In the spring and summer of 1862, a Union general named Samuel Curtis led the Army of the Southwest from southern Missouri toward Helena, Arkansas. It was a four-mile procession of soldiers, horses, wagons, and artillery, but during the months-long march, the numbers grew: As the army passed through, slaves left their homes to join the line, pursuing freedom under the protection of Curtis’ forces.

Some Union commanders refused to allow fleeing slaves behind their lines. But Curtis, an abolitionist, took them in as contraband, even issuing papers declaring their freedom.

By the time Curtis reached Helena, on July 12th, some 2,000 “freedom seekers” had joined his line. With word spreading that refugee slaves were not turned back, others began to flock to Helena as well, overflowing makeshift contraband camps around the city. Soon, a hospital and school for freedmen were established.

Following the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, the Year of Jubilee was celebrated and forces were raised for a U.S. Colored Troops regiment out of Helena. By the end of the war, more than 5,500 former Arkansas slaves would fight for the Union, with more than 85 percent coming from the Delta.

Forgotten History

You can be forgiven for not knowing this story. I grew up in eastern Arkansas, not far from Helena, and was never taught it. Until recently, few in Helena knew about this chapter in their town’s history.

The story of Helena’s freedom seekers is not unique among Southern stories soon buried under Lost Cause mythology and officially forgotten. Three years after Curtis marched into Helena, former slaves in Charleston, South Carolina, dug up Union soldiers who had perished in a Confederate prison and were buried in a mass grave. The former slaves gave those who helped free them a proper burial and then commemorated them with a massive parade, speeches, and songs. It was the birth of what we now call Memorial Day.

“People who like to talk about ‘revisionist history’ always hit on that they’re changing this story that’s been told for years and years and years,” says Joseph Brent, a Birmingham-bred, Kentucky-based historian whose company Mudpuppy & Waterdog consults on public history projects. “That story was modeled by the United Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy, and it’s one of those weird situations where the losers wrote the history. That’s the hardest thing to break through. When your dad and your granddad and your great-granddad tell you these stories, it’s kind of hard to say, well, they weren’t right.”

The Lost Cause itself was a revisionist spin that has held sway in the South, to one degree or another, for generations, promulgated not just by the vanquished and their descendents, but by blinkered academics and the popular culture, driven by the post-Reconstruction willingness to sacrifice black freedom for the cause of white reconciliation.

But that’s changing. In places like Charleston and Helena, the hard work of severing a Southern view of history from a Confederate one is finally being done.

The first “decoration day” was a memory repressed by post-Reconstruction Charleston and lost until Yale historian David Blight rediscovered it several years ago.

But Charleston recognized this part of its history in 2010, with a marker at the original site. And now Helena is in the midst of an ambitious “Civil War Helena” campaign to rediscover, interpret, and present the full measure of its own community history. On February 23rd, as Memphis wrangled anew over the future of its “Confederate” parks and monuments, Helena dedicated Freedom Park on the site of one of its former contraband camps, giving those freedom seekers some long-overdue recognition.

The Helena Story

“When you talk about the Civil War in the South, you think mainly of Confederates. And that’s what had been promoted here in Phillips County,” says Cathy Cunningham, a community development consultant for Southern Bancorp and one of the civic leaders spearheading the Civil War Helena initiative in the economically depressed Delta town, 70 miles south of Memphis.

“We did have seven Confederate generals [who came from the county], which is great. But there’s so much more to the story than that,” Cunningham says.

For generations, those seven generals and the July 1863 “Battle of Helena” — in which Union forces held the city from a Confederate counterattack — were the extent of the history Helena acknowledged.

“If you asked anyone, it was those two things,” says Katie Harrington, director of the Helena-based Delta Cultural Center, which is an offshoot of the Arkansas Department of Heritage.

Rescuing the city’s broader Civil War-era history began in the early 1990s, with the work of Ronnie Nichols, a Little Rock native and African-American Civil War buff who was then the Delta Cultural Center director. Nichols first proposed building a replica of Fort Curtis, the Union stronghold that was forged, in large part, by freed slaves. And he organized the first Battle of Helena reenactment in the city.

“At some point, people became locked in time, and really one of the greatest assets [in Helena] is the Civil War history,” says Nichols, who served as a technical adviser on the film Glory, about black Union troops, and is now a historical consultant based out of Potomac, Maryland. “It’s something that people had not developed and seemed to almost work around as opposed to using it as a draw. But Helena was really the crucible of the Civil War in Arkansas, so it had a very important role.”

“Because of Ronnie’s research, we thought it was something very exciting. It’s just taken awhile to pull it together,” Cunningham says. “When he was interested in doing this, we, as a community, may not have been ready for it. I think now we are.”

The change began with the Delta Bridge Project, a public-private community development initiative spurred by Southern Bancorp in 2003.

“The community came together and decided what goals they wanted to pursue,” Cunningham says. “Within tourism, the people at the meetings — and we had more than 600 community members attend — put an emphasis on Civil War Helena.”

