Though you may have read about Steve Lee in the Memphis Flyer before, none of those articles have really been about him. That’s the paradox of being an educator who devotes so much time to public service, as Lee has done since founding the Memphis Jazz Workshop (MJW), one of the city’s premier institutions in music education, in 2017. The scope and impact of that nonprofit have been so great that it’s easy to forget about Stephen M. Lee, the virtuoso jazz pianist and recording artist. He’s getting in two lifetimes’ worth of existence for the price of one.

A clue to the mystery of how Lee manages to accomplish so much in both worlds can be found in the title of his new album, In the Moment. That’s clearly where he lives, as one listen to his deft improvisations will tell you. Composing in the moment, on the spot, is at the heart of jazz, and jazz is at the heart of Steve Lee. But beyond the album itself, one senses that it’s been his ability to improvise as the director of MJW that’s led to its impressive staying power. “We’ve been at about seven locations in the last seven years,” he says. Yet the MJW not only survived the onset of Covid; it has thrived ever since. “We’ve averaged from 50 to 70 students for each session since 2020,” he adds, and those numbers are only half the story.

While those individual and group lessons, taught to teens during spring, summer, and fall sessions every year, are at the core of what Lee’s nonprofit has accomplished, perhaps the greater indicator of MJW’s success has been the degree to which its students have been performing for live audiences. Case in point, this Friday, July 13th, the MJW students will command the stage at the The Grove at the Germantown Performing Arts Center (GPAC), featuring “the area’s most talented young jazz musicians in a variety of combos, ensembles, and even a big band,” as the GPAC site notes.

“This will be our third year [at The Grove],” Lee says. “It’s a great location, and they pretty much donate the space to us. Paul [Chandler] and his staff are great — the only thing we have to do is show up. It’s a great opportunity for the organization.” Moreover, MJW players can be seen on the third Saturday of every month as the featured attraction at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art (the next event being August 3rd, noon to 2 p.m.).

And this is where the two lives of Steve Lee begin to meet, as some MJW students distinguish themselves enough to finally play on the bill with the maestro himself. That too will be apparent this Sunday, the day after the GPAC show, when Steve Lee will headline at the Sunset Jazz Series at Court Square.

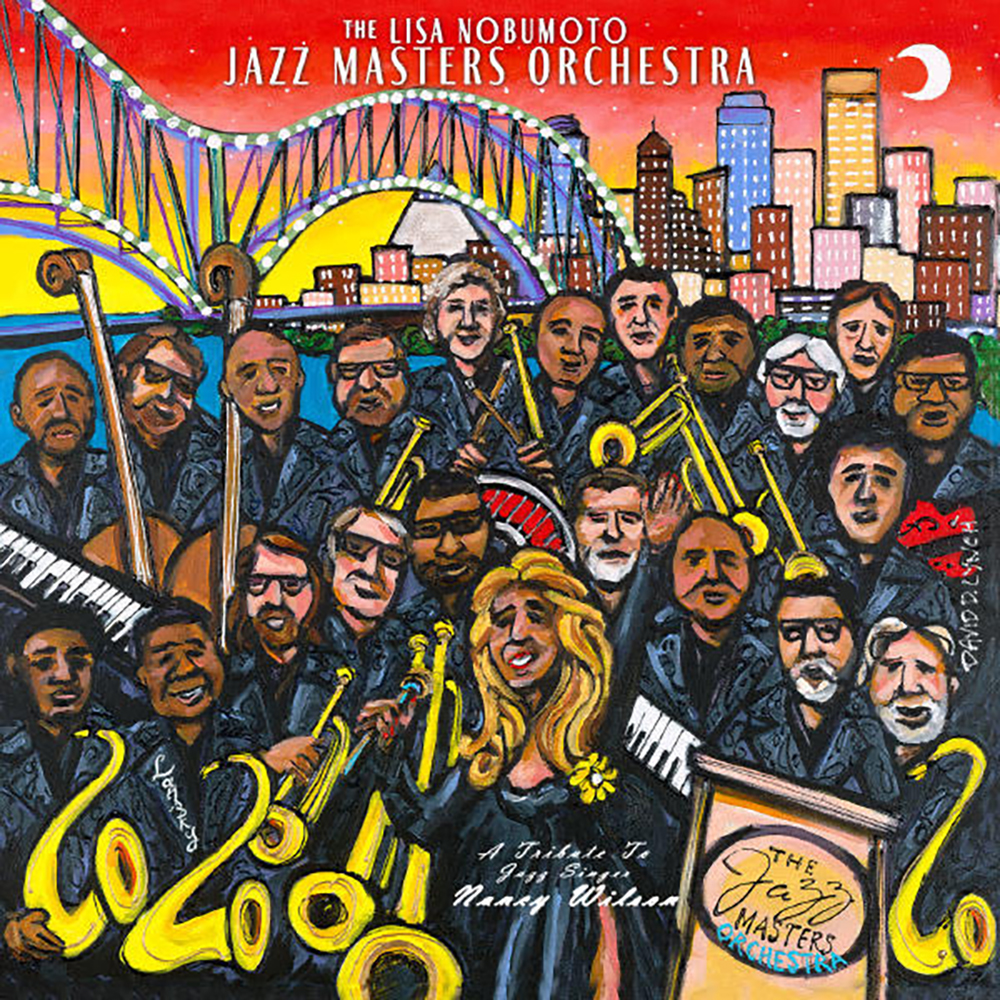

“A few students will be playing on July 14th with me,” he says with a hint of pride. “The drummer, Kurtis Gray, is just 18. He just graduated from high school.” Flyer readers will know his name from our story on the Jazz Ensemble of Memphis, produced by David Less in emulation of the classic 1959 album, Young Men from Memphis: Down Home Reunion. “And the bass player’s also one of my former students, the drummer’s brother, Kem Gray Jr.,” Lee adds. “And then the sax player, Michael Price, just graduated from UT-Knoxville. He’s about to go to [grad school] at Rutgers.”

When Price was just a junior at UT, he shared some thoughts with the MJW Instagram page that may stand as the greatest endorsement of the program to date, saying, “The life skills that I gained from the Memphis Jazz Workshop were discipline, communication, honesty, support, love, mentorship, and community. … Understanding the intricacy of these different skills and their relationship to music is vital and you need to have all of these qualities in order to seriously pursue music, and I’d go as far as to say to succeed in life.”

In a way, it harks back to the glory days of Manassas High School, which trained generations of jazz greats here, starting in 1927 with educator Jimmie Lunceford, who polished his school band into a nationally recognized recording group, the Chickasaw Syncopators. “I think [MJW] is a continuation of what he was doing,” Lee told me in 2018, speaking of Lunceford. “But Memphis never had a jazz workshop like the workshops we have now. They always had jazz in the schools.” Today, Lee is forging that culture of excellence on his own, outside of any infrastructure, finding venues to hold classes anywhere he can, albeit now much more recognized by funding institutions, and always recruiting his faculty from among the city’s best jazz players.

He benefited from local greatness himself, when he studied under the great Memphis pianist Donald Brown (on the faculty at UT-Knoxville for many years), which in turn led to Lee’s years in New York City, prior to his return to Memphis. All that may explain the dedication and determination with which he’s thrown himself into leading the MJW. And the organization’s success has reflected well on both Lee and the city, a fact that was commemorated this past April when Lee received the Memphis Symphony Orchestra’s (MSO) Eddy Award, recognizing him as community leader in music.

“As chair of the Eddy Award selection committee, we agreed that Steve Lee embodies the award’s meaning as his incredible career has brought young people from all backgrounds, races, and life experiences together through the power of jazz music,” said Jocie Wurzburg in a statement on behalf of the MSO. Now, this weekend will show off both the MJW and Lee in their best light.

And, as he explains, his two skills feed each other, though balancing them has been demanding. “I have to be the teacher, the principal, the janitor, all of it,” he laughs. “I’m not one of those executive directors who just lets other people do it. Because, you know, it helps me. I don’t really have a lot of time to practice. So showing information to these students, that’s a part of practicing because I still have to sit at the piano and show them what I want them play. So it helps. That’s why I enjoy doing it. Because it is a form of practice, and you know, the students motivate me.”