Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack

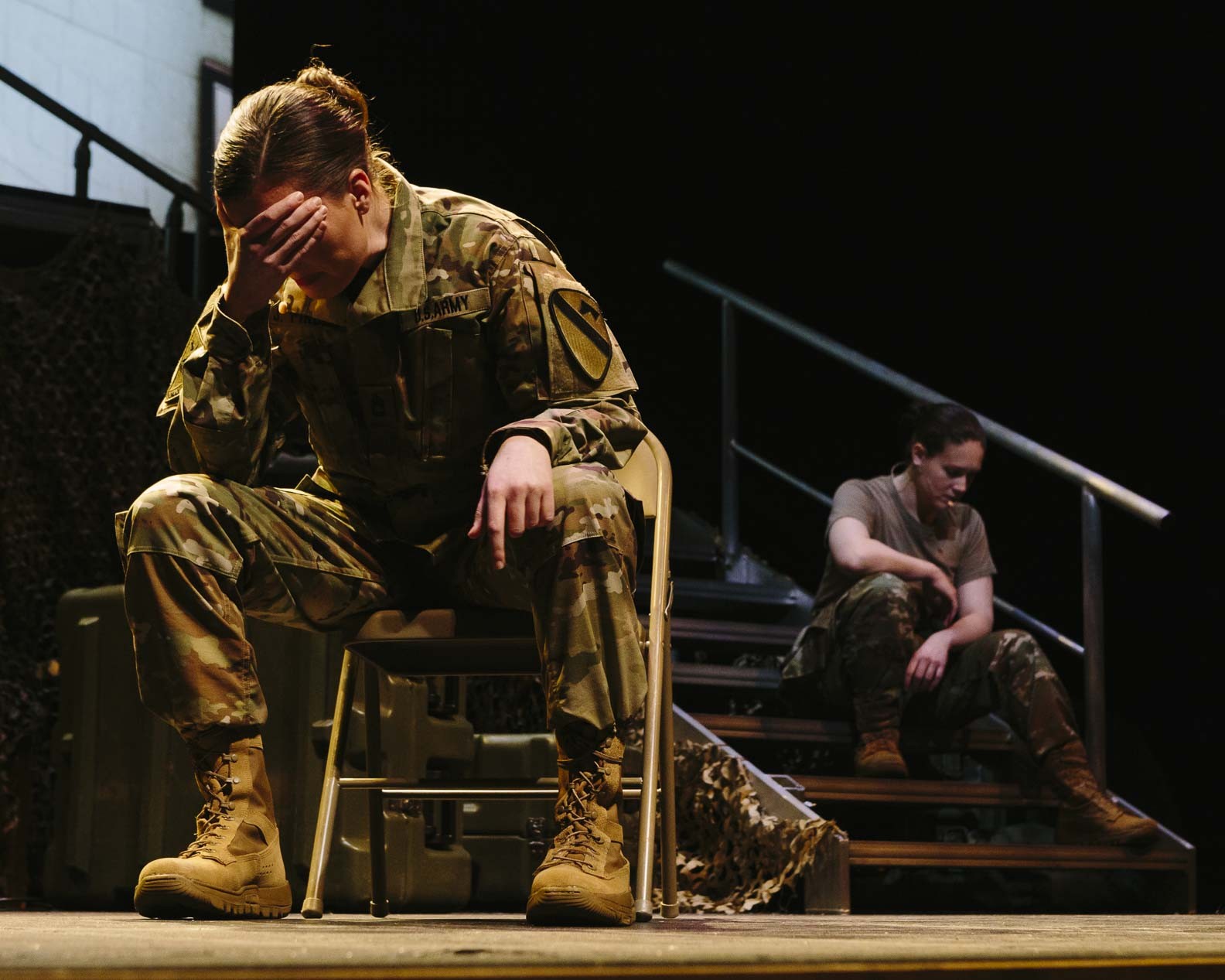

Stephanie Doche (left) and Chelsea Miller

When America has gone to war, there typically has been a national sense of purpose and involvement. Even if the engagement was controversial, as with Vietnam, there was passion. Today’s drawn-out wars seem to inspire little more than a collective shrug. It surely is a combination of several factors. The nation is not exhorted to buy war bonds, or save metals, or send books to our warriors. The casualty count has been relatively low and our troops are superbly trained and capable, so there’s little national sense of urgency. The enemy is amorphous, and so is our patriotic rage. And there are a comparatively smaller number of troops involved — how many people do you know that are in a combat zone?

But our soldiers still die, get wounded, are permanently injured, go insane, commit suicide.

On occasion, there are efforts to break through the apathy and remind us of the profound seriousness, efforts, and sacrifices of those who wear the uniform. One such is a superb work being staged by Opera Memphis during its Mid-Town Opera Festival, which began last weekend and concludes this weekend.

The Falling and the Rising is a sublime opera that distills the complexity of our wars into vivid portraits of the women and men who continue to fight them. It is a beautiful work, deep but not heavy, a one-act that packs in a lot.

The libretto is by Memphian Jerre Dye, now a Chicagoan, but Memphis lays its claim to his remarkable talent as an actor, writer, and teacher. I daresay there aren’t many operas that have passages such as: “A parachute that’s poorly packed ain’t really worth a pile of shit.” And “I’m a grown-ass women.” Along with references to propofol and midazolam. But Dye’s verbal forays pack an indelible punch in telling the story of a soldier who is seriously injured when a roadside IED goes off. The military doctors induce a coma to help the chances of her recovery. The liminal dream space she inhabits brings her face to face with others who are serving or who have served, and the telling of their stories elevates the understanding of the soldier as well as the audience.

Zach Redler is the composer and deftly brings together various influences to beautifully express the story. The text is paramount, he says, as he speaks of what supports it: bluegrass, of black gospel music, Debussy’s Clair de Lune, and dollops of Sondheim. It is tonal with leitmotifs for the distinct characters that further sharpen their definition.

And the characters are beautifully rendered in the libretto and performed with remarkable power and grace by the singers. The Soldier is Chelsea Miller, former artist-in-residence at Opera Memphis, and possessed of an expressive soprano voice.

Mezzo-soprano Stephanie Doche is explosively eloquent as Toledo, the tough-as-nails “grown-ass woman” who reveals her past to the Army psychiatrist. As the parachute instructor Jumper, the popular tenor Philip Himebook brings a mix of kindness and swagger to the role. Darren Stokes, a bass-baritone, sings the part of the Colonel, grieving over the loss of his wife in action with exquisitely rendered restraint and feeling. The final character to appear in the Soldier’s dreams is the Homecoming Soldier sung by Marcus King with elements of rage, sardonic wit, humility, and reluctant acceptance, expressed at his hometown church where he keeps himself in check because his mother is there. But you can’t miss how he seethes, copes, and shares his wheelchair-bound fate as he embarks on this new life he never chose.

The Dye-Redler opera would have been complete with the original finale, but director Ned Canty, general manager of Opera Memphis, added a genius touch. He enlisted 24 veterans and active duty military men and women to be the chorus of the opera. When the five principal singers were bringing the performance to a close, it was already emotional, but then, as the two dozen chorus members walked slowly out joining in — some in dress uniform, some in POW T-shirts, some in fatigues — it became larger, deeper, something of a higher mystery and resolution. And an ideal conclusion to a brilliant performance.

The Falling and the Rising performs April 12th and 13th at 7:30 p.m. with members of the Memphis Symphony Orchestra playing. Tickets: www.operamemphis.org/tickets or call 257-3100.