Kroger

Kroger

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Food waste is in the crosshairs of city officials and local environmental leaders with a plan to reduce it by 50 percent by 2030.

The Memphis Food Waste Project is led by the nonprofit Clean Memphis and joined by a coalition of private and public partners, including the City of Memphis, the Memphis and Shelby County Office of Sustainability and Resilience, Memphis Transformed, Project Green Fork, the Natural Resources Defense Council, Compost Fairy, Epicenter, Kroger, the Mid-South Food Bank, and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. Together, the groups will push to reduce food waste to save money, improve the environment, and help ensure fewer Memphians go hungry.

Clean Memphis executive director Janet Boscarino said food waste and packaging now comprise 30 percent of landfill volume. It also produces the most methane gas (the most harmful gas), she said. These reductions will aid city leaders to meet goals detailed in the Memphis Area Climate Action Plan.

“The City of Memphis can service as a leader in developing a more sustainable food systems approach, reducing wasted food, and the resulting wasted labor, land, and money, as well as increased pollutants by supporting waste diversion and generating useful products such as finished compost with this diverted food waste,” reads a December proclamation from Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Dirty work: the BFI landfill near Millington

Food waste can be diverted from restaurants, hospitality providers, and other food producers in the city, according to the proclamation. Food from those sources has “great rescue potential” for food “that would otherwise go to waste.” The food could be retrieved and donated to those in need, Strickland said in the proclamation.

Boscarino said the United States spends $218 billion (or about 1.3 percent of the gross domestic product) growing, transporting, and disposing of food that is never eaten. She said the waste numbers are staggering given that one in eight Americans are food insecure — lack reliable access to food because of money and other concerns — and that one in five Memphians are food insecure.

Waste occurs along nearly every stop in the food supply chain here, Boscarino said. Some food spoils as farmers can’t move it to market quickly enough. Some food is tossed as it may not meet cosmetic standards, even though it has the same taste or nutritional value. Food continues to spoil as it moves through the supply chain to grocery stores, restaurants, and hospitality venues, she said. But the largest food-waste sector “by far,” she said, is in homes.

“We over-purchase, we don’t store things rights, we don’t eat leftovers, we don’t use all parts of the food, and we’re not composting at a level we need to,” Boscarino said.

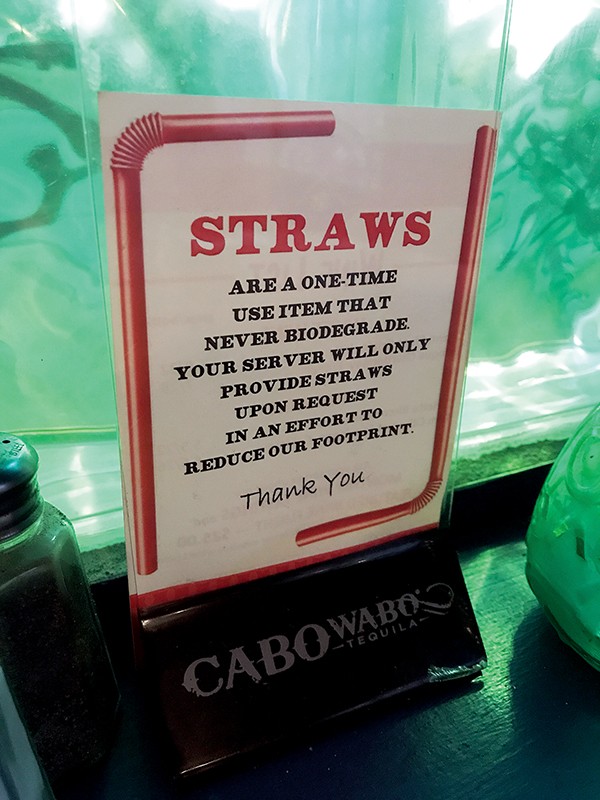

To combat all of this, Project Green Fork will be working with restaurants, hospitality venues like hotels, and event spaces like FedExForum to donate their food and avoid waste. Memphis Food Waste Project members will educate residents on how to more sustainably shop for groceries, how to store food, how to freeze food, and how to “fall in love with leftovers,” Boscarino said.

Test your food waste knowledge with an online quiz at www.cleanmemphis.org.

Read Strickland’s proclamation here:

[pdf-1]

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips