Actors Emily Blunt and John Krasinski are both expert at little looks. Their microexpressions often betray a tome’s worth of worry, regret or disdain, Krasinski’s most famously into the camera in the American version of The Office.

Their marriage has produced, besides two children, A Quiet Place, directed by Krasinski and starring the couple. It is a horror film which concerns a family in the country terrorized (as is their entire post-apocalyptic world) by blind monsters who echo-locate and horribly maul anyone who makes a loud noise.

This leads to the family and film being artfully silent. There is little dialogue, and most of it is in American Sign Language. The sound design is highly detailed, emphasizing every tiny movement and scrape as the family goes about its farm life sometimes on literal tiptoes.

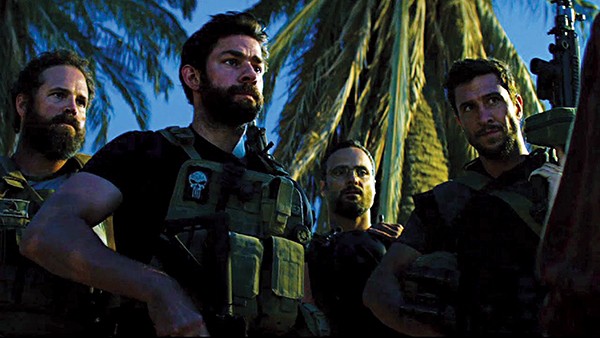

John Krasinski

Creaky boards are navigated with care, everyday objects put down like ticking bombs. Every task on the the Abbott family farm is an endless font of worry for both the family and the viewer, who is kept successfully in suspense throughout every simple chore. It’s a literalization of the way in which movies use quiet to soften viewers up before a jump scare, of which there are plenty here.

As in other ambitious modern horror films, like The Babadook and It Follows, fighting the monsters also doubles as a need to heal, in this case guilt and anger over the loss of a previous family member who made a sound. The Abbotts’ daughter Regan (Millicent Simmonds) feels she is left out, not only because of her negligence in the previous death and her youth, but because she is deaf.

The film’s carefully constructed ambient sound drops out for her scenes, muting them. It’s a nice touch, and one that highlights not only her perspective but mirrors the estrangement nonfictional deaf people feel when they are similarly mistreated, in non-post-apocalyptic situations.

The healing, when it comes, is a little too neat, and eventually the movie is less about metaphorical fears of letting go and more about the logistics of running and hiding from giant monsters. The monsters themselves look like a slightly more tasteful version of Resident Evil Lickers (the film also shares a composer and a final image with the 2002 film), and suffer a little for being familiarly CGI mutants. But they are scary, by simple dint of appearing from nowhere and killing any noisemaker, and work as a serious threat. No explanation is given for their presence, and none needed, as it would just get in the way. An old newspaper hints at humanity’s finding out how they work: “It’s Sound!” screams The New York Post.

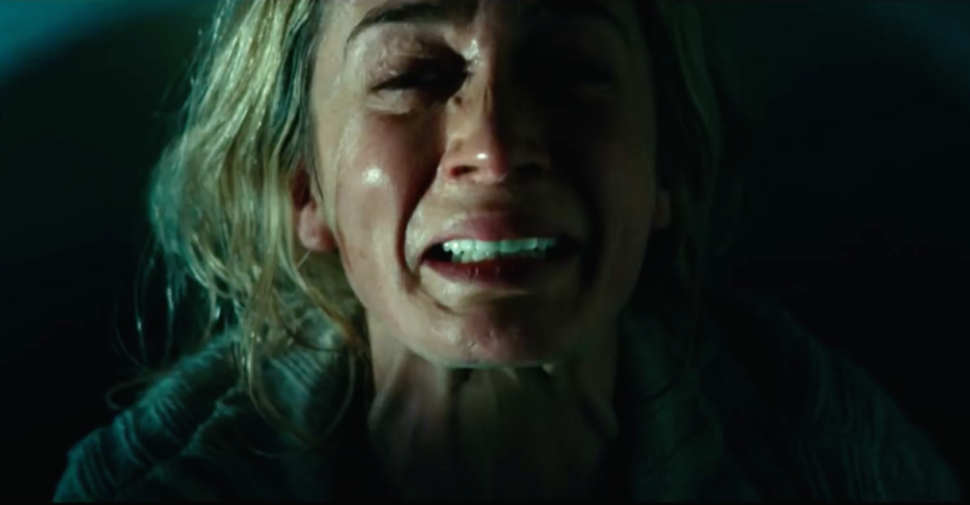

Krasinski does good directorial work, and gives Blunt, whose character is pregnant, many opportunities to panic, cry, and stoically work up the resolve to deal with nearby monsters, sounds and children. The family again and again must take great pains to repress themselves, and the work of self-repression builds and builds, until it becomes an unnavigable burden. Their movements cry out.

Emily Blunt

Blunt’s great, almost as excellent at registering horror and shock with thoughtful composure as she was in the scarier cartel drama Sicario. Krasinski’s bearded dad wears a look of exasperation, continually pulled in different directions by the exigencies of monster prevention and the emotional needs of family members. (As with many onscreen dads, proper care of the family unit is a spiritual calling and almost an impossible task: if we did not know he was also the director, his cross would seem just a bit too burdensome.) When the two finally have spoken, whispered dialogue, it feels unusual and focuses entirely on their unresolved emotions.

Horror films are really tragedies. When they’re not concerned with gore or sex they’re about tension, the fear and buildup to the horrible outcome, be it murder or worse. They’re an openly acceptable way for a light entertainment to discuss feelings of despair and helplessness.

They focus on the inevitable lead up to ruin, and the faces of people who see it coming, paralyzed in its sway. Their doom is often unavoidable, their hard work rewarded with bright fake blood and the loss of worry forever. But the discussion of their fate, although it’s fictional and with less critical or popular respect than other art, is enormously cathartic to anyone who feels that doom, in any way, in their day-to-day.