‘Three Legged Horse’ by Fletcher Golden

Fletcher Golden’s first big adventure was when he ran away from home in the third grade.

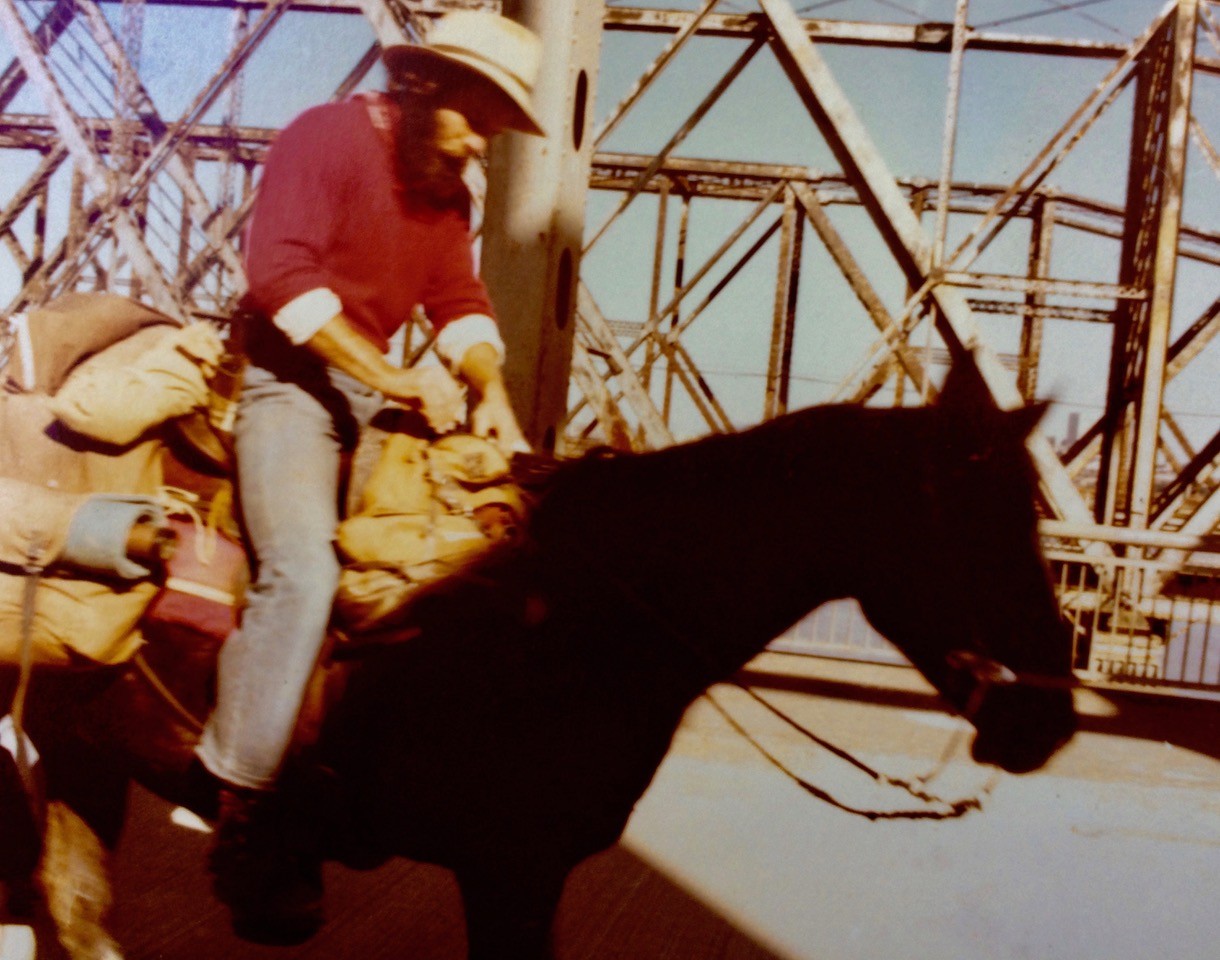

He was caught smoking at school. “I got with another boy who also was accused of smoking and we got on the bus and went Downtown and walked across the Memphis/Arkansas bridge,” Golden says. “We got caught at that weigh station. My dad came and got us.”

