It is often said that this or that politician is unique, one of a kind, like nobody else. In most cases, this is so much hooey. Scratch most of the so-called mavericks and you will find the same old-same old political template, embedded with a given set of issues or loyalties or a party platform.

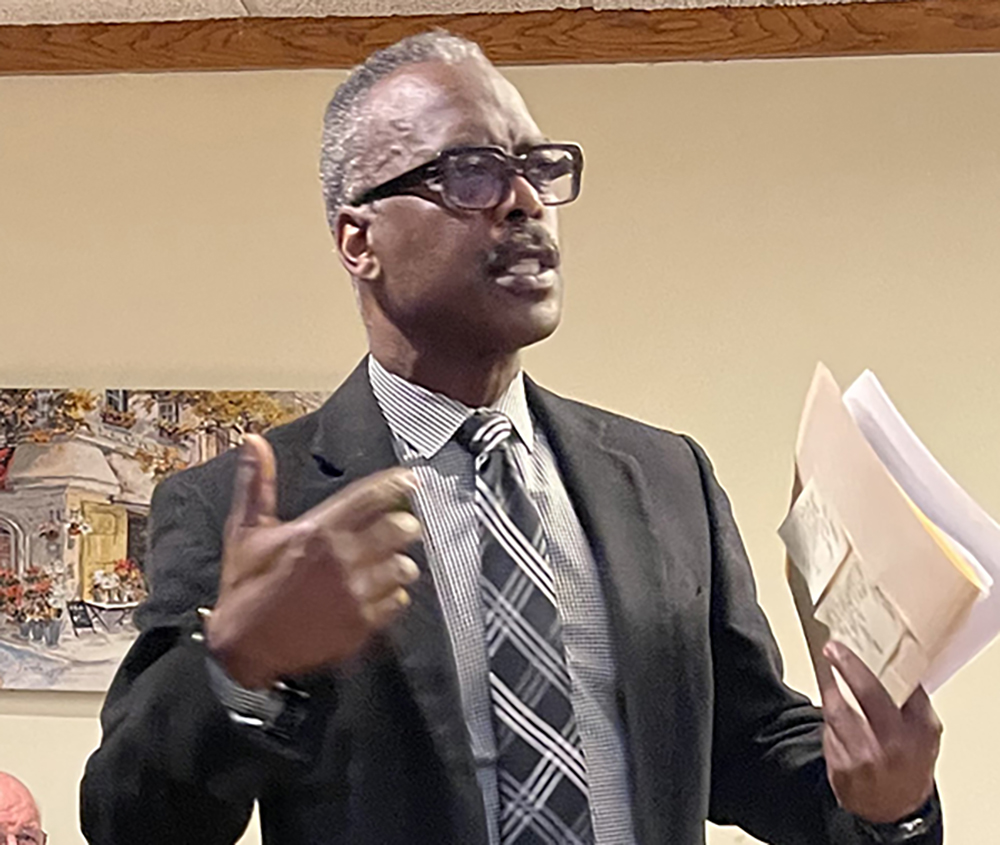

James Harvey, the new chairman of the Shelby County Commission, believes he’s different, and he may be.

Among other things, Harvey is unique (there’s that word again) among public officials in that, time after countless time in commission debate, he has begun a speech apparently underwriting one point of view as solidly and sincerely as can be, and, several rambling minutes later, has ended up espousing the other side of the case.

It is as if he is thinking out loud and manages to change his mind by listening to his own, often apparently disjointed, stream of consciousness.

Harvey acknowledges that he seems to be doing this, but he says it’s so much smoke and mirrors. “Contrary to what the media says, I don’t waver. The media says that, because they can’t keep up with me. And they can’t keep up with me, because those are my intentions. I don’t like people to keep up with me. I like to get my point across.”

So he’s not really thinking out loud, as in fact his colleagues, not just the media, often are convinced. “It’s just my style, because I plan to drag you along. Every time an issue comes up, I know where I am. I leave room for adjustment if need be, but I generally know where I am.”

Whatever.

