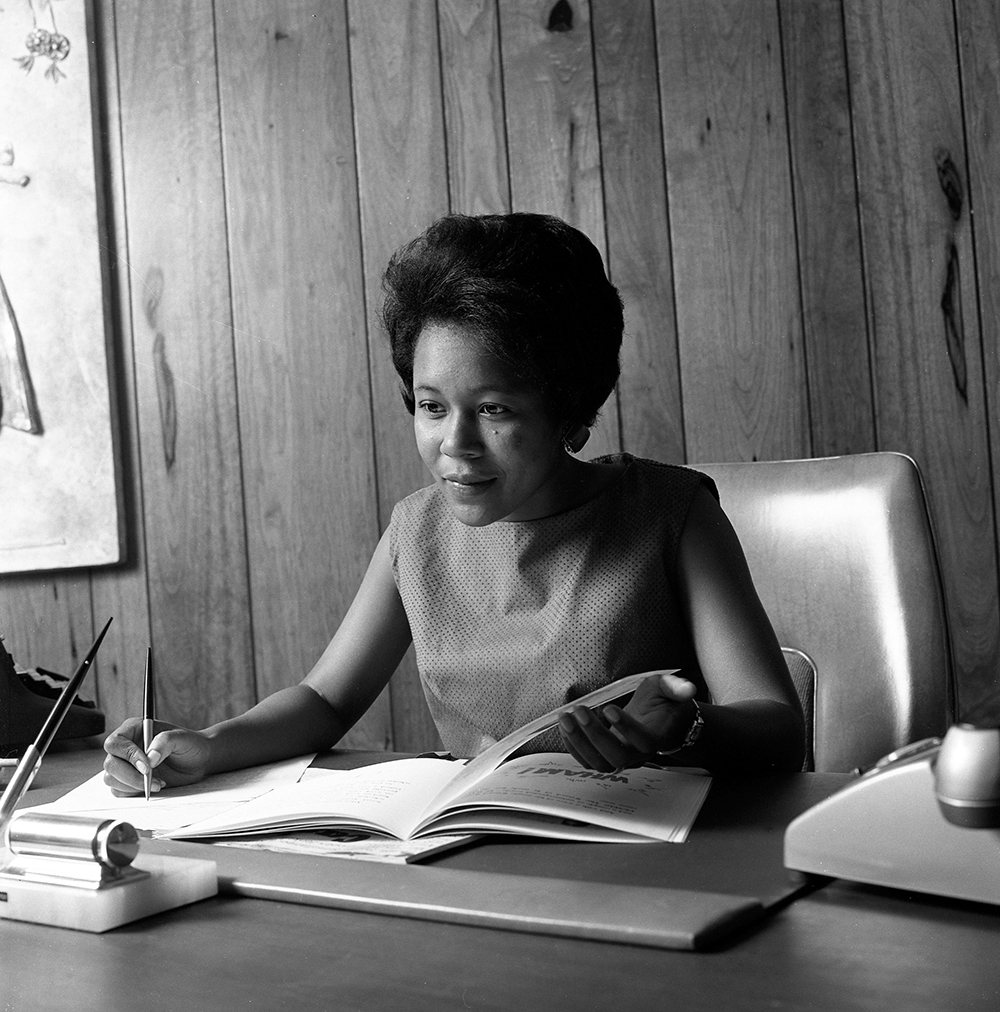

Back during the initial flowering of Stax Records, as the label went from success to success in its first half-dozen years, and all its rooms buzzed with an ever-expanding staff trying to keep up with popular demand, one star in particular had a tendency to saunter away from the studio, where the action was, and take a detour down Stax’s back hallways from time to time. Deanie Parker, one of the label’s first office employees who soon became their lead publicist, remembers it well — that’s where she worked.

“Every now and then, he just walked in the door,” she recalls a little wistfully, “with little gifts for the girls in the office, little packages. That’s the kind of person he was.”