The project has been led, jointly, by Southern Bancorp, the Delta Cultural Center, and the recently formed Helena Advertising and Promotion Commission. They called for proposals in 2008 and hired Mudpuppy & Waterdog — Joseph Brent and his anthropologist/archaeologist wife, Maria Campbell Brent — to help develop an interpretive plan.

“We chose Mudpuppy & Waterdog mainly because they weren’t just talking about troop movements and the battle. They were interested in the effects [the war] had on the people who came here,” Cunningham says. “What did the Confederate women feel like once they were left here? We liked that aspect of it. They gave us much more than we expected.”

“In our proposal, we said we wanted to tell everybody’s stories. There was so much going on in Helena that had not been told before,” Maria Brent says.

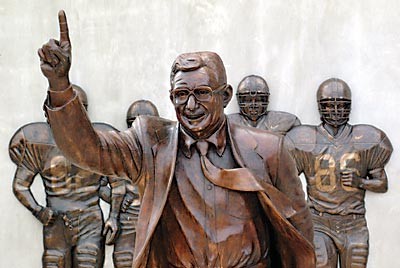

The result has been a 25-site plan that tells a comprehensive history of Helena during the war. Before Freedom Park, there was New Fort Curtis, a realization of Nichols’ initial vision, which was built to three-quarter scale three blocks south of the original site (which is now a church) and which was dedicated in 2012. A new statue of Helena’s most famous Confederate general, Patrick Cleburne, adorns the path to downtown’s Helena Museum. Cleburne is buried in Helena’s Confederate Cemetery, which sits atop a hill in Maple Hill Cemetery, overlooking the adjacent Magnolia Cemetery, an African-American resting place containing the graves of Civil War veterans and Reconstruction-era leaders.

From the soon-to-be refurbished Battery C, you can survey the entire city and see how the Battle of Helena played out. For military buffs, it’s fascinating. But the Civil War Helena project also tells other stories, from those of the freedom seekers to those of left-behind Confederate women living under Union control. This comprehensive approach to history remembers the loss of the war while also celebrating the liberation. If not unique, this approach is still rare in the South. But it’s becoming less so.

“The Park Service, a few years ago, had a ‘come to Jesus’ moment,” Joseph Brent says. “They decided that in all of their Civil War parks they were going to talk about slavery and talk about how slavery was the cause of the Civil War.”

Brent mentions a project in Corinth, Mississippi, which Mudpuppy & Waterdog worked on, that details its contraband slave camp. “That’s about the only other place I know where this is being told,” he says. “But I think, as a whole, this is a direction in which a lot of people want to go.”

Everyone involved in the Civil War Helena project insists that resistance to this comprehensive approach, while not nonexistent, has been minor.

“Everything is fact-based. Everyone has their own opinion. Some may not want to wear a Union uniform, but that doesn’t change the fact that we had a Union fort,” Harrington says. “We’re not Disney World.”

“Some people, if you show them the history and that it’s traced through primary documents, are willing to listen. But some people just aren’t,” Joseph Brent says of the general challenge of telling a comprehensive Civil War history in the South. “But if you base interpretation on good, solid research, you can tell a story that gives everyone a voice. Civilians and African Americans and Confederates and the Union.”

History Belongs to Us

It helped, in Helena, that the project has been couched as an engine for much-needed economic development.

“We do a lot of battlefield preservation and interpretation,” Maria Brent says. “You deal with people who seem to have leanings in [the Confederate] direction. But with most of the sites that we work with, one of their motives is developing tourism. They know that the more inclusive they can be, the broader the appeal can be to nontraditional visitors. And they need that.”

“Because of the physicality of the place, it really lends itself to that,” Nichols says of the prospects for Civil War tourism in Helena. “We would have people who would come in from Minnesota and Missouri and so forth and say, ‘My great-great-granduncle served here, and can you tell me or show me something about it?’ So it wasn’t just about black history. People were coming in who knew about the place, but there wasn’t anything to show. So the whole idea was that we needed to start developing what people are asking for.”

Helena is well-positioned between Shiloh in West Tennessee and Vicksburg in Mississippi, both of which draw hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. The hope is that Civil War Helena can tap into a decent percentage of those tourists.

“We think Helena is well located to draw visitors from each of those places,” Maria Brent says. “Until recently, there hasn’t been anything to really explain what was going on in Helena. So it’s been under-visited. It’s mostly been known for Patrick Cleburne, and that’s where most of the visitation has come from, pilgrimages to the gravesite.”

“Helena needs anything it can get,” Harrington says. “I want to be high with my expectations, but anything is better than nothing. Helena’s had a lot of ups and downs.”

In addition to tapping into the existing heritage tourism market, the hope is that a more comprehensive approach to the history can also help broaden that tourist base. This means reaching beyond the stereotypical (or maybe it’s just typical) Civil War tourist — the older white man interested in battle logistics — and reaching more African Americans, more women, and more families.

“I think everyone agrees that if you can find someone you can relate to, it’s easier to be interested,” Harrington says of the approach. “You don’t have to be a Civil War historian to catch onto the story.”

