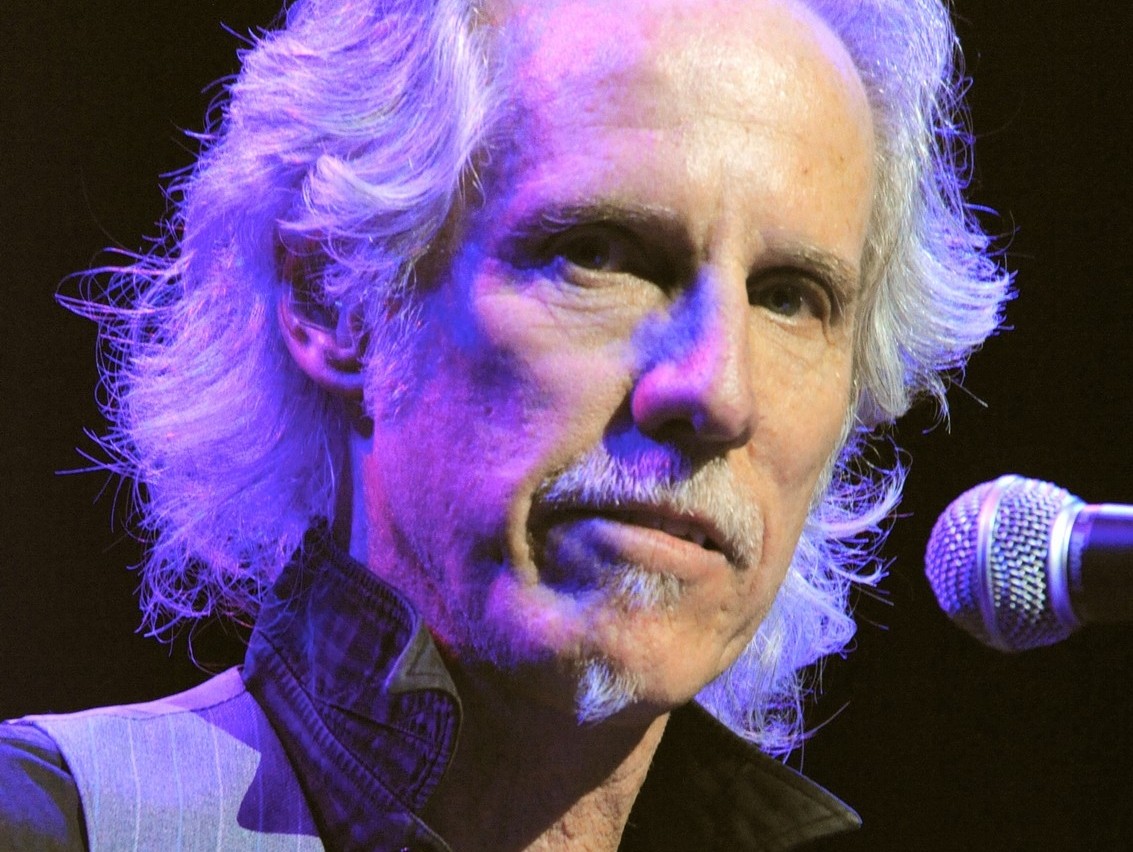

This week the Memphis music community was dealt another tragic blow with the death of Bob Holmes on October 16. Holmes, the lead guitarist and songwriter behind one of the city’s foundational punk rock bands, the Modifiers, as well as Angerhead, Sarah & the Eyes, and the Binghamptons, had been in declining health in recent months due to a variety of illnesses, including cancer. He was 64.

Those closest to him (myself included) were not entirely shocked when the news broke, as Holmes was unable to make a scheduled appearance with the band at B-Side for the Antenna Club historical marker dedication event earlier this month. The Modifiers even played the venue when it was known as the Well. Behind the scenes, Antenna founder Steve McGehee told me that one of his primary motivations for putting it on was to give Holmes one last chance to perform and visit with friends, but alas, it wasn’t meant to be.

“I swear to you, Bob inspired the whole thing,” says McGehee. “That was my main goal, getting him to play again. It’s sad that it couldn’t work out.”

It’s hard for me to put into words just how important Bob Holmes was to the Memphis music scene. Bob (I’m just going to call him “Bob” from here on out), lead singer Milford Thompson, and their rotating cast of Modifiers poured their sweat and souls into every performance, breaking ground and opening doors for every original punk/alternative band in this town that followed along the way. The band’s reputation for both hi-jinks and debauchery was legendary, but Bob was every bit as prolific and accomplished as a songwriter and musician as he was a creator of spectacle. And make no mistake about it, even up to the end, Bob could still play a mean guitar. Here’s the last live version of the Modifiers: Bob, Terrence Bishop, John Bonds and myself – but mainly Bob – tearing it up on the now defunct Rocket Science Audio podcast:

