In their current exhibition, “Cross Pollination,” mother/daughter duo Paula Temple and Ariel Baron-Robbins have filled Harrington Brown Gallery with watercolors, oils on canvas, collages, videos, and large drawings of nudes that take figure studies to the level of fine art. Two signature pieces — Temple’s The Last of the Honeysuckle and Baron-Robbins’ Kudzu — are good indices for the level of skill at which these two artists are operating.

A full-figured woman in a frayed robe sits in an overstuffed chair in The Last of the Honeysuckle. This watercolor of fading Southern gentility is made particularly haunting by Temple’s accomplished handling of lamplight, which transforms the room’s floral wallpaper into a luminous garden and the woman’s face into a milk-white mask that captures, in equal measure, unflappable Southern matriarchy, the feminine mystique, and the nearly impenetrable nature of the human psyche.

By weaving yellow and gold honeysuckles into the fabric of a comfortable old robe, Temple adds a touch of humor and tops off a painting that’s as intricately patterned as one of Vuillard’s or Bonnard’s interiors. In spite of Honeysuckle‘s complex design, Temple’s colors and lines are laid down with assurance, and this painting is remarkably crisp, clear, and clean.

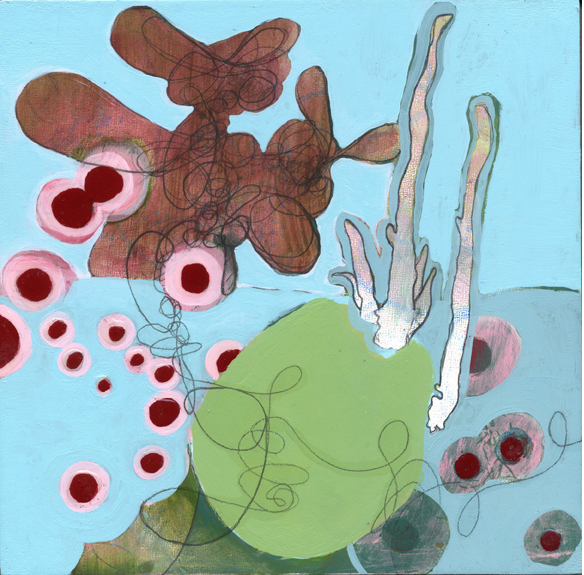

For collage paintings like Kudzu, Baron-Robbins draws organic and geometric motifs on large sheets of paper, shapes and reshapes her surfaces with torn pieces of discarded drawings, and then paints the layers with a mix of acrylic, graphite, and gouache. Rather than feeling stultified or impenetrable, this compellingly visceral painting, with its cool-gray shadows and pitch-black passages, is enticing. What would it be like to sink our hands into its dank surface, to stroke the stonework that appears to be eroding back into an unpruned, centuries-old garden?

Through August 3rd

“A Modernist Ouroboros” at Askew Nixon Ferguson Architects features the works of Adam Geary and Anthony Lee.

Geary paints scenes of New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Having attended school, lived, and/or painted in these locales, Geary knows these world-class cities. He also knows how the noonday sun turns the tallest skyscraper in New York’s Union Station into a white monolith; he remembers the cracked window and peeling sill on the backside of the apartment complex where he lived in San Francisco; he still feels the pulse of these super-charged cities.

Without creating a hodgepodge of styles, Geary skillfully blends architectural details with expressive lines, nuanced color fields, and evocative shadows to capture the soul of a city as well as its shape. His most haunting work, Nob Hill, combines abstracted architecture (Diebenkorn and Thiebaud come to mind) with Rorschach inkblots. Dark washes of color flow out of the basements of tall lean hotels and skyscrapers, snake across a street, and touch the curb on the other side. These are late-afternoon shadows — night is approaching, the city spilling some of its secrets, taking on a more sensual, slightly ominous persona.

Although the titles of Anthony Lee’s paintings feel, at first, enigmatic and possibly inscrutable, Lee’s use of an ancient alphabet, the Runes, as names for his abstractions proves surprisingly apropos. Like Lee’s artwork, the characters of the Runic alphabet are geometric shapes whose meanings (unity, transcendence, light, flow) beautifully evoke the attributes of art as well as of life. High-key colors (cylindrical spring greens and white orbs back-dropped by burnt siennas) make this body of work feel even more emotive and alive.

Described by the artist as “early video games, vintage cyberspace, and environments,” these finely tuned abstractions feel like moments of equipoise — pieces of the puzzle slipping into place, the mother board about to switch on, Pac-Man at the ready to race across a video screen eating dots and avoiding ghosts.

Through July 23rd

In March 2010, Rhodes College junior Justin Deere bought 80 disposable Kodaks with grant money he received from the Center for Outreach in the Development of the Arts (CODA).

A team of students gave the cameras to volunteers and staff members running soup kitchens and other nonprofits as well as to the Memphians these agencies serve. They asked the recipients to tell their story through photographs and to share their work in “Unsheltered Unseen.”

Some of the most provocative and poignant photographs produced by this project, all untitled and currently on view at Jack Robinson Gallery, include Shun Maxwell’s image of a man sleeping outdoors, in broad daylight, on bare cement. In another candid work by Maxwell, a group of comrades sit on a discarded couch on top of rubble next to barbed wire.

In an image by Terrie Cooper, a big black dog lies on a man’s lap in a brightly lit living room. Both creatures look grateful for a warm, safe, dry place in which to doze. Cro Wilhite captures another attempt to stay warm and dry in her unsettling portrait of a woman wrapped in a large green blanket, squatting on a dirty cement platform next to a potted plant beneath a handicapped parking sign.

In one of the show’s most playful and empowering works, Reginald D. McGregor uses his camera to record a man with “wheels,” warm winter clothing, and a big, easy smile hoisting his bicycle high in the air. In another image, by an unknown photographer, large white letters spelling out the word “Heal” are back-dropped by an artificial blue sky, which, in turn, is back-dropped by an unsettlingly real, nearly pitch-black night sky. The billboard’s small print reveals that this is an advertisement for a cancer institute. “Heal,” the billboard proclaims … in spite of life’s vagaries, calamities, diseases, and aging processes that, ultimately, claim us all.

The candid details and private moments of courage and pain in many of the photographs could only have been captured by someone who is homeless (or has experienced homelessness at some point in his/her life).

These works, in particular, affirm the human spirit’s resiliency, its ability to find hope and camaraderie in the most difficult of circumstances, and indeed its capacity to heal.

All money generated by the sale of prints of photographs in the show goes to nonprofit organizations designated by the artists.