Golden got “a whipping” for that adventure. His second big adventure was when he was 30 years old and he rode a horse 2,500 miles from California to Memphis.

His love affair with horses can be seen in his new exhibit, “The Poetry of Horses,” at Palladio Antiques. The exhibit features 14 horse-inspired sculptures. “A lot of them are steel-framed armatures and with partial armatures exposed with some plaster collage. They represent maybe the horse’s main torso and have stick legs. Pecan branches from pecan trees. I live in Midtown. I’ve got all these pecan trees in my backyard.”

Fletcher Golden

Also in the show are watercolor horses by Golden’s wife, Jeanne Seagle.

A native Memphian, Golden, 72, who is one of eight children, was ordained an “adventurer” when a series of photographs of him appeared in 1951 in The Commercial Appeal. Once again, he was caught by his dad, but this time without any repercussions. Photos begin showing Golden climbing the stairs of the slide at Maywood Beach and end with his father catching him when he hits the water. “The headline referred to him ‘Three Year Old Adventurer.’”

Majoring in marketing at Memphis State University, Golden was drafted during the Vietnam crisis, but he didn’t go overseas. “I had a sense to see the world,” he says. But he ended up “babysitting AWOL kids” about his age as the stockade guard at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri.

He went back to MSU after he returned to Memphis, but he realized he wasn’t ready for school. He got a job working at TGI Friday’s franchises around the country. While working at one of them in Shreveport, Golden met a young woman.

Golden followed her to California, where she was going to school. He got a job and took a finance course, but then he decided to quit the job and the finance course. And he thought, “You’ve got to hurry up and take a vacation here. See some of this California stuff.”

He thought about biking, hiking, or motorcycling. “Then I came up with the idea of the horse. That’s how the horse trip came about. That way I could see the country. I could meet the people on the back roads. People that lived beyond the asphalt interstates or the highways. That was part of my dream.

“When I thought about where to go, I thought, ‘Why not go to Memphis? You know people there. It’s not just going to Memphis. It’s what you see in between.’”

And he thought, “If you don’t do it now, you’re dead.”

“You outgrow the early weaning of Roy Rodgers, the plastic pistols, and the fast draw in front of the mirror. It’s still in you, but there’s no access to demonstrate it. So, I think maybe that horse trip alone did that. Knowing I’d chicken out if I didn’t hurry up.”

Golden only had slight horse experience. “My grandad had a farm in Raleigh off of James Road. So, growing up, my family would go out to his farm. About 25 acres. And he had a palomino, so I had exposure at his farm.”

After he figured out his destination, Golden’s next step was to find a horse. “I looked in the yellow pages. And outside of Berkeley — Danville, California — there was a horse operation.”

The man at the ranch showed him several horses after Golden told him his plan. “He let me try the Tennessee Walker. I put her through her paces. I galloped her and saw how smooth she was. So I was committed to her.”

Golden sold a 1958 TR3 convertible he was restoring and a motorcycle and bought the horse. “I was thinking about that convertible to drive down Highway One to Pebble Beach and go on to Carmel and play golf, scuba dive, and smoke dope.”

But he sold the car and bought the horse along with a saddle and saddle bags. He named the horse “Brooks” after a family friend.

Golden, who used U.S. Geological Survey maps, went East from the beautiful, lush area of the Sierra Nevada on to the high plateau desert. “I was told by people, ‘Don’t even think about going South. Stay on this high plateau area for the horse’s survival. You’ll die.’”

