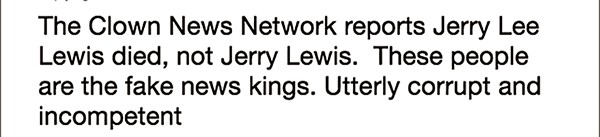

The passing of the great Jerry Lee Lewis last Friday, at the age of 87, has brought floods of memories rushing back for those who knew him. As drummer J.M. Van Eaton posted on social media, “He was the greatest entertainer of them all. A musician’s musician. So lucky to have played on his early Sun recordings.”

That quote alone pinpoints what made Lewis stand out among the other stars of Sun Records: his virtuosity. True, The Prisonaires, Elvis Presley, and Roy Orbison had golden voices, and Carl Perkins was no slouch on the electric guitar, but both “Jerry Lee Lewis And His Pumping Piano,” as he was billed on his early Sun singles, were equally dazzling.

“He could play anything with ease,” recalls Jerry Phillips, son of Sun Records founder Sam Phillips. “He could sing any song, ‘Over the Rainbow’ or ‘Old MacDonald Had a Farm,’ it didn’t matter.” Nothing expresses that better than the album Jerry Phillips recommends to anyone hankering for some prime Jerry Lee: The Knox Phillips Sessions, a little-noticed recording date from the ’70s that was not released until 2014.

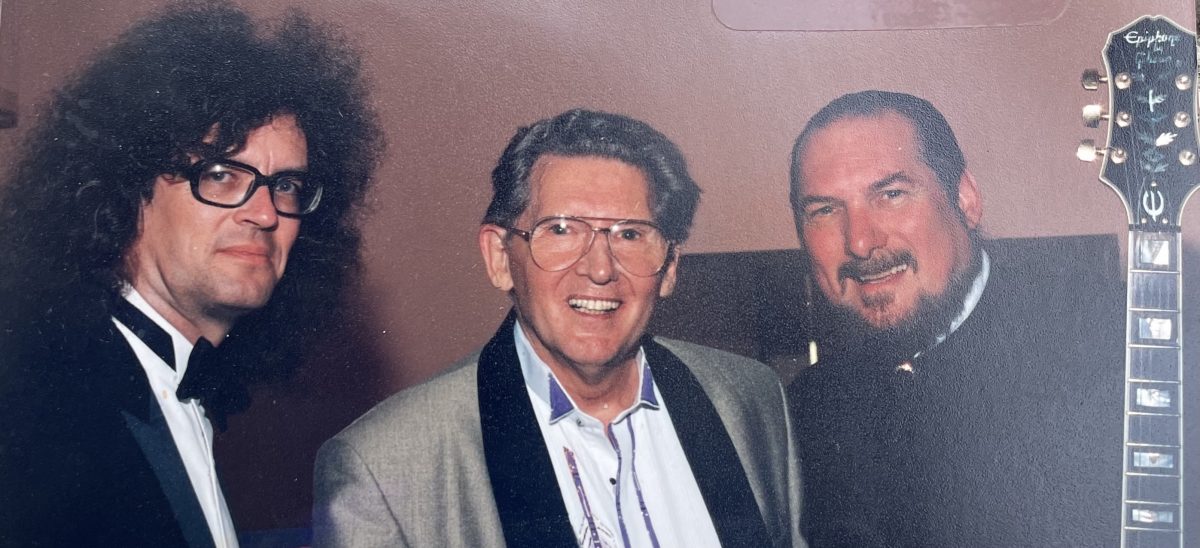

Phillips’ words took me back to my first encounter with the Killer in the late ’80s, sitting cross-legged on the dance floor of Hernando’s Hide-A-Way, at the foot of the piano. Hearing Lewis sing, “Somewhere over the rainbow …” then ad-lib, “there’s a place Jimmy Swaggart only dreams of” as a dig at his more pious cousin, will be forever burned into my cerebrum. And that’s precisely the irreverent energy present on The Knox Phillips Sessions. Lewis’ irrepressible talent and ferocity are on display there, thanks to the hands-off production of Jerry’s late brother Knox.

“It was a time when Jerry Lee was out of his contract with anybody,” recalls Phillips. “He came to the studio and Knox was engineering, and we just started the tape machine and let him go. It was a very interesting trip. And it’s all on tape: He takes to the piano and goes, brrrring! Then he says, ‘The pills just hit!’ and takes off playing ‘Meat Man.’ He’d want to go to the strip club about midnight, so we’d all jump in his Rolls-Royce and go there, and then come back and do some more recording. Of course he wasn’t sleepy, you know what I’m talking about?”

Like his father before him, Jerry Phillips tells it like it is, and so does this album. Phillips notes: “I told Knox, ‘Sam cut the first great recording of Jerry Lee, and you cut the last one to really capture the man.’” Hearing the album today, it’s striking that such an unhinged moment was recorded as it was, without filters or editing. For it perfectly captures Lewis the artist-as-provocateur and all the multitudes he contained, from the sanctity of “Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior” to the much lewder sentiments of “Lovin’ Cajun Style” to those electrifying moments where he indulges in an eerie falsetto.

At that point in his life, Lewis was feeling reflective, even as he reveled in the wild hedonism of Memphis in the ’70s. He turns “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” into a tribute to himself: “My name’s Jerry Lee Lewis, piano playing motherhumper, country and western motherhumper, just a plain motherhumper when I take a notion. … I seen a cat down at Fridays. Picked a little fight with him. He broke my nose, I had a hold, and I whooped the shit right out of him. They call me bad, bad, bad, the Killer! Meanest man in Memphis, Tennessee!”

Indeed, at times it seems Lewis is writing his own elegy, as when he mulls over the death of songwriter Stephen Foster in “Beautiful Dreamer,” introduced on the album by an unidentified narrator. “Thanks, Stephen, Al, Hank, Jimmie, and Jerry Lee,” intones the voice, invoking Lewis’ late heroes, Stephen Foster, Al Jolson, Hank Williams, and Jimmie Rodgers, as if Lewis had already ascended to heaven. Then the Killer chimes in again: “Lost in the arms of life’s raging sea, neighbors … you’d better think about it. God bless you.”

A service for Jerry Lee Lewis will be held on Saturday, November 5th, at Young’s Funeral Home in Lewis’ hometown, Ferriday, Louisiana, with the visitation at 10 a.m., the funeral at 11 a.m., followed by a public celebration of his life at the Arcade Theater.