPAA: R. Why? Is the mere fact that the lead characters are gay enough to earn an R rating in 2014?

“It’s totally unjustified,” says Morgan Jon Fox. “It’s a sham. It’s absurd that there are films that are far more violent or that have content that is far more detrimental that do not have an R rating.”

Brewer first saw the film before it was rated at the Los Angeles Film Festival. “I didn’t know it was going to be an R. What is the cause for the R rating? There’s nothing in that movie that is vulgar.”

Still of Charlie Tahan, Darren E. Burrows, and John Lithgow in Love Is Strange

Sachs is puzzled by the inappropriate rating, but remains, as always, unflappable.”It doesn’t upset me, except for the fact that this is a film about family, and it seems like it’s shutting off people who would get a lot from it. For better or worse, it’s a family film.”

Fox is more blunt in his assessment of the politics surrounding the rating. “To see two adults who are happy, who have been in a relationship forever, these are the kinds of role models that young queer kids need. But it’s so clear what they’re warning parents about, and that’s love. Warning: Your child may be influenced by love.”

* * *

“We’ve had terrific feedback,” Molina says. “The response from critics has been very positive, and audiences have loved it. I think it proves very clearly that there’s an audience out there for movies that are a bit more sensitive, a bit more challenging. It’s been very gratifying to see how people have responded to it.”

When Love Is Strange comes to Memphis for a premiere with the director on Friday, September 26th, it does so with the wind at its back. It’s currently sitting at 98 percent positive reviews on the film critic aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes; its $1.5 million budget was paid back with foreign rights sales at the Berlin Film Festival before it had even opened in America; and it has been very successful in limited release.

But it is the film’s message of love that Sachs says he wants his own two toddlers, Viva and Felix (“‘Life’ and ‘Happiness’, which they are.”), to take with them in life. “I was in Memphis a few weeks ago, and on Saturday I said, ‘Let’s have a potluck’, and on Sunday I had 10 pies and four batches of fried chicken. That’s love.”

And not at all strange.

Love Is Strange premieres Friday, September 26th at Malco Ridgeway Cinema Grill. Ira Sachs will be in attendance for a Q&A.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks