For Lisa Nobumoto, jazz is more than just a genre. It’s a mission, a way of life. That much is obvious with last week’s release of A Tribute to Jazz Singer Nancy Wilson by Nobumoto and the Jazz Masters Orchestra, arguably one of the most ambitious jazz projects to come out of Memphis in decades, and a labor of love for the singer that’s been years in the making.

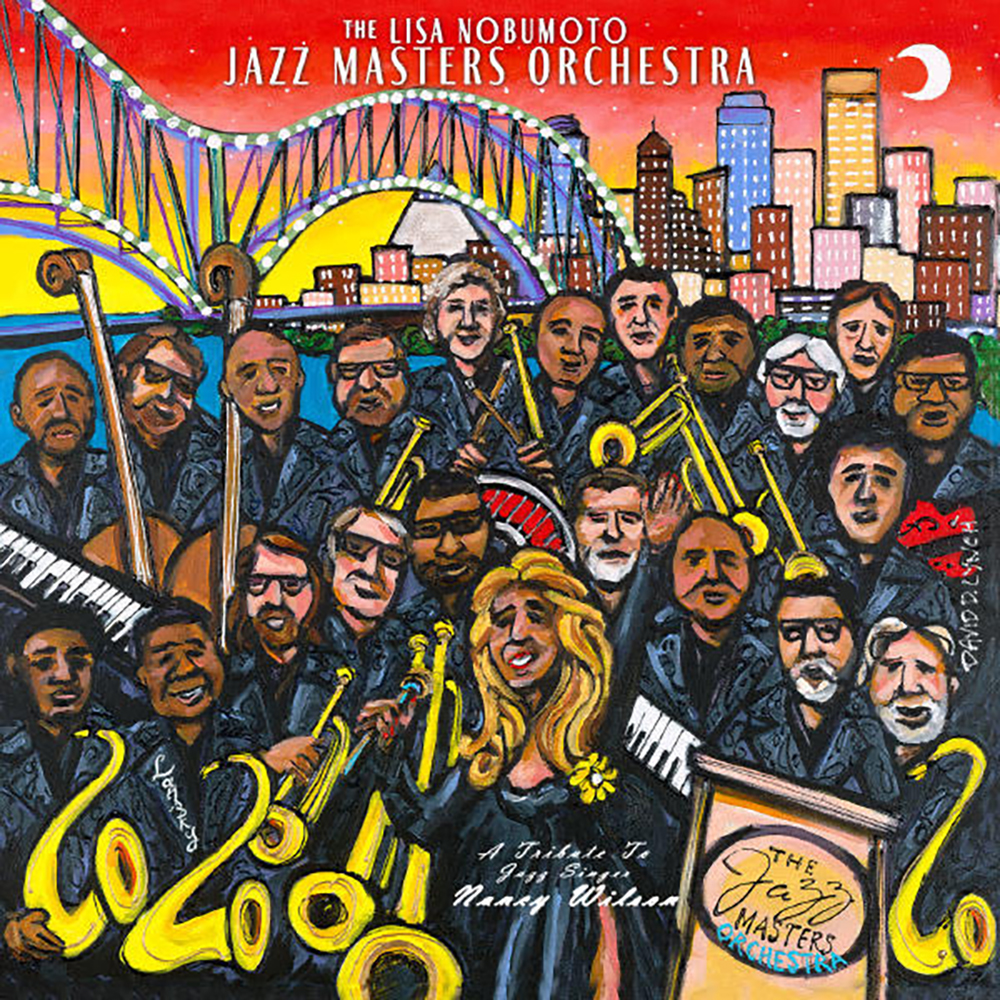

That’s partly due to the scale of the ensemble, a 20-piece orchestra that’s a veritable who’s who of jazz heavyweights working in Memphis today. The album’s arrangements were done by Rhodes College faculty member Carl Wolfe, co-founder of the Memphis Jazz Orchestra, and the group was conducted by Jack Cooper, director of jazz studies at the University of Memphis. Pianist Eric Reed, the sole non-Memphian, is a lecturer and artist-in-residence at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the remaining players are similarly well-schooled professionals. And the proof is in the listening, as the group brings Wolfe’s arrangements to life with fluidity and nuance. Sailing over that swinging foundation, of course, is Nobumoto’s voice.

A native of California with family roots in the Mid-South, Nobumoto relocated to Memphis some five years ago and promptly founded the Jazz Masters Series nonprofit to pursue her vision of fine jazz. That vision was honed over decades of performance on the west coast and touring the world. Her late husband, George Gaffney, was Sarah Vaughan’s pianist, but Nobumoto worked with many greats in Los Angeles. “I worked with Teddy Edwards for 32 years,” she says, “and the other players in that band were Jimmy Cleveland, Gerald Wiggins, Al ‘Tootie’ Heath, Nolan Smith Jr., and Larry Gales.” In short, she’s worked with some of America’s greatest musicians.

During her L.A. days, none other than legendary jazz scribe and composer Leonard Feather wrote, “Lisa Nobumoto’s distinctive phrasing and timbre could earn her a significant role on the upcoming vocal scene,” and indeed, Music Connection magazine named her the top unsigned artist in Los Angeles at the time.

Bringing that experience to Memphis, Nobumoto knew early on that she wanted to pay tribute to Nancy Wilson, a master of not only straight-ahead jazz but blues, soul, pop, and R&B as well. Beginning in the early ’60s, “The Girl with the Honey-Coated Voice,” as she was known, was a pop star of sorts, back when such a thing was imaginable for a jazz artist. “My mom played Nancy Wilson over and over and over again when I was a child,” says Nobumoto. “I knew every song.” Later, as she delved into Wilson’s work more deeply, Nobumoto found who Wilson had found her inspiration from: Little Jimmy Scott.

To those familiar with Scott’s soaringly high, somewhat androgynous delivery, that makes perfect sense. “He’s my favorite male singer vocalist of all time,” notes Nobumoto. “I met him and heard him perform on several occasions, and he’s the only man I’ve ever seen start a show with a ballad — and then go on to a slower ballad. He could have you crying, where you can’t hold your tears back. And Nancy basically took his sound. I mean, she studied him a lot. They came from the same part of Ohio.”

Nobumoto has a gift for interpretation, negotiating this material with a grace akin to Dinah Washington and echoing Wilson’s conversational style — but always with Nobumoto’s individual stamp. “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” is transformed into a steamy, confessional ballad, worlds away from Frankie Valli’s pop stomper. Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” is more up-tempo than either the original or Wilson’s 1966 version, taking it into boogaloo territory, yet with a relaxed delivery that brings wit and humor to the song. With Wolfe’s arrangements, the album’s timeless jazz classicism makes it hard to pin down chronologically: It could have been made any time in the last half century.

Recalling the two legendary singers who most inspired her is bittersweet for Nobumoto, who performed with so many jazz greats before moving to Memphis. “They’re just gone. Everybody I knew from that era, so to speak, has passed. But when you get to a certain age, you stop thinking about money or fame and you’ll give up everything just to live this broke-ass lifestyle. And I get to see things like this manifest. I really want the nonprofit to build into something that I can leave behind for someone else to carry on.”