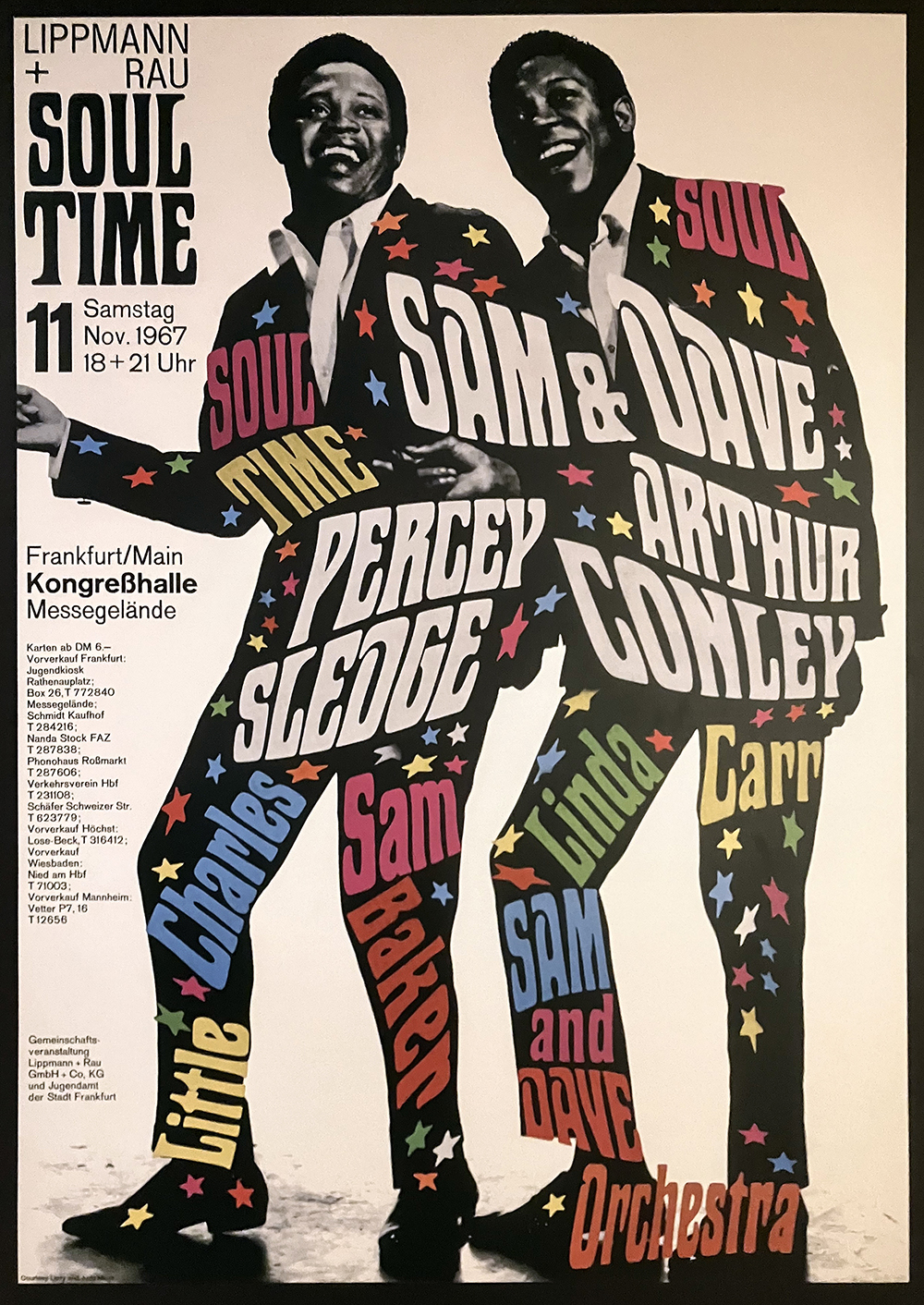

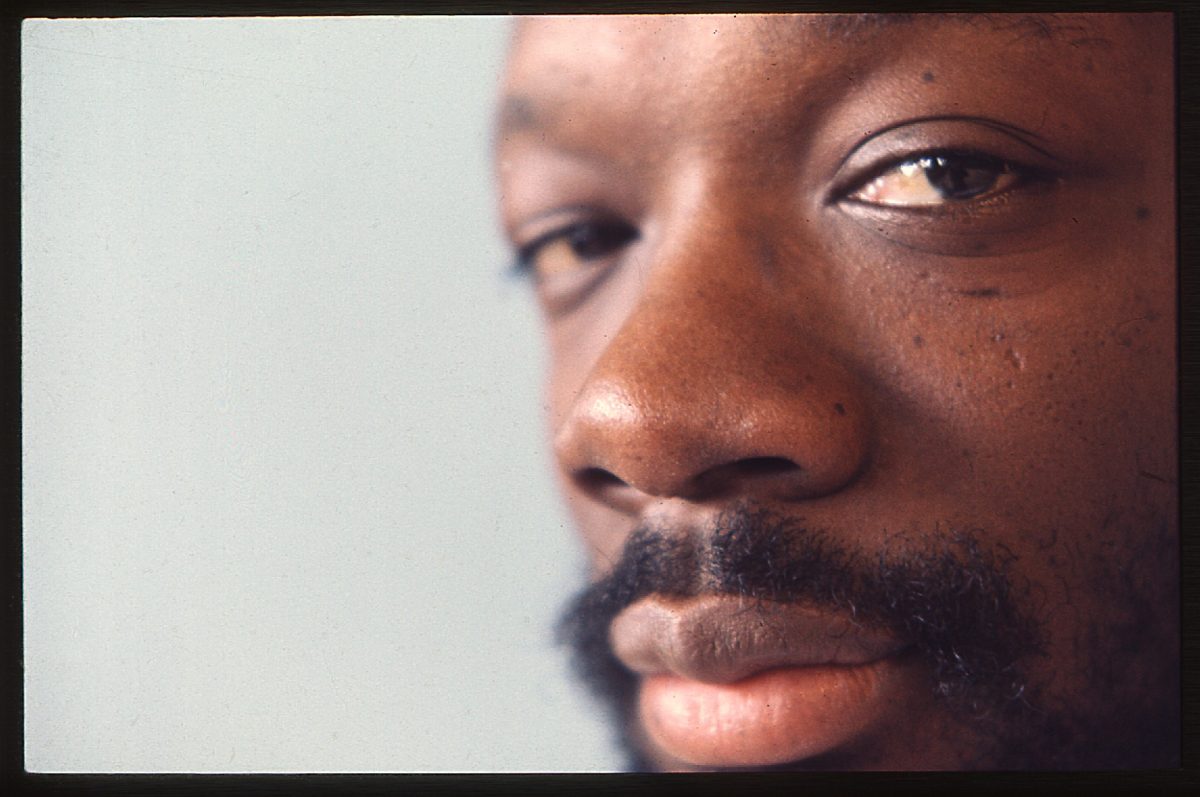

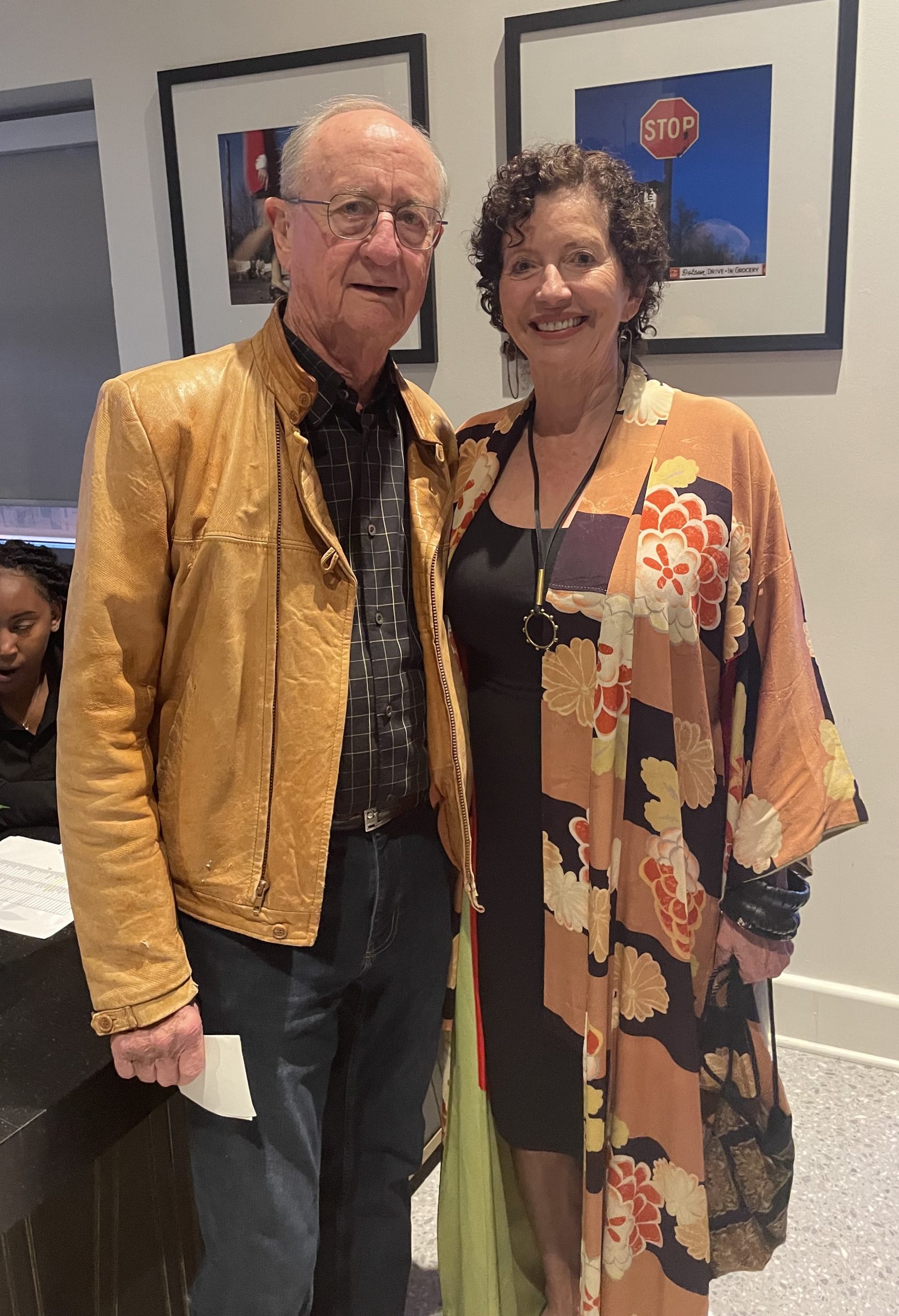

Now, scores of mourners will be sending flowers to that same soul singer, Sam Moore, the high tenor partner of Dave Prater in Stax super duo Sam & Dave, who died at the age of 89 on January 10th in Coral Gables, Florida, from post-surgery complications. This week, we pay tribute to the great Sam Moore by revisiting the pivotal role he played in the history of Stax and all soul music, as remembered by two who were right there with him: Deanie Parker and David Porter.

Sam Moore: The Stax Years

The quieting of one of soul music’s most expressive voices sent powerful shock waves throughout the music world — certainly among his late-career collaborators like Bruce Springsteen, but not least in Memphis, where Moore and Prater, singing the songs of Porter and Isaac Hayes, helped bring the Stax sound to its fullest fruition in the mid-’60s, becoming overnight sensations with hits like “Hold On, I’m Comin,’” “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “I Thank You,” and “Soul Man.”

Even then, “Sam Moore got along especially well with the administrative staff,” says Parker, recalling those spontaneous gifts. “He was the most gregarious of the duo. He was a great conversationalist and very personable. Dave was rather laid-back, kind of quiet.

“Keep in mind, now, that I was not in the studio with him all the time because I was in administration,” Parker goes on. “But because of our proximity to each other, it gave me an opportunity to get up and, when the record light was not on in Studio A, go in and observe and listen — not only to their rehearsals, but to the final takes and the playback.”

Surely anyone at Stax was rushing down the hall to hear the hot new duo’s latest, once the hits were hitting, for they were taking the Stax recipe to a whole new level of artistry. Yet while those songs are now part of the Stax canon, the definitive statements of the Memphis Sound, the success of two newcomers named Sam & Dave was not a foregone conclusion when they arrived.

Newcomers

“There was no one interested in Sam & Dave,” songwriter David Porter told Rob Bowman in the liner notes for The Complete Stax/Volt Singles: 1959-1968. “It was like a throwaway kind of situation [to] see if anything could happen with them.” Indeed, it seemed no one at Atlantic Records, who had a distribution deal with Stax, knew what to do with this singing duo from Florida, who’d had little luck with their scattered singles on the Marlin, Alston, and Roulette labels. Despite this, said Porter, “I was very much interested in Sam & Dave.”

But were Sam & Dave interested in Memphis? Atlantic had “loaned” the duo to the smaller label that was showing so much promise, but in 1965 Stax was hardly a household name. Moore’s reaction, according to Parker, was, “Who wants to go to Memphis?” Moore had his sights set on crossover pop stardom in the Big Apple, not moving to what seemed like a backwater. “He really did not have a positive impression about Memphis,” Parker says. “And apparently he was not all that familiar with Stax, which stands to reason, because when Sam & Dave got here, we only had a couple of stars. We just had Rufus and Carla, Booker T. and the M.G.’s, the Mar-Keys, and Otis [Redding]. I don’t know that we had more than those in the category of the top stars.”

Moore himself described the situation hilariously in his acceptance speech for Sam & Dave’s induction into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame in October 2015. “When Dave and I first came to Memphis,” Moore recalled, “the first person I saw was David Porter. He had on a small hat, a big sweater, and his pants looked like pedal pushers. Water came into my eyes.” Moore paused for laughter with impeccable comic timing. “Then it got worse: I saw Isaac. Isaac had on a green shirt with a low-cut neck, like that, a white belt, chartreuse pants, pink socks, and white shoes. I started crying harder. I wanted to go home.”

There must have been more than a little truth to that, for, as Moore went on to explain, “I had in mind to sing like Jackie Wilson, James Brown, Wilson Pickett … but then they introduced us to these two guys and we went inside and they introduced us to the songs. And they didn’t sound nothing like Jackie Wilson and all these people! And then I turned to Dave … and he was trying to get a phone number to get to the airport.

“Being the new kids on the block, we had nothing to say. So we had to go on in there.”

In fact, they were walking into the Stax brain trust, which had always dared to be different. When Sam & Dave’s pre-Stax singles tried to emulate the more polished soul of Wilson or Sam Cooke, albeit without their orchestral flourishes, the results came off as rather corny. Now it was 1965, and pop music was getting edgier, from Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” to the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Even James Brown, whose biggest hits had been ballads like “Try Me,” was cooking up material like “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.”

Dream Team

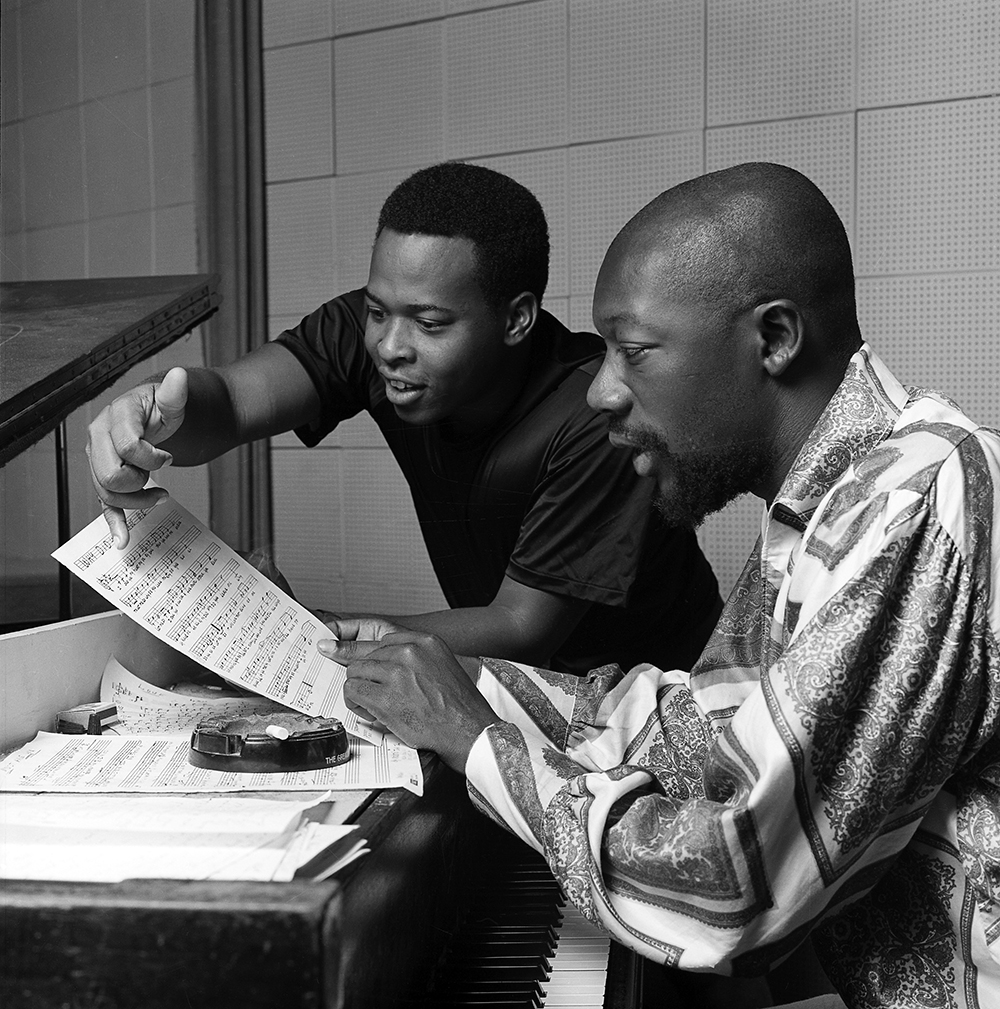

David Porter, who saw their potential early on, inched them toward a rawer take on soul music when he penned the shuffling, feel-good “A Place Nobody Can Find” for them, though the B-side, written by Porter and Steve Cropper, was a more tender ballad, with sassy horns thrown in for good measure. Unlike their later hits, Prater was given the lead vocal, though Moore’s upper register parts hinted at the harmonies that were to come. It wasn’t until their next single that Porter and Hayes teamed up to produce the duo, and their nascent songwriting partnership blossomed. And they gelled not only in the substance of the songs, with Porter crafting lyrics for Hayes’ music, but in the strategy they mapped out for the two new kids on the block.

Reflecting on that strategy today, Porter says that Sam & Dave “didn’t have a concept as far as the artistic direction that they needed to go. That’s why Jerry Wexler, the president of Atlantic Records, brought them to Memphis, in hopes of finding whatever that was — he didn’t know what it was. But we had our concept of what we wanted to do, and that was to bring it out of the church, the spirituality out of the church, and have the music emphasize what we called the low end of it, the bass, drums, and guitar, and the underlying chord progressions in the low end, paired with the gospel persona of it, the spirituality of the church.”

And yet, as with Ray Charles and so much of the finest soul music, the gospel underpinnings supported very secular, worldly sentiments. Lyrically, Porter paired the world of the bluesman with the spirit of church. And that came as a shock to the singers, who had both grown up singing in church choirs.

“David Porter and Sam could clash,” Parker recalls, “but it wasn’t hostile, and it didn’t last but a few minutes. It was like they were sparring, you know? Of course, Isaac’s thing was the keyboard, he was the melody man, and Porter was the lyricist. And sometimes Porter had to stop and help both of the guys understand what he meant when he wrote, ‘Coming to you on a dusty road.’ You know what I’m saying? Because this was not Sam & Dave’s environment. This was David Porter’s environment from the area around Millington, Tennessee.”

