The story goes that there was a time William Eggleston didn’t give much of a thought to photography. And then, in the late 1950s, a friend at Vanderbilt gave him a nudge. The man who would forever change how we regarded picture taking bought his first camera, a Canon Rangefinder-35mm.

And what if he hadn’t? It’s likely that Eggleston would have picked up another camera at some other point, as he was and is possessed of a curious mind, one with a love of art and craft and beauty and a need to try everything that piques his interests. Photography would have come along sooner or later. He once told Interview magazine that as a child he’d play the piano in his house every time he walked by it. His love of music, both listening and performing, continues to this day. He’s also a student of sound engineering. And radio astronomy. And guns.

Winston Eggleston

Winston Eggleston

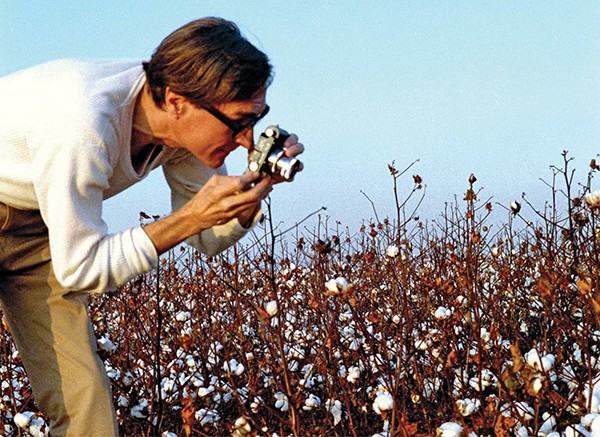

William Eggleston at work, early 1990s.

But that affair with the camera launched him on a journey that has led to the highest of praise in the art world, although not without plenty of critical drubbing, particularly at the start of his career.

Virginia Rutledge, director of the Eggleston Art Foundation, referred to the time when Eggleston was gaining wide attention for his color photographs, notably in the 1976 solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “It is difficult to imagine now, but at the time, some of his subject matter was seen to be as shocking as using that intense color in ‘art’ photography,” she says. Rutledge refers to critics who were getting the vapors over the show: “What was the point of these banal subjects in this color aesthetic that looked more appropriate to commercial advertising? Painting may have gone through several formal revolutions, but not everyone was ready for photography like this.”

The naysayers used “banal” as a pejorative but failed to understand that the everydayness of the subject matter made it widely recognizable. Add to that Eggleston’s eye and his use of color, and the photographs go beyond mere snapshots and allow viewers to construct their own story from the familiar scene.

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Courtesy the Eggleston Art Foundation and David Zwirner, New York, London, Hong Kong, AND Paris

Type C print

“It’s a natural way of seeing,” Rutledge says, “but Eggleston was a real pioneer in making it visible.”

And since that breakthrough show in 1976, Eggleston’s work has influenced photographers, filmmakers, storytellers, and artists of all kinds.

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Courtesy the Eggleston Art Foundation and David Zwirner, New York, London, Hong Kong, AND Paris

Dye transfer print

Eggleston, at age 80, is certainly one of the region’s best-known artists. And though it’s not difficult to find his works, there has been no local place devoted to his works and interests. Around 2011, a group of patrons started a discussion of creating such a facility, a museum to celebrate the artist’s work and showcase Memphis as an arts center. That particular effort didn’t pan out, but the conversation had been started and eventually Eggleston’s family — Winston, Andra, and William Eggleston III — formed the Eggleston Art Foundation and brought on Rutledge — an art historian and intellectual property lawyer — to helm it. She’s involved and well-connected in the art world, having been a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and vice president and general counsel for Creative Commons.

The purpose of the foundation is to preserve, protect, and promote Eggleston’s legacy of work and maintain the archive. But there’s no interest in simply having a shrine to the photographer’s work. The vision is broader than that. Having conversations with other people who have their own passions has been an essential part of Eggleston’s life. To this day, he has a stream of visitors who come to discuss a wide variety of topics.

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Courtesy the Eggleston Art Foundation and David Zwirner, New York, London, Hong Kong, AND Paris

Dye transfer print

And it’s that wide curiosity that the foundation wants to explore, certainly with exhibitions of Eggleston’s works, but also including other artists and a variety of events — music, film, performance, lectures.

“We want to be responsive,” Rutledge says. “Not to be driven by public opinion or requests, but to be ready to respond to opportunities to connect, and to help create those opportunities where we can. We love what we see with Crosstown Arts and the way that they are located in the kind of space that allows people to take in art as part of their daily routine. We’re interested in connecting Eggleston’s work to a broad creative community.”

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Courtesy the Eggleston Art Foundation and David Zwirner, New York, London, Hong Kong, AND Paris

Dye transfer print

The foundation is headquartered in a building on Poplar across from East High School, and the hope is to use that space as a center for the planned activities. But there will also be partnerships with other institutions, such as the public library and other art organizations.

The first exhibition under the auspices of the foundation opens January 26th at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens. “William Eggleston and Jennifer Steinkamp: At Home at the Dixon” has two groundbreaking artists — Steinkamp is an internationally acclaimed artist who works with computer animation — to display works related to core Dixon themes: floral, garden, and still life works.

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Courtesy the Eggleston Art Foundation and David Zwirner, New York, London, Hong Kong, AND Paris

Type C print

One of the Dixon’s paintings ties the exhibit together. A Memory by William Merritt Chase hangs in the Dixon Residence Living Room. The 1910 work, as described by the Dixon, “depicts a woman seated in a genteel domestic interior opening onto a sunlit Italian garden.”

Dixon director Kevin Sharp met with the foundation and says their first conversation was a success. “I told them that photography is something that we don’t have a lot of,” he says. “We like photography and we’ve done photography shows here and we’ve done shows that have elements of photography, but we don’t have a lot of expertise in the area. So we felt partnering with the foundation would be very high on our priority list.”

Koto Bolofo

Koto Bolofo

Jennifer Steinkamp

Discussions continued regarding having Eggleston’s works at the Dixon. “It wasn’t long after that that Virginia made the suggestion that we involve Jennifer Steinkamp who’s an artist I’m crazy about,” Sharp says. “I love her work, and we’ve had her work on view. So it all came together pretty organically, and we’re very excited about what it’s going to do for us.”

Rutledge was taken with the idea of having the Chase painting anchoring the show. “Bringing in work with similar themes emphasizes the fact that you can see beauty in very different ways,” she says. “Eggleston’s work on view is a combination of some of his virtually unknown and some of his best known images. There are two images of women that are just knockouts, gorgeous in unexpected ways.”

There are also Eggleston’s remarkable still life photographs. Not all are, as Rutledge observes, what you usually see at the Dixon. One such image is a 1978 photograph of a pot with flowers. “Much of the floral arrangement looks artificial, and it’s definitely bedraggled, crammed in a straw basket sitting in a banged-up terracotta pot,” she says. “But it’s beautiful. The colors are ravishing.”

© Jennifer Steinkamp

© Jennifer Steinkamp

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and greengrassi, London

Steinkamp is also a pioneer in her art, Rutledge says. Like Eggleston, who transformed his photos by using commercial color technology, she uses animation, a medium that still is more generally understood as being reserved for commercial uses, such as in Hollywood movies. “Instead, she’s using these computer animation tools in an art context,” Rutledge says. “All Steinkamp’s work in this show happens to use floral imagery. People often comment that her imagery is hyper realistic. But what’s fascinating is that the work is not based on anything imaged from the real world in terms of photography. Her flowers are entirely made from code. She doesn’t start with any pre-existing imagery, instead she programs the computer to generate what she sees as an artist.”

Steinkamp is an accomplished gardener, Rutledge says, and knows her botany. “She describes in code the look of a particular flower, but that’s only the start of the process. Because her works exist and move in a 3-D space, she also has to set rules that describe weight, the effects of gravity, of wind, the source of light. All those ‘recipes’ then ‘cook’ in the computer for several hours while the graphics are rendering.”

Steinkamp’s work can also have subtle political overtones, such as the work in the show titled Ovaries. “We see flowers and vividly colored seed-bearing fruits — literally plant ovaries — whirling around in a sky-blue space, but continually being caught up, flattened against what appears to be the window of the screen. You can read this as the artist’s comment on constraints that can still exist on women’s control of their own bodies. There’s a poignant parallel perhaps to the imagery of the Chase painting,” Rutledge says. “Although it is a gracious and priveleged setting, we know because of the time and her social milieu the woman depicted had a confined sphere in life.”

Rutledge sees both artists advancing narratives that are tied to the cycle of life. Still lifes often show some aspect of mortality and Eggleston’s photographs, whether a funeral urn or everyday tree tops, suggest a certain mystery, as do Steinkamp’s floating, nebulous flora.

With the foundation’s debut event at the Dixon, Rutledge and the Eggleston family are hoping to follow with additional significant contemporary arts programming in the city.

“We want to be involved in sharing what Memphis is all about to the rest of the world. We want to offer greater access to the range of Eggleston’s work here in the city. And we know that will be a draw as well for many people who may not know about the strong visual art scene that is already here. And once they’re in town, they’ll also see the Dixon, Crosstown Arts, Brooks, newer spaces such as the CMPLX. It’s an amazingly good time to see art in Memphis and we’re excited to be part of it.”

Spring Forward

The Dixon Gallery and Gardens is bursting with shows. The Eggleston/Steinkamp exhibition is the fifth to open in two weeks, and all are as different as they can be.

“Lawrence Matthews: To Disappear Away: Places soon to be no more”

Through April 5th at Mallory/Wurtzburger Galleries

“Under Construction: Collage from The Mint Museum”

Through March 22nd

“Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman”

Through March 22nd

Kong Wee Pang in the Interactive Gallery

Through March 8th

“William Eggleston and Jennifer Steinkamp: At Home at the Dixon”

January 26th through March 22nd