In Memoriam: Bob Holmes, Memphis Punk Pioneer, Dies at 64

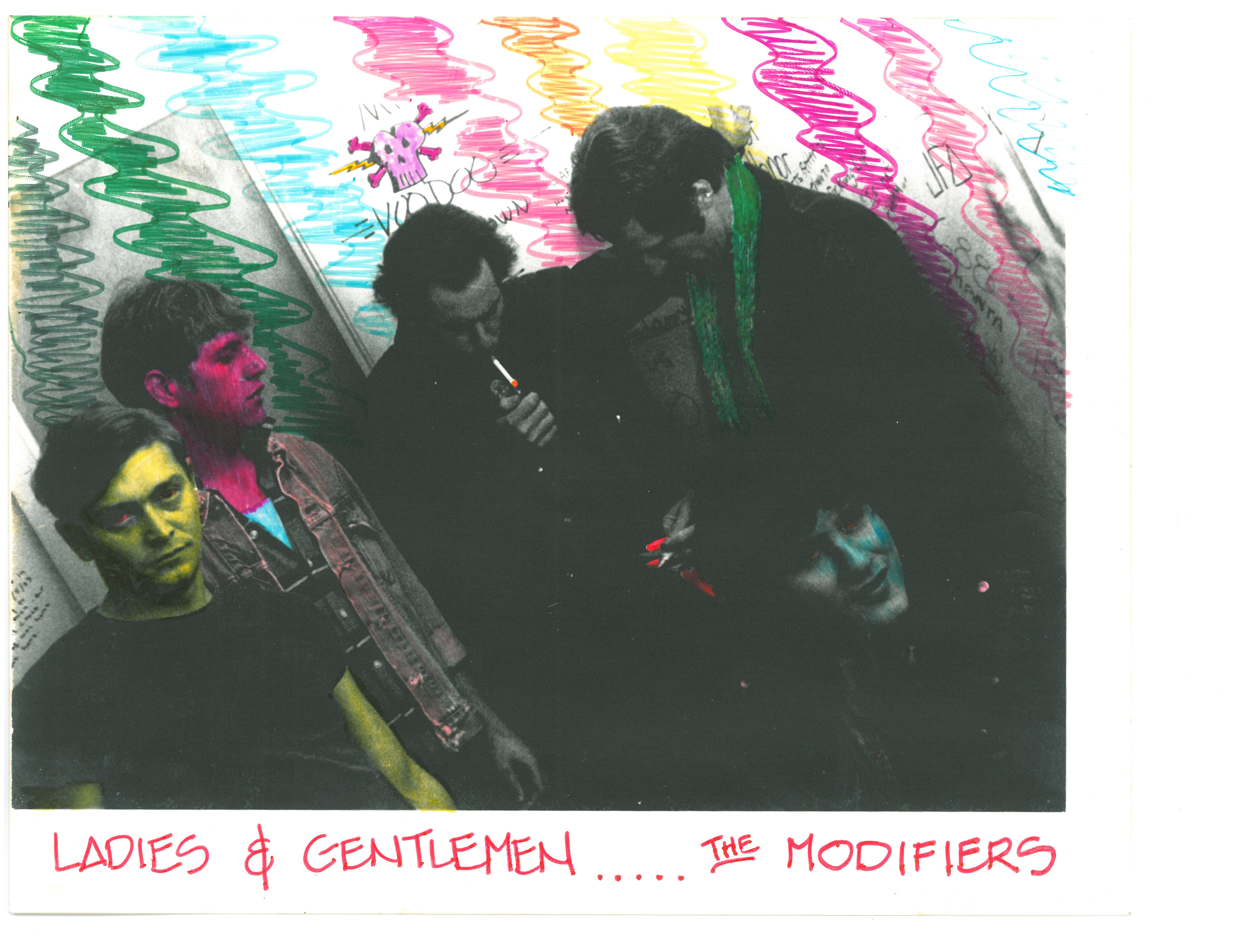

Over the course of the band’s roughly 35 year history, the Modifiers line-up ebbed and flowed as they bounced back and forth between Memphis and Los Angeles, and members – including the famous ones like the Doors’ John Densmore, Fear’s Derf Scratch, and Big Star’s Alex Chilton – came and went quickly. But one constant was the understated brilliance of Bob Holmes. And you don’t just have to take my word for it.

“I’ll never forget meeting Bob at the Well,” says David Catching, producer and guitarist for groups like the Eagles of Death Metal, Queens of the Stone Age, earthlings?, and the Modifiers. “He and Alex Chilton were my first guitar heroes I could actually talk to.”

