As University of Memphis Film Professor Marina Levina likes to say, all horror is rooted in body horror. From the bloody dismemberment of slasher films to vile mutations of David Cronenberg, the entire genre rests on a bedrock of biological revulsion. The principle extends all the way back to the work where sci fi and horror first converged. The star of Frankenstein was a monster stitched together out of discarded body parts. Feminist critics have pointed out that, at the time Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, she had recently had a miscarriage. The darkest fears of humanity are rooted in the squirmy realities of our reproduction.

Annihilation, the new film from Ex Machina director Alex Garland, begins with a bit of biology. Lena (Natalie Portman) is lecturing her class at Johns Hopkins University over video of dividing cells. All life, she says, has its origins in this simple event, before revealing that the cells on the screen are cancer.

Lena met her husband Kane (Oscar Isaac) while they were both in the Army. She got out, but he stayed and became an elite special forces fighter. A year ago, he left for a secret mission and was never seen again. Lena never got any word from the government on what happened to him, and had given him up for dead — until he suddenly shows up at their house with very little memory of what has transpired. But Lena’s emphatic questioning is interrupted when Kane has a seizure. On the way to the hospital, the ambulance is intercepted by government vehicles, and soon Lena wakes up in a mysterious hospital room with no recollection of how she got there.

This won’t be the first time Lena wakes up disoriented in this creepy, slow burn thriller. Dr. Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh), a government psychologist, reveals to her that Kane’s mission was to Area X, a spot on the swampy Gulf Coast that is surrounded by a mysterious shimmer, some kind of visible force field that appears like a giant soap bubble. The shimmer first appeared three years ago, and it has been steadily growing in size. No one who has gone in has ever come out — except Kane, and the authorities are unsure how he got from the Gulf Coast to Baltimore without anyone noticing. As Kane clings to life, Lena is recruited on a desperate mission to get to the lighthouse at the center of Area X. What the team of four women finds will be crucial to preserving the future of life on earth.

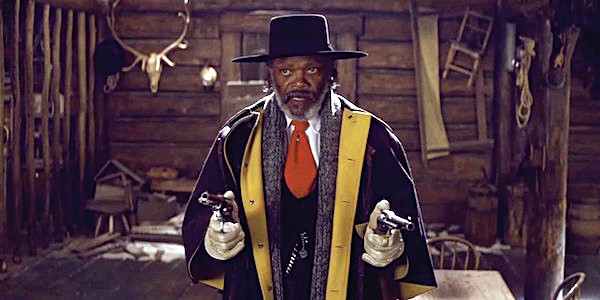

Natalie Portman stars in Annihilation, Alex Garland’s new sci-fi/horror film.

Annihilation is adapted from the novel of the same name by Jeff VanderMeer, but its concept has deep roots in H.P. Lovecraft’s 1927 “The Colour Out of Space,” where a meteorite brings a strange chromatic plague to the swamps of New England, and Roadside Picnic, a 1971 Russian science-fiction novel where teams of dragooned men must brave a zone where the laws of physics break down in order to recover alien artifacts. Garland’s pacing and staging take inspiration from Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky’s adaption of Roadside Picnic. Inside Area X, Lena and her crew find both wonders and horror, with rainbow-colored plants and half-human monsters.

Portman is the focus of the picture, and she carries the weight of the production with the same kind of calm professionalism her “warrior scientist” exudes when being presented with mind-bending sights and concepts. Jason Leigh, the secretive leader of the expedition, is uncharacteristically wooden in the first half, but loosens up as the going gets weirder and more paranoid. Isaac’s role is barely there in this female-driven story, but in a series of cleverly constructed flashbacks, his charisma provides relief from the horror slog through the psychedelic swamps.

But the acting, while serviceable, is not really the point. Lena and Kane’s relationship drama feels like a distraction from Garland’s mixture of horror beats and big think concepts. Even as it relies on horror tropes for shape (why do a group of trained scientists and soldiers insist on splitting up like they’re in the Blair Witch Project?) Annihilation‘s mission is to plumb the depths of Lovecraftian existential fear. The universe is a big and scary place that cares nothing about the problems of two little people, or even one little planet.