High school civics and Political Science 101 were never like this.

“You know, and that just how it works, I mean you don’t come out, out of the Senate with 17, yo’ shit don’t fly. If you don’t come out of the House with 51, yo’ shit don’t fly.”

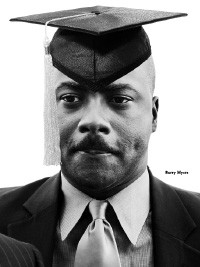

That’s Barry “Bag Man” Myers lecturing to undercover FBI agent L.C. McNeil on the arithmetic of passing legislation in the 99-member House and 33-member Senate in Nashville. Crude, you might say, but accurate. At the Tennessee School For Scandal (TSFS), we cut through the s*** and get to the f****** point!

Tired of paying $5,000 or more each year in college tuition? Bored with pompous professors droning on about the separation of powers and a bunch of dead dudes? Looking for something more than football games and beer parties? Would you like to, in the words of adjunct instructor Myers, “make some f****** money”?

Then consider enrolling in correspondence courses at the elite U.S.-government-inspected TSFS and learn the art of the semi-hustle, the false statement, the concealed microphone, the rigged stock offering, the big juice, the sneaky non-entrapment, and the do’s and don’ts of taking a payoff. Our instructors are the best bag men, political crooks, and undercover snitches in the business. Enroll now, because when they get certified, they’ll be leaving TSFS for some of our most exclusive, uh, federal institutions, and their office hours will be sort of restricted, if you get our drift.

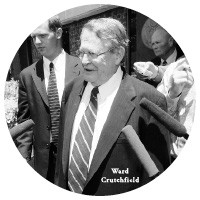

At TSFS, our graduates know how to get ahead. Myers learned from one of the best, former state senator Roscoe Dixon, who graduated from TSFS to land a $100,000 a year job with the Shelby County Mayor’s Office! (The former senator, unfortunately, will not be teaching this session, but his lessons are available in a special boxed set of tapes.) Want to go grad school? John Ford and Ward Crutchfield will show you how to make lots more than $100,000.

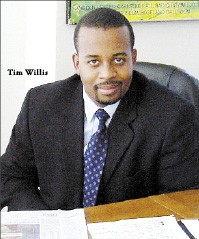

At TSFS, all of our lessons in the politics of the hustle are available on audiotape, and if you enroll now, you can even get a free black-and-white videotape of an actual payoff shot by master cinematographer Tim “Tape Recorder” Willis! Meanwhile, here’s a sample of our latest offerings.

Methods of Political Upward Mobility 101:

Students will get an overview of opportunities in the public and private sector. No experience required. Instructors Barry Myers and L.C. McNeil of E-Cycle Management demonstrate basic techniques in this snippet from May 2004.

Myers: “Oh man. I wish I could come on y’all’s payroll, but see, like I say, the only thing is that, in three months, I mean this shit’ll be over with and I’ll be a public official, and I couldn’t be on nobody’s payroll and shit. But then, I figure like this. I still be able serve ya’ll some good, ’cause if I’m the senator, hell, I still can introduce the same shit that Roscoe’s on, you know, carry on.”

McNeil: “Right. That’s where it, that’s where it gets lovely for everyone because, you know, you get this thing flowin’ like a fine-tuned machine.”

introduction to government work 101:

Introduction to Government Work 101: You can’t eat your way to prosperity. Sure, there are lots of parties and free food, but being a legislator has a downside too, as we see in this session with Roscoe Dixon and L.C. McNeil in August 2004.

Dixon: “I don’t know. I just need to get in the big leagues, man. You know we knock around, you know legislators, we don’t make no money, man.”

McNeil: “Really?”

Dixon: “Sixteen thousand.”

McNeil: “How you make it off of that?”

Dixon: “I don’t know. It must be the man upstairs. You put your office allowance in there, you might get to 23. Per diem, may get to 27. You got to spend most of that per diem, you know, hotels and stuff like that … Man, you be lucky you can clear 30.”

McNeil: “Right.”

Dixon: “Ah, everybody, everybody got some semi-hustle, ah, goin’ and, ah, this would be a hell of a opportunity, ah, cause really you’d be controllin’, ah, county government, I mean operatin’ and runnin’ it.”

McNeil: “Okay, explain it to me ’cause I get, I get lost in the shuffle. I’m thinkin’, you know, unless you goin’ to be governor you can’t get no better than bein’ senator, right?”

Dixon: “Of yeah, you can get better. People don’t know that ’cause this will be operational, I mean you be operational, I mean, physical documents coming across your desk.”

McNeil: “Okay.”

Dixon: “Well, let’s see where we gon’ built this road. Let’s see if we gon’, ah, ah, get this contract, do this, or modify contracts.”

McNeil: “Right.”

Dixon: “I mean it’s administrative, ah, it, the position A C had talked to me about was the deputy CAO.”

(Four months later, Dixon was named deputy CAO by Mayor A C Wharton. After Dixon was indicted in May 2005, Wharton forced him to resign.)