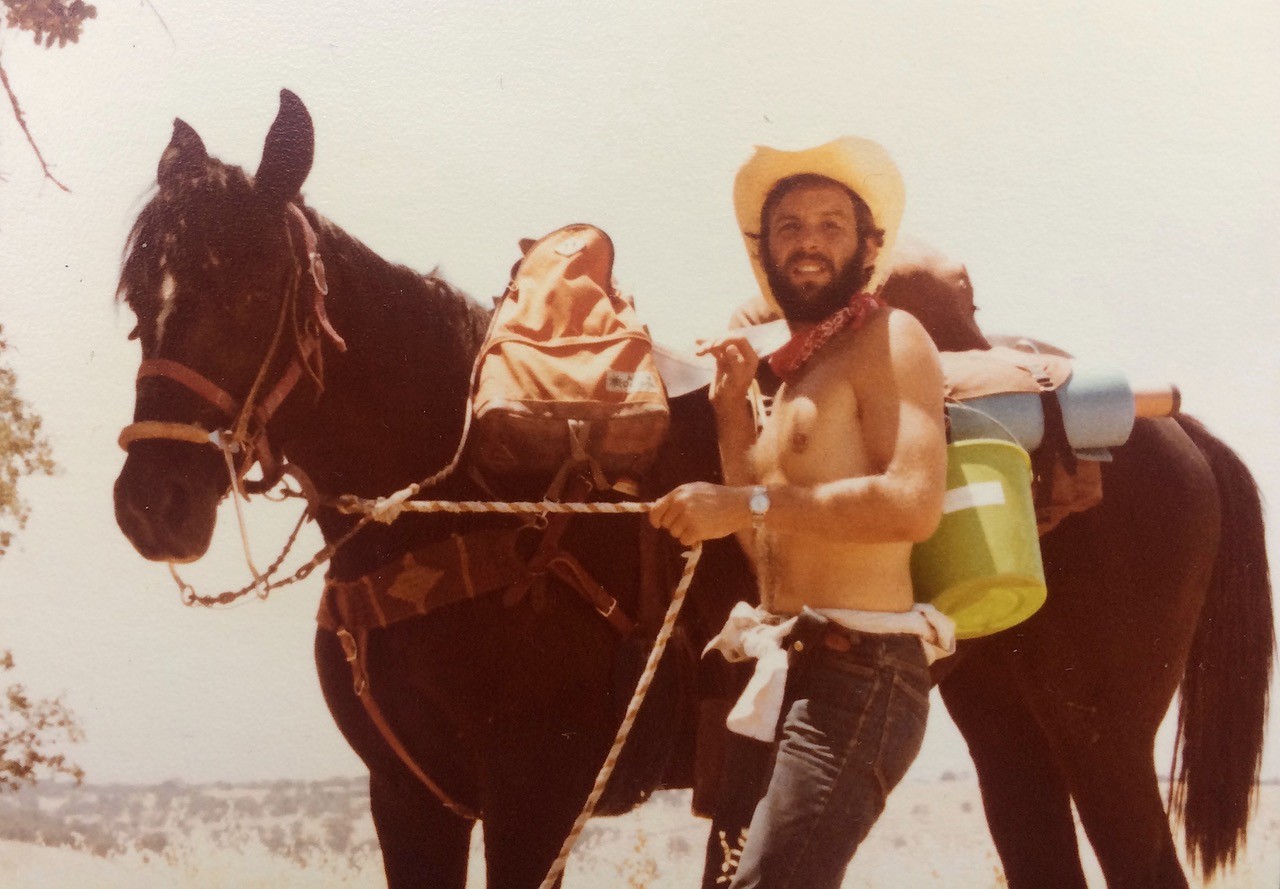

Fletcher Golden and Brooks

The maps included notations of where ranches were located. Golden stopped at the ones that looked the friendliest and he offered to mend fences or do other work in exchange for grain, hay, and water for his horse. “They would invite me in and tell me their life story, and I was a good listener.”