And so a great foursome was born, beginning with the single “I Take What I Want,” which, as Bowman notes, “was to provide the model for the majority of Sam & Dave’s Stax 45s.” By the time “Hold On, I’m Comin’” dropped in March of 1966, topping the R&B charts and reaching number 21 on the pop charts, that model was locked in. After crafting a song and a sound, Porter and Hayes would only need to give the duo a brief rundown before they got it. Porter can still picture it today: “I’m standing there with them, and I’m looking at them as I give them the lyric sheet. We go through the melody at the piano, and then by the time they get on the microphone, they go into another world. They made it their own, and that’s when you know you’ve got something special.”

And so, even if “Sam was the dominant one,” as Parker recalls, and more prone to pushback, both Sam and Dave were consummate professionals. “We had to go on in there,” as Moore recalled, and they did.

Porter says, “There never was a comment like, ‘Well, I don’t want to do that song. I don’t like that song.’ Because we produced the albums, even when we were doing a song by some other writer, and on occasion we would do that, they still didn’t object. They would bring their own spirit and commitment to wanting to make it as good as it could possibly be. And they did that.”

The Key to the Speedboat

The foursome’s recipe for success not only gave Sam & Dave’s career a boost; it solidified Stax’s standing as a label. As Robert Gordon writes in Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, “their album Hold On, I’m Comin’ proved to be the breakthrough for Stax’s album sales. In all the company’s years through 1965, they’d released only eight albums. … In 1966 alone they released eleven albums and Sam & Dave’s Hold On went to number one on the R&B album sales chart. Albums were good business.”

Parker likens it to the fledgling label acquiring a sleek new machine. “They reminded me of a speedboat,” she says. “A boat that nobody was 100 percent familiar with because they were not on the water in the speedboat every day. They had to figure out a lot of things mechanically, and they had to become acquainted with each other. And I’m talking about Sam and Dave and David and Isaac. Once Sam and Dave found their groove with David and Isaac, it was like they had found the key to speedboat. They then began to realize that they had more going for them with their new producers than they’d ever imagined.”

If the speedboat was designed by the producers, Porter makes it clear that Sam & Dave supplied the spark of ignition. “You, as a creator, can create something that you know is strong and good, but when you have an artist that’s able to create their own individuality through the spirit of what you’ve done, then you’ve got something special. That’s the thing that made Sam Moore such a special talent, as well as Dave: They would go into the ownership of the message. I would tell them where the vibe was, and they would have to live the spirit of the message. That’s where true artistry comes in. And the more songs we wrote for them, the more comfortable they would get into doing it.”

Or, as Porter wrote on social media after Moore’s death, Sam & Dave “were always filled with passion, purity, individuality, and believability, grounded in soul.”

The road grew dustier and rockier as the years rolled on, with Atlantic claiming ownership of all Stax masters prior to 1968, and taking Sam & Dave away from Memphis. The duo never reached the heights of their Stax records again, and split apart as Moore struggled with addiction through the ’70s. Yet, with the help of his wife Joyce MacRae, whom he wed in 1982 and who now survives him, he kicked drugs (coming to support several GOP candidates along the way) and revived his career without Prater (who died in a car crash in 1988).

By the time he spoke to the Memphis Music Hall of Fame 10 years ago, Sam Moore had fully embraced his Stax past. “Coming from a humble beginning, with no formal training in singing or anything, we were just two guys who got out there and took the church with us, like Al Green did. … I’m going to say this to you: Thank you Memphis people, the band, the friends that Dave and I met all those years. …They believed in us. They stuck with us. Every record company that we had been with just didn’t know what to do with us. Sixty years later, I’ve been doing this. I’m blessed.”

Sam Moore knew he’d helped build something for the ages. As David Porter reflects now, “The music that was done by the four of us together will live on forever. There’s no doubt in my mind.”

Shawn M. Carter

Shawn M. Carter  courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor  courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor  Shawn M. Carter

Shawn M. Carter  courtesy Ditto Taylor

courtesy Ditto Taylor

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd