Jean Rhys is one of my favorite writers. Her early autobiographical novels are singular depictions of marginalized lives, the lives of women in a man’s world. In some of her novels, men represent a structure and a security her heroines don’t quite believe is possible. Rhys was born Ella Gwendolyn Rees Williams on the Caribbean island of Dominica, but she moved to England to attend school. For a while she led a wayward life of alcohol and opportunistic, inappropriate suitors. She met Ford Madox Ford and, under his influence, wrote those early novels which paralleled her life in disturbing ways. Yet, for all their pain and sadness, they shine with a light that is honest, compelling, and eccentrically rendered. In the 1940s, she disappeared from public life and quit writing. Then, in 1966, in a miraculous end to her unconventional writing career, she published her greatest novel, a brilliantly realized prequel to Jane Eyre, The Wide Sargasso Sea.

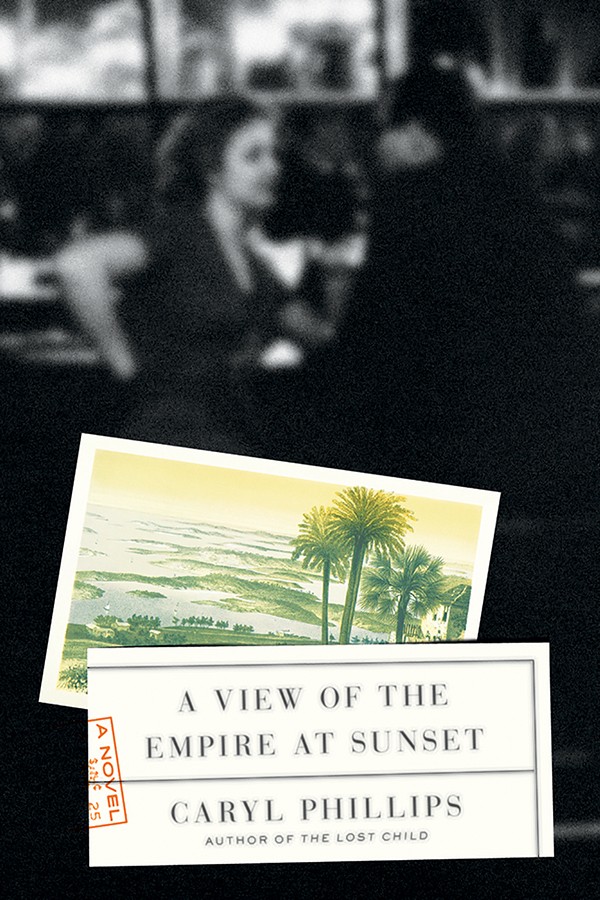

In A View of the Empire at Sunset, Caribbean novelist Caryl Phillips gives us a fictionalized account of Rhys’ life that works as both biography and fiction. He manages to limn Rhys’ style while not falling fully under its sway and abandoning his considerable novelistic abilities. You can taste Rhys, but it’s still Phillips’ exotic stew. Here she is called Gwennie. I was absorbed initially in waiting for young Gwennie to become one of the 20th century’s best novelists. But Phillips is after more than this. His narrative is about homeland, family, alienation, loneliness, and need. His Gwennie is a masterfully drawn character, as dissolute, yet as determined, as Rhys’ tragic characters. Is Rhys’ story her characters’ story? Yes and no. While there is much to suggest that Rhys drew from her own life, it is a disservice to her remarkable novels to see them only as thinly disguised autobiography.

Phillips traces Gwennie from her birth in Dominica to her schooling in London. When she abandons school to tread the boards, she encounters and learns from other wannabe actresses. She abandons this as well; she wanders; she fails continuously at attempts to find herself. Comparing herself to a friend she says, “Unlike herself, Ethel was busy; unlike herself, Ethel had not stooped to love and thereafter found herself sitting idly about waiting for a man to whisper kind words in her ears as he unfolded his wallet.”

She is married twice, loses a child, and has a daughter who survives her. She drinks. Her marriages are unhappy. “Is it possible, she wonders, that she might well be participating in a modern marriage: attachment and detachment at one and the same time?” Poor Gwennie!

Phillips is a colorful writer, even with such dour material. His sentences are as sharp as etchings in glass. And he’s a storyteller of the first water. His Gwennie is a sad wreck; often one wonders where the triumphant Jean Rhys is in this gloomy, inchoate life. Of his heroine Phillips says, “She understands that it doesn’t matter where you are, on land or sea, you always hear the noises before you see the light — and then soon after, the new day will arrive to torment you.” But, perhaps the most telling statement about Gwennie is this: “Mabel always insisted that the key to happiness was to simply stay quiet and make them fall for you. Eventually she learned how to do this, but it was afterward that always proved difficult, when she invariably decided that she no longer wished to remain quiet.” Of course, we know the conclusion. She does not remain quiet. She emerges as one of the most unforgettable female voices in all of literature.

In the end, A View of the Empire at Sunset is more novelistic than biographical. If Phillips doesn’t give us the Jean Rhys, he gives us a Jean Rhys, a fascinating portrait of a clever, sensitive woman, who never quite gets where she’s going. At novel’s end, Wide Sargasso Sea cannot even be discerned on the distant horizon, but Caryl Phillips’ Gwennie is still moving, still moving on.