He learned the country motto, “Pass it on.”

“They were super hospitable to me and all they wanted was for me to be generous to someone else.”

Golden went through a daily routine. “Every day I would walk about three miles holding the reins. And after three miles I’d get tired of walking and get up on Brooks and ride another three miles until I got tired of doing that. I’d just do that all day long.”

There were thrilling moments during his trip. Like the time he rode saddle broncs in rodeos in Utah. “I flew off in maybe two seconds. In the second rodeo, I lasted maybe four. They were really incredible experiences of disorientation: looking at the ground, at the sky, and then flying. And then you check your body out: ‘Oh, God. Everything is there.’”

There were idyllic moments. “I got to swim with my horse in a little pond area in the desert.”

And he met people he still keeps up with, including a guy he ran across in Lenopaw, Oklahoma. “I was going down the road and this guy saw Brooks was limping a little bit. The guy was about my age. He invited me to rest my horse. They had a cattle operation.”

He asked Golden “if he smoked dope” and offered him a joint. “He was such a wily character. I was enamored by this guy. Willie Howell. I still call him up every once in a while.”

Golden managed to get by, but, he says, “I was with the horse. And I had some credibility by getting that far. Whatever I needed as far as re-shoeing my horse or food or whatever, it was provided.”

Before the trip, Golden “had that desire to be somebody without doing the work. Just be somebody.”

But, he says, “I was forced to be more in the now. It was the first time in my life where I had to care for a living being. I had to watch that horse every second. Make sure she didn’t hurt herself in a gopher hole, glass. I had to put liniment on her legs all the time.”

Golden, who began his trip June 5, 1979, made it to Memphis on December 5, 1979. His appearance changed during the six-month trip. “I was able to grow my beard. I had a little bitty cute beard when I started, like maybe an inch and a half. And I didn’t touch anything on the whole six months. When I got to Memphis, I had a really big beard, nice strong wavy hair.”

Fletcher Golden and Brooks

He soon moved back to California, where he ended up living in a trailer on five acres with Brooks in the Berkeley Hills. “Then one day Brooks went colic. I called the local vet. He said, ‘Take her up to the University of California Davis.’’’

Golden and the vet got Brooks in a trailer and took her to the veterinarian center at the university, where she was put in a paddock. “She’s lying down. They put a tube in her nose. It goes down into her stomach. I was there with her for about two days. And after two days I told them, ‘I’m going to go get something to eat.’ And when I came back they said, ‘Well, she died while you were gone.’

“I go in there and put her head in my hand kind of thing. I cried. I usually don’t cry over animals. But this thing was so big. It really touched me.”

They loaded Brooks into Golden’s truck. He met two rangers who told him to follow them to Briones Regional Park. “They take me down to this meadow area.”

He and the rangers buried Brooks under a Mayberry tree.

While at UC Davis, Golden asked for his horse’s heart, which they removed for the autopsy. “If you’ve ever looked at a horse’s heart, it’s like looking at a gigantic rugby football — just smooth, and no contours. Not like a human heart. It’s just a big muscle. White muscle.”

He asked a friend’s girlfriend to go with him to bury the heart in the Pacific Ocean. “She and I climbed up this little rocky path-like cliff looking down at the ocean coming into the bay. And I had the heart in Brooks’s halter. She read a poem, ‘Remembrance,’ as I did a Grecian discus throw to get it way out so it wouldn’t hit the rocks down below. When it hit the water we saw seals go up and dive back down, assuming they were going to eat that heart. Then I looked to the west and the wind was coming in like a constant breeze.

“It was the best funeral I’ve ever been to.”

Golden created his first horse sculpture after he took a job in 1995 at the Maria Montessori School in Harbor Town. “I kept that job for 20 years. I was the outdoor guide at Maria Montessori. So, I taught kayaking, how to use tools, nature appreciation with nature walks.”