This broad approach may be good for business. But it’s also good history. The brochure touting Civil War Helena reads: “This is the story of our nation’s struggle. This is our history.” “Our” means all of us.

And that hints at what’s most refreshing about it: This is Southern Civil War history seen through a contemporary American lens rather than a Confederate lens.

Nichols mentions that, while at the Delta Cultural Center, he was the only African-American member of the Arkansas Civil War Roundtable. That Nichols is an anomaly as a black Civil War buff is itself an indictment of the way this history has been presented.

The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote eloquently on this subject for The Atlantic last year, chronicling his own lonely experience as a young, African-American Civil War buff in an essay bluntly titled “Why Do So Few Blacks Study the Civil War?”

“[O]ur general sense of the war was that a horrible tragedy somehow had the magical effect of getting us free,” Coates wrote. “Its legacy belonged not to us, but to those who reveled in the costume and technology of a time when we were property.”

Then he continued:

“Our alienation was neither achieved in independence, nor stumbled upon by accident, but produced by American design. The belief that the Civil War wasn’t for us was the result of the country’s long search for a narrative that could reconcile white people with each other, one that avoided what professional historians now know to be true: that one group of Americans attempted to raise a country wholly premised on property in Negroes, and that another group of Americans, including many Negroes, stopped them. In the popular mind, that demonstrable truth has been evaded in favor of a more comforting story of tragedy, failed compromise, and individual gallantry. For that more ennobling narrative, as for so much of American history, the fact of black people is a problem.”

“African Americans are Southerners too, and their history is as significant as that of white Southerners,” Joseph Brent says. “That’s always the story that’s been left out. And it’s great when communities can embrace and tell these stories and involve African Americans in their Civil War history — because it is their history as much as it is the Southern, white, Confederate story. Let’s face it, many, when they had the opportunity, did join the Union Army, and they did fight. It’s a complicated history. As more of these stories come out, it adds to the fabric of our history.”

Letter to Memphis

The comprehensiveness of the historical interpretation in Helena stands in stark contrast to Memphis’ embattled parks.

The former Confederate Park, on Front Street, is historically incoherent by comparison. It’s meant to commemorate the Naval Battle of Memphis, on June 6, 1862, which was a Mississippi River precursor to the following battles in Helena and Vicksburg.

The land atop the bluff where the park is located was where civilians gathered to watch the gunboat battle on the river below. But the Union won this battle in short order, and Memphis, like Helena, was Union-occupied for the remainder of the war.

The name “Confederate Park” didn’t convey this history. It conveyed the attitudes of those who dedicated the park in 1908, after Reconstruction was abandoned and former Confederates had reclaimed the South. Similarly, the statue of Jefferson Davis at the center of the park has little to do with the actual history that took place there, beyond Davis’ role as president of the Confederacy at the time. Davis did spend a few years living in Memphis but much later. The inscription on the Davis monument refers to “The War Between the States” and asserts, without a trace of irony, that Davis, the ultimate secessionist leader, was “a true American patriot.”

Other elements that dot the park include a couple of markers about Confederate-connected Memphians, a World War I medical monument, and, most incongruently, a 1952 Jaycees monument displaying the Ten Commandments.

If the message of the former Confederate Park is muddled, the former Forrest Park comes across as a civic abdication to the Lost Cause. While Forrest’s relevance to the history of Memphis is incontestable, his meaning is, of course, fiercely contested. And nowhere is this acknowledged. There is no reference to his history as a slave trader or his post-war role in the foundation of the Ku Klux Klan. An inscription says that the statue was erected “in honor of [Forrest’s] military genius,” without, of course, an acknowledgment that these military exploits were performed in the service of an attempt to preserve and expand slavery — as if “military genius,” in itself, is worthy of being honored. Instead, there’s another inscription, from “poet laureate of the Confederacy” Virginia Frazer Boyle, that uses the words “God,” “titan,” and “glory” in four lines.

Cultural products tend to reveal the circumstances of their production. Gone With the Wind is “about” the South during the Civil War era. But, released in 1939, the real meaning of the film and its popularity come from what it says about how people in 1939 viewed this history; how seductive the lies of the Lost Cause were for most of the country at that time.

The Jefferson Davis statue on Front Street was erected in 1964, when much of the white South was pushing back against the demands of the civil rights movement and acting in defiance of federal attempts to impose integration and other measures of justice. In that context, is the Davis statue a Civil War monument or a segregationist monument?

The remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest and his wife, Mary, were moved from their initial resting place at Elmwood Cemetery to Forrest Park in 1905 by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Is the Forrest statue a Civil War monument or a Jim Crow monument?

These “Confederate” parks and monuments have always been bad or, at best, incomplete history. But there was a time when they reflected the values of the communities that built them. That time has passed.

And so, with the fates of these parks in limbo, this perhaps unwanted moment presents an opportunity — not to erase history but to rescue it. In Helena, they’ve managed an honest, full reckoning with history that also honors contemporary community values. Memphis lacks the same kind of opportunity and need to leverage Civil War history for economic development. But as far as presenting true public history and finally resolving a long-festering civic embarrassment, the city could do worse than to look south for inspiration.