In any case, Harvey caused a serious kerfuffle recently by reversing course on the question of the Shelby County tax rate. Having voted with his fellow Democrats on both the budget increase and tax-rate increase desired by county mayor Mark Luttrell back in June, Harvey then did a turnabout and voted with the Republicans to reject the tax-rate increase, from $4.02 to $4.38, on the crucial third vote in July.

Here was the moment of transition, or of “adjustment,” in a longish Harvey speech as the commission prepared for the key vote:

“I’m not sure where I am with the tax rate. … I don’t want to vote for the tax rate, but I don’t want services cut or employees laid off. … If I had to vote today, I would vote not for the tax rate, to be honest with you. … I don’t think line-item services have been reduced. … We ought to be able to see some other reductions. …

“The county commission needs a budget analyst. … We can’t watch all the shenanigans of the departments. … I’m in a hell of a position, and that’s very uncomfortable for me. … I don’t know where I am, but I’m still pondering. At this point, I’m a little fuzzy.”

When Harvey was through, GOP commissioner Chris Thomas, an opponent of the Luttrell request, observed, “I should have gone to get a haircut during all of that.”

In fairness, a fairly consistent point of view can be parsed amid this foreshadowing verbiage. As Harvey elaborated in an interview this week: “My argument has always been about government waste. I think we’ve got too much money.” His original inclination was for a tax increase, but “only for the sake of the schools.” And that, as he noted, equaled to about $10 million. “It didn’t make sense to increase everybody’s costs forever just to amass $10 million. It was very regressive — all those omnibus interests that were included in that resolution, camouflaged by funding the schools!”

So he had gone along with the Luttrell request and with his fellow Democrats on the first reading only: “I tried to toe the line, but my heart was never there. And, thereafter, I just couldn’t do it. I didn’t switch back and forth.”

The tax rate would eventually be passed on a second try at a third reading, but Harvey had meanwhile cast his lot with a hard core of suburban Republicans who wanted no part of it.

Between his aye vote on the first reading and his nay vote on third reading of the tax-rate ordinance, and not one but two or three speeches outlining his revised attitude toward the issue, there was a chairmanship election. Harvey, a true dark horse, had defeated both incumbent chairman Mike Ritz, a moderate Republican who was often at the head of a basically Democratic coalition, and Democrat Steve Mulroy.

Early in the voting, most members of the commission’s suburban hard core had given their votes to Mulroy. Aggrieved by what they regarded as Ritz’s ongoing political apostasy, they had settled on the liberal Mulroy as part of an “anybody but Ritz” strategy.

But as a deadlock between the two main contenders wore on, it finally dawned on these conservatives that Harvey was not only not Ritz but, unlike Mulroy, had come to the same conclusions as they had on the tax-rate question.

And so, on the basis of some last-minute vote-switching, Harvey won commission chair, not without suspicion among some of his Democratic colleagues that he had vote-traded his way into the chairmanship.

…

A biographical digression: Harvey has often, in debate, cast himself as a businessman, complete with the fiscally conservative views that come with that description.

And the word “businessman” seems to be a fair description of what Harvey is. As he cataloged the elements of his curriculum vitae in a conversation with the Flyer this week, the 51-year-old Harvey said he has owned a security service (“Guards Unlimited”), a mortgage company, a tax service, and various real estate investments, and he has had jobs with any number of legitimate corporations — for example, the Bank of America, which employed him to review loans and foreclosures in the wake of the bursting of the housing bubble that came near to wrecking the American economy in 2007-2008.

That particular catastrophe also caused Harvey to close down his mortgage business, and he boasts, “I had no debt; I never filed bankruptcy, never foreclosed on a property, never had a business loan in my life. I did everything with my own money.”

Nevertheless, he had a tight moment or two in the wake of the recent recession, and the BOA job was something of a makeshift solution that kept him absent from much commission business and numerous meetings, especially in 2011. Eventually, earlier this year, he landed a position as a vice president of Memphis-based Tri-State Bank, and it was that serendipity that allowed him to turn his attention back to politics and government and, ultimately, to the idea of being chairman.

As Harvey tells it, his personal story sounds like an installment of the Horatio Alger saga. He was one of nine children raised on Memphis’ south side, never knowing his father. For roughly 10 years of his growing up, he had a stepfather, and “that’s where ‘Harvey’ came from.”

