James McMurtry is a songwriter’s songwriter, rightly celebrated for his evocative compositions over the course of more than three decades. Stephen King called him “the truest, fiercest songwriter of his generation,” and that highlights something unique about the Texas-based performer: writers of all stripes are among his biggest fans. And yet he doesn’t let such praise go to his head. Just listen to his song “Restless,” which begins with the lines:

She gets a little restless in the spring

She might follow the lines you sing

Bullshit though they are

‘Cos sometimes that’s just the thing

If delivered with panache and a certain grace

Perhaps when your father is novelist Larry McMurtry you have a certain perspective on any writerly talents you might possess, or accolades you might accumulate. Certainly that lends perspective on any similarities casual listeners might assume to exist between songwriting and prose-writing.

“I don’t take leads from any author,” he tells the Memphis Flyer. “I’m not a prose writer. My leads come from Kris Kristofferson, John Prine and people that write songs. It’s a whole different muscle. And you also have the melodic aspect, which we can’t really do without. People will compare my work to poetry but it’s not. I hear a couple of lines and a melody in my head and I chase it. If it’s cool enough to keep me up at night, I finish the song. With poetry, you don’t have to write for an instrument. Your voice is an instrument, so you write words that sing well. You don’t have to do that poetry — it doesn’t have to be sung, it doesn’t even have to be spoken.”

The key principle of songwriting, he says, it that “you don’t want to write words to tie your tongue. And I usually have to tweak it so I can sing it better. You want consonants that roll off the tongue, that drop in the pocket. That way you can talk it or sing it. If you study Kristofferson’s work, that’s kind of how he does it. He didn’t think of himself as a singer. You can sing the hell out of those words, or you can talk them. It gives you more options as to how to sell it. Roy Acuff talked about that. He said, ‘I’m not a singer. I’m a seller.'”

On Thursday, this consummate salesman and his band will be peddling their wares at Lafayette’s Music Room. And lest you think the lyrics, however singable, are the only thing going on with this artist, the music is just as carefully crafted. That makes for some very moving songcraft, as most critics have agreed. His albums Just Us Kids (2008) and Childish Things (2005) were hailed as milestones, with the former earning McMurtry his highest Billboard 200 chart position in two decades (since eclipsed by Complicated Game) and a few Americana Music Award nominations. Childish Things, a few years earlier, spent six full weeks topping the Americana Music Radio chart in 2005 and 2006, and won the Americana Music Association’s Album of the Year, with the politically charged “We Can’t Make It Here” named the organization’s Song of the Year. Still, he keeps evolving.

“I have explored more melodic approaches over time,” McMurtry notes. “The more I sing, the more my range increases. So two records ago I was writing some high stuff, high notes that I wouldn’t have tried earlier. And there’s one song on this record, ‘Blackberry Winter,’ that’s in a little bit higher range than I used to do. But I don’t know that it really matters. It makes it harder!”

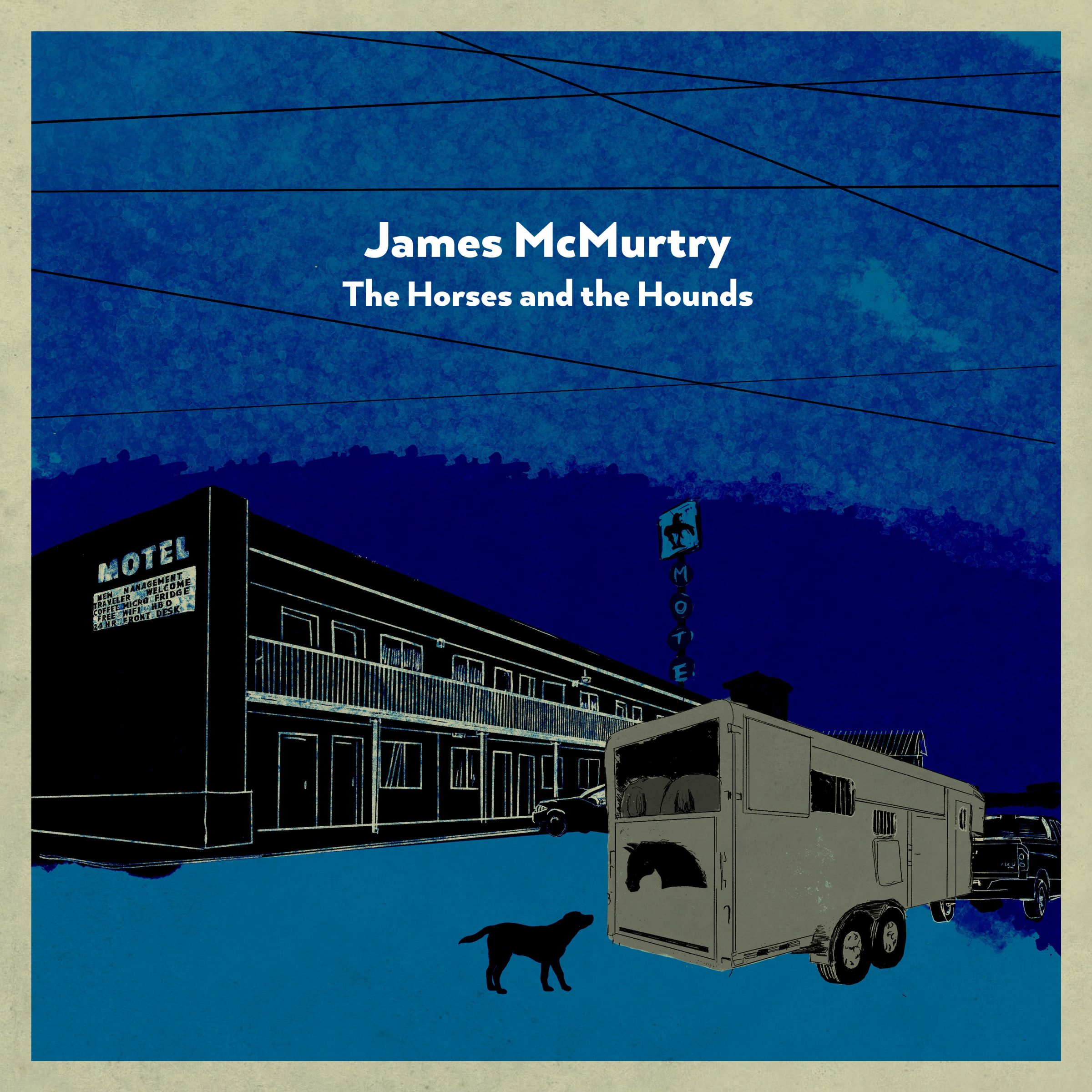

That record, The Horses and the Hounds, released by New West Records in 2021, is classic McMurtry, spinning empathetic, wry tales full of the despondent feel of small town America on the skids. “That’s been a thread through most of my work for most of my so called career,” he admits. “I get my details through the windshield because we spent a lot of time going down the highway. But I know that feeling of wanting to get out of a small town. That’s kind of the culture I came from. My dad escaped from a small town in Texas and went to school, and most of his friends were first-generation-off-the-farm grad students. So that was kind of how I was raised. It instilled a skepticism of rural, small towns in me which I later saw firsthand from living in Lockhart, Texas. And I even wound up back in my dad’s hometown for some of the time. It was just like he said!”

James McMurtry and band play Lafayette’s Music Room on Thursday, September 28th at 7 p.m. $25 advance/$30 day of show. Click here for tickets.