Advanced Government Work 501:

Yes, rigging road contracts is lucrative, but the hours and paperwork can be a bitch. If you’re a lawyer, TSFS will show you how to parlay that into big money. Listen in as Chattanooga bag man and school board member Charles Love tells undercover FBI agent Joe Carson about 78-year-old senator Ward Crutchfield of Chattanooga aboard a yacht in Miami in December 2004.

Carson: “Let me ask you the other thing. I was curious. On Ward, he gets $150,000 a year from the school board? You’ve got to be kidding me. The school board has got that kind of money? Does he have that much work?”

Love: “I’m telling you, man, we spent … Let me tell you how much we spent on attorneys outside of Ward Crutchfield last year as a school district: about $500,000.”

Carson: “Why would you need to go outside of Ward if you are paying him that much?”

Love: “He doesn’t have the expertise. For example, if somebody sues the school district, which we have been sued, we get sued every month on something.”

Carson: “Oh, I’m sure.”

Love: “At one point the board is saying, why don’t we get rid of this guy?”

Carson: “Crutchfield?”

Love: “Yeah. I said why don’t you do it. I ain’t doing it.”

Carson: “I agree with that.”

Love: “Political suicide. Everybody said, well, political reasons, nobody is saying it, but it’s implied. It’s worth the $150,000 to keep him because he does go to Nashville and he has a direct link to the school board to take to Nashville to tell them Hamilton County needs this, Hamilton County needs that. It’s more of a support advocate than an attorney. Now, he will ask for an opinion, maybe every four or five months, ask for an opinion. He’s been doing that for 20 years.”

Carson: “You are kidding me? He could make a pretty good living just doing that.”

Love: “Ward Crutchfield is the kind of attorney that, if he’s your attorney and he goes into court, ain’t a whole lot of discussion, and he usually wins. You know what I’m saying? Ward has gotten guys off for murder, you know what I’m saying? They may get 10 years for first-degree murder because of who he is. He knows all the damn judges, he knows all the people in the courthouse.”

Carson: “I guess $150,000 buys a lot.”

Love: “Buying his influence more than you are buying his legal expertise.”

Carson: “That’s what we are doing basically, isn’t it?”

Love: “That’s what you are doing.”

Carson: “I guess it technically would be a conflict for him to be a state senator?”

Love: “It is. If somebody pushed it, it would be.”

Carson: “And votes on appropriations for schools.”

Love: “Uh huh.”

Carson: “Geez. You know what? Everybody has got their own thing. Good for Ward.”

Love: “Everybody has got their deal.”

Bag Man for Beginners:

This introductory course is for risk-takers who are undecided about their major. Some graduates go from politics to the FBI and the United States Attorney’s Office. And some go both ways! Feds love bag men because they’re truth tellers. Without a client, they’re nothing. As assistant U.S. attorney Tim Discenza told a jury recently, “Do you think Barry Myers would come in and lie and say he was doing something for Roscoe Dixon just to get himself convicted of a felony?” This May 14, 2004, exchange is between Myers and L.C. McNeil.

McNeil: “But see, that’s my thing. I don’t want, I like to deal with folks like yourself that are careful. I don’t want a lot of folks that’s talkin’.”

Myers: “Right.”

McNeil: “And shit like that, ’cause I don’t talk about my business. You know, the fewer the people that are involved the better. You know, when Tim first said to hook up with Barry, I’s like, well, you know, I kicked it with Barry, but is Barry cool, is he down? He’s like, Barry is cool.”

Myers: “Oh yeah. I mean I’m very loyal, man. My thing is, I’m going to protect the senator and the other legislators. That’s my job and stuff.”

McNeil: “Cool.”

Myers: “That’s jus’ the way I’m gon’ do it, because I been operatin’, carryin’ Roscoe’s money long before you and Tim come along. I was toting the money for them. Whenever somebody wants to do something they would come to me.”

Advanced Bag Man 301:

A follow-up to our introductory course, this one’s offered at our Chattanooga campus, with a special field trip to Miami! In December 2004, Charles Love discusses Ward Crutchfield with Joe Carson.

Carson: “Okay. We’ve given Senator Crutchfield, what, three or four thousand dollars?”

Love: “Three thousand dollars.”

Carson: “Three thousand dollars and other than him saying, yeah, I’ll support it, co-sponsor it, he hasn’t … I would like to see him insert that as opposed to Senator Ford.”

Love: “Okay.”

Carson: “Okay? I don’t think that’s unreasonable, do you?”

Love: “No.”

Carson: “And you can tell him, hey, for some reason it got dropped out, if it was there originally. If it wasn’t there, that’s one of our four things and you have those bullets that I sent you on why we have the … So that’s it with that.”

Love: “Okay.”

Carson: “But if you’ll talk to him as soon as you get back in, if he agrees to do it and will do it, call me and I’ll just call him and wish him a Merry Christmas, and thank him for adding that for us. Okay? I want to stay in touch with these guys.”