For all the family’s privations, his homemaker mother made sure that Harvey and all his siblings got college degrees. His own itinerary took him through South Side High School, Southwest Community College, Memphis State University, and the course-work of the University of Phoenix, an online institution, which awarded him a B.S. in business management.

“I was the only one who went into the military, the Army. I was the only one who started a business. I was the one that always took the risk. I was the seventh child,” Harvey says.

He has a 25-year-old son named James Harvey Jr., whom he also describes as a “businessman” and with whom, in fact, he is engaged in several investments and enterprises. As commission chairman, he has dibs on a largish office in a back corner of the commission’s office suite and two pictures of himself with his son — one a cutout poster of the two that promotes a brief career as a motivational speaker.

There is a tenderness in the cutout that is in clear contrast to the admittedly regretful way he speaks of his two marriages, both of which ended in divorce. “I was hot-headed. If it wasn’t my way, I’d just pay to get rid of you,” he says bluntly.

Prior to his political career, most Memphians who got to know Harvey outside his business circles encountered him a couple of decades back when he became a featured player in the annual Gridiron shows presided over by the late Terry Keeter and Larry Williams. These were musical revues that satirized the world of local government and politics and for some time used to draw huge crowds.

Harvey’s introduction to public life came from his burlesques of local African-American eminences. Harold and John Ford, Willie Herenton, Michael Hooks, or Rickey Peete: Harvey was cast as whoever was black and was being sent up in skit.

“I couldn’t dance, but I could sing,” declared Harvey during the Flyer interview, and he demonstrated the latter prowess before a small group of onlookers, doing several impromptu lines from the Showboat classic “Ol’ Man River” in what he called a “heavy baritone,” actually a deep basso.

After the retirement of the late James Hyter from doing riverside versions of the song as the finale of the annual Sunset Symphony extravaganzas, Harvey wanted to be Hyter’s successor but couldn’t sell the idea to the Memphis in May management. He saw the issue as having to do with his lack of clout at that time. “I’m not in the clique, I won’t be in the clique. There wouldn’t have been a debt to repay,” he says.

Partly, he saw politics as a way to remedy that. He saw it as a way of “giving back.” His first race, with support from outside the usual circuits, was in a special Democratic primary election for the state Senate in 2005. He finished second, ahead of Michael Hooks and behind Kathryn Bowers.

Harvey tried again in 2006, running for the District 3, Position 1 seat on the commission and winning. He was reelected in 2010, though he speaks edgily of the support he says his primary opponent in that race, James Catchings, got from “some of my colleagues [who] were very hopeful that I would be defeated.”

As a commission member, Harvey has always been sort of an outlier, and he likes it like that. His idiosyncratic verbal adventures, his sampling out loud of contrasting positions, his standing apart from factions — all that has characterized his tenure.

…

Still, Harvey has been a Democrat and, up until recently, a member of the majority that bitter online commenters from the suburbs have taken to shorthanding as “the CC8” in the 8-to-5 votes that have pitted the county commission as a litigant against municipal-school efforts in the county’s six outlying municipalities — Germantown, Collierville, Bartlett, Lakeland, Arlington, and Millington.

All that may change now. Asked if he would continue to back the position of the the commission majority on school issues, Harvey answered, “Probably not. I want the lawsuit to go away. I want a resolution among all the suburban cities, based on agreement realized. Once we get out of the middle of that, the school issue will probably form itself the way it’ll end up anyway.”

If that sounds oblique, Harvey can cite particulars. The commission majority — the body’s seven Democrats plus former chairman Ritz — has consistently taken the position that the proposed new suburban school systems should not acquire existing school buildings, technically the property of the Unified School System’s board, for anything less than “fair market value.”

Harvey now sees it otherwise. “Honestly, I think we should give them the schools.” Provided, he adds, that the suburbs do not use their educational independence to reinstate anything like segregation.

The new chairman bristles at any suggestion that his current positions have anything to do with political quid pro quos. He was censured recently by the executive committee of the Shelby County Democratic Party for his committee assignments, notably the substitution of Republican fiscal conservative Heidi Shafer for Democrat Melvin Burgess, the Unified School System’s audit director, as budget chairman.

“I like Burgess, think he’s a sharp guy, but I think it was a conflict of interest for him to work with the budget for the schools when he’s working on the [county] budget.” He brushes off the suggestion that he has adopted the position of firebrand Terry Roland, the Millington Republican who has brought conflict-of-interest charges against both Burgess and Sidney Chism (the latter stemming from Chism’s ownership of a day-care center that received some Head Start wraparound funds).

As for his appointments at large, Harvey muses frankly, “They may say that I cut a deal with the Republicans after they elected me. I don’t care what they think. I believe in rewarding people that believe in standing on principle.”

The state Democratic Party’s executive committee recently deferred action on underwriting the local party’s censure of Harvey, basically blowing it off. That may owe something to Harvey’s making a point of contacting state party chairman Roy Herron and members of the state committee to convey his views about the matter.

But the whole party thing is now a sore point with Harvey. Term-limited on the commission, he has ambitions to run for something else — “city or county mayor or Congress.” But his thinking about the party label is now iffy. “You’ve got a small group of people that have ruined the [Democratic] party. I don’t like bullshit. I’ll run as a Democrat unless they kick me out, and [then] I’ll run as a Republican.”

Calling himself “a Democrat at heart,” Harvey nevertheless underscores the fact that he has options. As for the local Democrats’ attempt to get him censured at the state level, he says, “Woe to the party if they had succeeded. I would have been a tyrant on their asses. If I could change parties and hold my support I would change tomorrow. I like the Democratic Party. I am a Democrat. But if they get to doing some funny business, I’ve got a party to go to.”

That’s a shot across the bow. While making no secret of his political ambitions, Harvey is prepared, he says, to be fatalistic. “I’m one of those guys they can’t push around. If I was kicked out of politics today, I’d just say f–k it and keep going.”

…

But the new commission chairman has a vision. Presiding at his first commission meeting last week, he began proceedings by reading aloud a manifesto, here reproduced in its entirety:

“To the commissioners, administration, staff, constituents, family, friends, and guests:

Thank you for being a part of today’s political and business process. As the new chairman, I would request that you conduct a behavior of orderliness relative to your participation, perceptions, persuasions, and response.

A chairman is one who manages and provides leadership to the body of this board on behalf of our constituents.

I believe in leadership at any risk. I am first man, father, community activist, business leader, then political leader.

Leadership is the capacity to care, and, in caring, to liberate the ideas, energy, and capacities of others.

Leadership is the integration of heart, head, and soul.

Leadership is seeing the possibilities in a situation while others are seeing limitations.

Leaders are always dissatisfied with current realities whenever or wherever they may apply, particularly when against the constitutional freedoms of our existence.

As your new chairman, I pledge to never engage in destructive actions with anyone within this body of leadership against another member of this commission.

I will avoid biased, selfish and narrow thinking that could be camouflaged by the term “Democrat” or “Republican.”

I serve at the pleasure of the majority commissioners, but I am committed to honor all of you equally and/or according to your needs and expectations of me — parallel, however, with the limitations and constraints of the chairmanship responsibilities.

I pledge to this body the assistance and resources to solve problems by relying on collective reasoning, rather than list them with the attitude of negativity. I will leave that to the media.

Woe to those who call evil good, for you have abused power and called it politics.

As your chairman, I declare this day to plant a new garden of leadership: peas, squash, lettuce, turnips.

First plant three rows of peas: patience, promptness, and prayer.

Next plant three rows of squash: squash gossip, squash indifference, squash unconstructive criticism.

Then plant five rows of lettuce: Let us obey God, let us be loyal, let us be true to our obligations, let us be unselfish.

Finish with four rows of turnip: turn up when necessary, turn up with a smile, turn up with a vision, turn up with determination.

Commissioners:

Watch your thoughts, they become your words.

Watch your words, they become your actions.

Watch your actions, they become your habits.

Watch your habits, they become your character.

Watch your character, it becomes your destiny.

Commissioners and community, I appreciate the opportunity to serve as your chairman.

It’s going to be an interesting year in the Vasco Smith County Administration Building.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker