On Sunday, July 14th, the Premiere Palace hosted a memorial service for the late Sturgis Nikides, best known locally as the virtuoso blues guitarist in the Low Society, who passed away last April. Gone far too young, he managed to pack several lifetimes of experience into his 66 years, growing up in Brooklyn, New Jersey, and Staten Island, then ultimately falling in with Manhattan’s alternative music scene. Those familiar with the film Who Killed Nancy?, about Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen, may recall Nikides’ on-camera recollections of his days living in the Chelsea Hotel on the same floor as Vicious in 1978, including the night of Spungen’s murder.

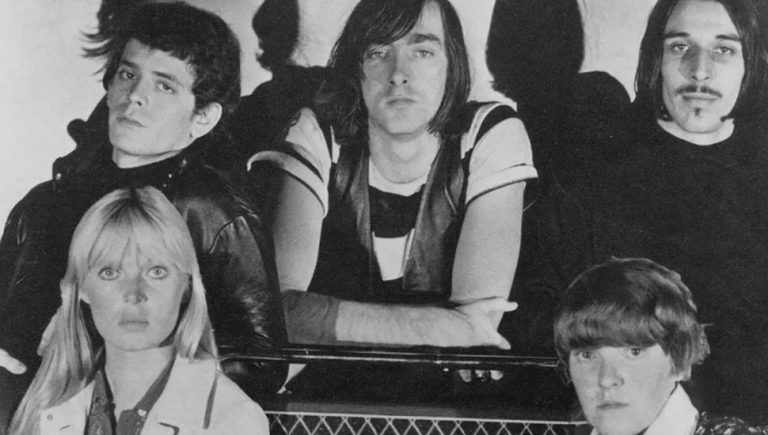

During that era, by the time he was only 19, Nikides distinguished himself as a guitarist for John Cale, who’d long moved on to a solo career after his time with the Velvet Underground. At last Sunday’s memorial, that era of Nikides’ life was well-represented by the singer-songwriter deerfrance, who played a short set with a band that included her bassist Kai Eric (erstwhile member of Tav Falco’s Panther Burns) and two local players (Lynn Greer on drums and myself on guitar and keyboards).

During the set, deerfrance spoke wistfully of getting to know Nikides when they both played in Cale’s band from 1979-1981. Indeed, the guitarist was nicknamed “Hellcat” in the credits to Cale’s 1981 album, Honi Soit. That album was Cale’s greatest commercial success, making it into the Billboard 200 that year.

Yet the bulk of those in attendance were Nikides’ Memphis fans and friends, who were most familiar with Low Society, the dynamic band he and his wife Mandy Lemons formed in 2009. Jeff Janovetz, DJ for the online Radio Memphis, gave a heartfelt remembrance of his encounters with Nikides, followed by Brad Dunn, who recalled the power of hearing Low Society for the first time and his efforts to book the band at American Recording Studio. This ultimately led to the band’s second album, released by Icehouse Records/Select-O-Hits in 2014, You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down.

That made it all the more powerful when Lemons joined deerfrance’s band for a passionate rendition of Tom Waits’ “Way Down in the Hole.” In what was clearly a cathartic moment for the singer, she had the audience spellbound. Afterwards, I caught up with Lemons to learn more of her and her husband’s story.

Memphis Flyer: How did you and Sturgis meet?

Mandy Lemons: It was in October of 2008, in New York. A good friend of mine had known Sturgis for thirty years or so, and he was already trying to hook us up musically. Like, ‘Oh, you need to meet this guitar player!’ and telling him, ‘You need to meet this singer!’ So he had a party at his house and we met and I was just like, swept away immediately. But I had to play it cool for a while. You know what I mean? He had no idea that I was that in love with him! Then, after playing music for a year, we got to know each other and became friends. And then we dated for a year, and then we got married.

How did you two wind up in Memphis?

We had our first European tour at the end of 2012. And after that, I wanted to go down south and roll around a little bit, you know, and take him down there and get into Texas blues. Everyone’s a badass down there, you know, and I’m originally from Houston. So we went down to Texas and kicked around for like four months, but we just couldn’t find a place to live, we couldn’t find a good drummer or bass player. And then we played the Juke Joint Festival [in Clarksdale, Mississippi], as a duo.

My friend, who was kind of like our patron at the time, said, ‘You know, Memphis is right around the corner. You guys should go check it out.’ And we were like, ‘Oh, we didn’t think about that. Really?’ So he put us up for a week here, in an AirBnB, and everything just went right. So we got our stuff in Texas and came back here and have been in the same apartment ever since.

And you connected with the scene here rather quickly, it seems.

On our first night here, we saw Earl the Pearl play at Huey’s. And we were just like, ‘What?’ Like, ‘We’re home. We’re in the right place.’ And the next night, there was an open blues jam at Kudzu’s. So we went over there, and of course they made us wait till the very last, because we looked like a couple of New York freaks, which is what we are! They were like, ‘These people are either gonna really suck or they’re going to be great.’ So we did our best, and everyone loved it. People came up to shake Sturgis’ hand immediately. Me and Dr. Herman Green connected, and we played on Beale Street the next night, which had been a dream of mine since I was 12. And I just was blown away.

Low Society was so well regarded after that point, and many fondly recall your residency at the fabled Buccaneer Lounge back in the day. You made your second album at American Recording, and released a third album as well. Are there any unreleased tracks by Low Society that you were working on while Sturgis’ health was failing?

Well, you know, he started having health issues when Covid started, and had open heart surgery last summer, and that’s when it started getting scary serious. Then he got this crazy, aggressive, super fast cancer that killed him in two months.

So that was on and off for the last four years. He would get better and then something else would happen. But in the good times, when he was feeling good, he definitely was playing guitar. I mean, it’s like being an athlete. You have to give back, because if you don’t consistently use it, you lose it. So he was practicing, and we had our fourth album in the works. He was producing that and mixing it and putting in his magic sauce and overdubs and all that stuff. And he finally finished it just a few months ago, and he said, ‘That’s it! It’s finished.’

All I’ve got to do is lay some vocals down and get it mastered and distributed and all that stuff.

Was it also cut at American Recording?

No, actually, we recorded all of it in Belgium. Our drummer and bass player live there. But it’s been like five years, since 2019, since Sturgis and I played a show. So thank you guys so much for having me up there [at the memorial] and allowing me to sing with y’all. That was really cool and very much needed. It’s been a long time. But…there’s more where that came from.