He and the students created sculptures for the school’s fundraisers. “The kids and I would go and collect driftwood on the river at Harbor Town and bring it back and there we would come up with a sculpture for our silent auction.”

The pieces were “just abstract. They weren’t anything figurative or realistic. Just form and color. And really jazzy. The driftwood was really talking.”

In 2009, Golden, then 61, took a return trip by car from Memphis to California, using the same maps and visiting as many of the ranches as he could from his original trip with Brooks. “I had my names and addresses of people that helped me.”

And, he says, “They either remembered me and the horse or they didn’t remember me but they remembered the horse.”

After that trip, Golden was inspired to make a horse sculpture with the students for the silent auction. “I wanted to do the homage to the horse. We go back with Radio Flyer wagons to collect wood. I saw one big old log. I thought, ’This might make the face of a horse.’ A lot of the kids thought it looked more like a pig than a horse. We whittled away enough of the rotten pieces that it was possible as a horse’s head.”

They used “pretty good sized” crepe myrtle limbs for the body.

Golden had Friday off, so he finished the piece himself. “I created a big temporary crane to hoist the thing up at the event. It was a Saturday night. Maybe five minutes into the event, six o’clock at night, I finished.”

The horse sold for $1,800.

Memphis abstract artist Jeri Ledbetter fell in love with the horse and asked Golden to make one for her. He told her, “If you really like it, it will be $3,000. If you kind of like it, it will be $2,500. And if you don’t really like it, but you’ll take it, it will be $2,000. But you’ll have to wait because I’ll have to build a workshop and collect tools.”

Golden hired a friend to sing cowboy songs at the unveiling of the horse statue in 2013 at Ledbetter’s home.The three-quarter size horse had one of its three legs, which were made of steel rods, stuck into a limestone base. The leg came up to the horse’s carriage, which was made of car springs and driftwood. Two more legs stuck out toward the viewer. “I had to make a head out of three-eighths steel rod. And I attached little pieces of driftwood that gives a balance of positive and negative space.”

In 2013, Golden exhibited seven of his horses at L Ross Gallery. “Some were plaster with cement coloring agent in the plaster. All of these were with steel frames. Every one of them was a take off of the elements of a horse or the impression, but none of them were really staying close to the realism of horses.”

His current show ranges from his nine-and-a-half-foot-tall “Calligraphy Horse” made of wood and steel to a little seahorse made out of seashells. “Some really good big ones and some small ones.”

He also included 16 steel silhouette figures showing different movements of the horse based on Eadweard Muybridge’s “The Horse in Motion” photographs, and three glazed ceramic and steel horses that he calls ‘Noguchi’s Horses’ based on the “flavor” of sculptures by Isamu Noguchi, who used various materials in his work.

‘Shadow Horses’ by Fletcher Golden

To date, Golden has made about 40 horse sculptures, most of which are in private collections. But, he says, “I’ve not nearly scratched the surface of interpreting these horses in ways that portray the relationship various people have had with horses. And the mystique of being a child and learning how to relate and ride and work with the horse.”

Golden loves “the idea of the horse. These guys let you get on them and ride them. That’s fantastic. To get up and all of a sudden you’re looking out and your eyes are about nine feet off the ground. You’ve got the rhythm of the horse, the snorts it makes, the great, wonderful smell of the horse. It has these wonderful neck muscles.”

Was Brooks and his trip with her the inspiration for his horse sculptures? “Absolutely.”

And, Golden says, “That was the biggest experience of my life. I got to keep an animal alive for six months. Putting liniment on her legs every day, you feel her fetlocks, how they line up. And just getting local opinions from people. That was their business. Taking care of their animals, their land, their machines, and their family. We were able to share.”

“The Poetry of Horses” is on view through November 6th at Palladio Antiques at 2169 Central Avenue; (901) 276-3808

Fletcher Golden and Brooks