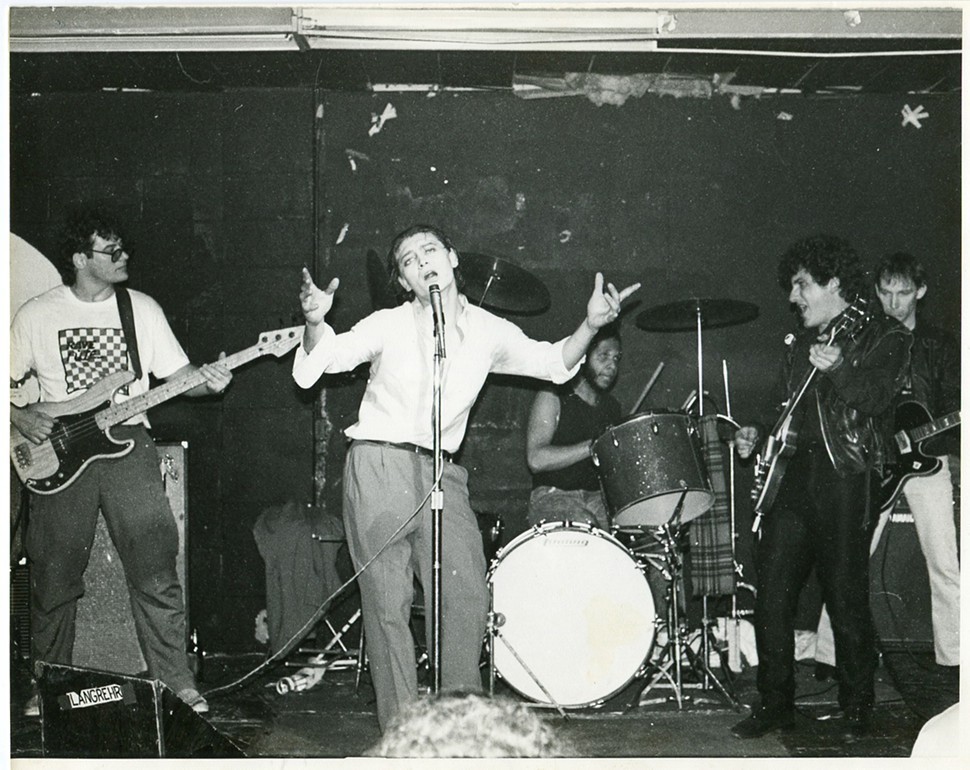

The Modifiers at the Antenna, early 80s: Bob Holmes, second from right.

Catching also posted the following on social media via his studio’s (Rancho de la Luna) twitter account: “I played with the Modifiers from 1979-1989. Bob Holmes Ohm and Milford Thompson showed me some of the greatest times of my life and taught me more about life and living than anyone. I wouldn’t be what, or where I am without them. Love always. RIP”

“Bob, was one coolest cats around,” says Chuck Roast, former Modifiers and Suburban Lawns drummer. “Quiet, strong opinions, very talented guitar player, could shred on punk and the next minute lay down some sweet heavy blues. It was great time playing with him and Milford.”

“Milford was the method actor up front, but Bob was the engine. He was the musical director,” says Ross Johnson, drummer with Tav Falco’s Panther Burns and the Modifiers, among others. “He had a tone like no one else had, I could never figure it out. Like most signature players, like Chilton or Teenie Hodges, the sound came out of his fingers. It didn’t matter what guitar he was playing on, it was the sound of Bob playing. That made him very unique.”

The Modifiers

“He was an unbelievable, out of this world guitar player. Like no other,” says John Bonds, drummer with the River City Tanlines, Subteens and Modifiers. “It was an honor and a privilege, not just to be in the band but to become friends with Bob and be a part of his circle.”

I could quote a dozen more friends and bandmates, and they would all say the same thing: Bob Holmes was and is a wildly underappreciated figure in Memphis music history, and it’s a shame he’s gone.

As for me, I’ll certainly remember Bob as a brilliant musician. As I’ve written before, he was an inspiration and mentor to me as a young guitarist. But my favorite memories of him are of us just hanging out, winding up my dad for kicks, making fun of bad television, or posing ludicrous questions to my cats. (“Are you a cat?”). He was a good, fiercely loyal friend and I valued the time that we got to spend together.

The music of Bob and Milford and the Modifiers is very important to me, and collecting as much of it as I could consumed much of my last few years in Memphis (my wife and I relocated to Chicago in 2017). There is a vast catalog of unreleased material, and I’m hopeful it will get released sooner than later. It’s long overdue. Until then, here are two things I uploaded (with help, thank you Fred Kelly) to YouTube this afternoon to tide the world over:

1. The rarely seen/heard A-side to the Modifiers only official release, and arguably the band’s most famous song, “Roweena.” The rock stars play on this one.

In Memoriam: Bob Holmes, Memphis Punk Pioneer, Dies at 64 (2)

2. The world premiere of “Peasant,” a song Bob and I “wrote” and recorded in my living room when I was 14 using my Casio keyboard. I have only played it for two other people before this publishing. It’s pure Bob.

In Memoriam: Bob Holmes, Memphis Punk Pioneer, Dies at 64 (3)

RIP, my friend. Your music will live on, I promise.