Stock Market Stings 301:

Instructors L.C. McNeil, Tim Willis, and Joe Carson. Learn how to talk about fake companies and snare unsuspecting lawmakers by putting dollar signs in their eyes. Plus some cool stuff about the stock market and stock offerings, as you’ll hear in this 2004 conversation between Myers and McNeil.

Myers: “So y’all thinkin’ y’all could possibly make $10 or $20 million off this deal?”

McNeil: “I’m explain to you how this works. When you start a company, if your company starts off and it has legal precedence, meaning there’s legal, there’s legislation that regulates the way business is to be done. Then, after that, you have contracts with certain individuals and certain companies that guarantee you’re gonna do a certain amount of business. Then you can go public. And once you go public, there’s so much interest in your company because, one, it’s a legalized, how do I say, business interest.”

Myers: “Okay.”

McNeil: “Then you take it a step further and you already have contracts, and it’s like a no lose. It’s like people are mandated to have to use your services. So it drives the stock prices up. You can start off with, ah, maybe anywhere from, you know, what they call a penny stock. I’ve never done like the penny stocks side. I’ve gone anywhere from 10 to 50 cents a share. Almost up to a dollar a share.”

Myers: “Okay.”

McNeil: “When I did the dot-com business, ah, music business, I did two of them. The first one was at 10 cents, the second was at 50 cents. First one, when I finished and when we pulled out of it, and it basically, I mean, it went under because all this stuff was being stolen off the Internet.”

Myers: “Stolen off the Internet, yeah.”

McNeil: “You know what I’m sayin’? But a 10 cent stock, it went to almost $15 a share. You see how much we make?”

Myers: “I don’t need to become a state senator. Shit, y’all makin’ the real money.”

Undercover Operatives 701:

An advanced course by invitation only. Students must show strong background in acting and criminal behavior. In February 2004, instructor Tim Willis demonstrates his stutter step as he tells Roscoe Dixon that E-Cycle wants “first call” on used computers. Note how carefully Willis walks the line on entrapment. Notice who suggests working through regular channels and who brings up the subject of money first! Fooled you, huh? A master at work. Or as prosecutors like to say, today’s defendant is tomorrow’s witness.

Dixon: “I mean, why do you want to be up there?”

Willis: “Oh, so they can have first dibs on all of this.”

Dixon: “You takin’ all this.”

Willis: “Right.”

Dixon: “Ain’t one or two computers comin’ outta’ here on that, first thing. I mean folks just don’t want ’em.”

Willis: “Right, I, I, I see, I see what you’re sayin’. But then what else is, you, you see what they, their, their whole intention is. The, if they can show that they have a contract with the state of Tennessee, to, to take in this, this, this is a sizeable amount. Just imagine all across the state. They could say they have a contact with the state of Tennessee where they have first.”

Dixon: “But they hadn’t, they hadn’t talked to the state of Tennessee. If you see what I’m sayin’?”

Willis: “Naw. I talked to somebody in an office that …”

Dixon: “You talked to General Services?”

Willis: “Naw.”

Dixon: “In other words, they don’t know what they’re doin’. They, they as lost as a man in the moon.”

Willis: “Uh huh.”

Dixon: “There needs to be some conversation with people who are over this … You have an orderly process. Basically, now what you can do is put a offer on the table, this is what we’d like to do. What do you think about it? And they’ll tell ya’ yea, nay, or let’s modify type of thing.”

(Dixon makes a phone call, and the conversation resumes a few minutes later.)

Dixon: “I mean, how old is the company?”

Willis: “This, this, this is a new branch of an older company. This is a offshoot. So this has only been up and runnin’, man, maybe two years. Something like that.”

Dixon: “Are they tryin’ to be national?”

Willis: “Yeah, they, they actually tryin’ to go public. They tryin’ to take this, this part of the company public. And by doing, what they been instructed they need to do is to have contracts with major, large companies, large corporations and recycling their computers. They looked around and said, well, hell, let’s go after state. Nobody’s goin’ after state contracts.”

Dixon: “Uh huh.”

Willis: “Let’s go after that. We get two states, we definitely can take this thing public, you know? And so that’s their goal. Their goal is to take that company public inside of five years.”

Dixon: “Uh huh.”

Willis: “Do whatever they have to do to take it public. They don’t, they don’t, whatever, ’cause once they take it public they all multi-millionaires.”

Perjury 201:

Students will learn the difference between perjury, making false statements (or what the feds call “Section 1001’s”), and having sudden memory loss in front of a grand jury. Former Memphis City School Board member Michael Hooks Jr. was charged last week with making a false statement. But Roscoe Dixon wasn’t, even after this session with the FBI two weeks before he was indicted in May 2005. TSFS graduates know when to say no — and that’s no lie!

FBI: “So I just wondered if in 2004 you never took money from Tim Willis.”

Dixon: “No.”

FBI: “Okay, no you didn’t. And he never gave you money in an office, in that office.”

Dixon: “No. No.”

FBI: “Okay.”

Dixon: “Not to my knowledge. Not to me anyway, to my knowledge. Let me, let me just research my memory. He took us to dinner.”