Jim Adcock wants you to know that he’s not here to point fingers. But he also wants you to know that Memphis has more than 1,500 homicides that are unsolved. Also, he wants you to know that he is here to help.

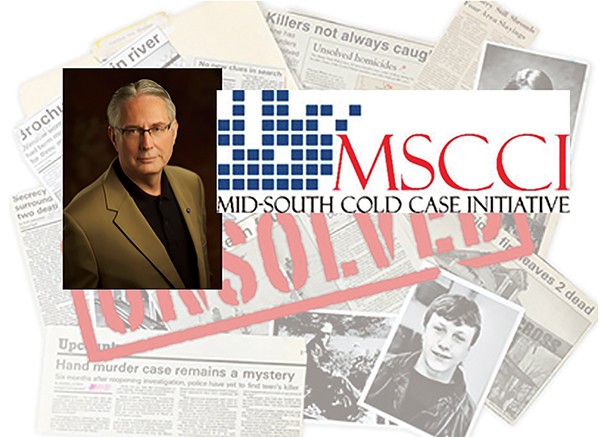

Adcock served for more than 20 years in the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command, was a coroner in South Carolina for a time, taught criminal investigation at the University of New Haven, and is wrapping up work on a best practice guide with the National Institute for Justice (NIJ) Cold Case Working Group.

He’s in Memphis now and has established the Mid-South Cold Case Initiative. The nonprofit is designed to provide funds like grants to local law enforcement agencies to fuel cold-case work here. — Toby Sells

Memphis Flyer: How bad is the problem?

Jim Adcock: Nationally, there are over about 242,000 [unsolved murders]. So, Memphis is a small drop in the bucket. But Memphis, in the last five years, has had some problems, a rise of cold cases. That’s due, primarily in my view with my expertise, to a lack of manpower and lack of funds. They’re not doing anything wrong; they just can’t.

MF: So, you’d offer them money?

JA: They’d have to request it and justify it. They would have to have a dedicated unit, and they’d have to be sincere in [what] they’re doing. I’m not just going to write a check arbitrarily.

It’s almost like grants. Justify what you want. I’ll run it before my board. If we all agree, then — boom — you get a check.

MF: Why is solving cold cases important?

JA: First of all, you’ve got families still out there without answers. Are you just going to tell them that they don’t matter?

The other part of it is about getting bad actors off the street. We know they’ve committed more crimes or will commit more crimes most likely. We don’t know that 100 percent. But the odds are, they are going to continue. That’s costing [law enforcement agencies] money, too, because [they] have to respond to these crimes.

MF: How does a murder case go cold?

JA: [Murders go cold] when it reaches a point where there’s no more viable leads that [investigators] see in the file. Then, it sits in a shelf or a bookcase until something pops up.

Then, over time, they get a little crusty, a little dust on them. Then, more cases are added [and are prioritized]. Now it becomes, “I’m too busy to get that because I’m onto this now.” It’s a problem we all have.

MF: What would solving some cold cases do for Memphis?

JA: It should restore complete confidence in law enforcement, save money, see that justice is served, and provide families with answers. It will also cause [people] to come forward more often to talk.

The other side of it is, if this all works, I’m going to write about it where Memphis could become “the model” for others to follow. It’s like a business plan test — it either works or it doesn’t. If successful, the initiative can be applied in other jurisdictions.

More about the MSCCI at www.ms-coldcaseinitiative.com