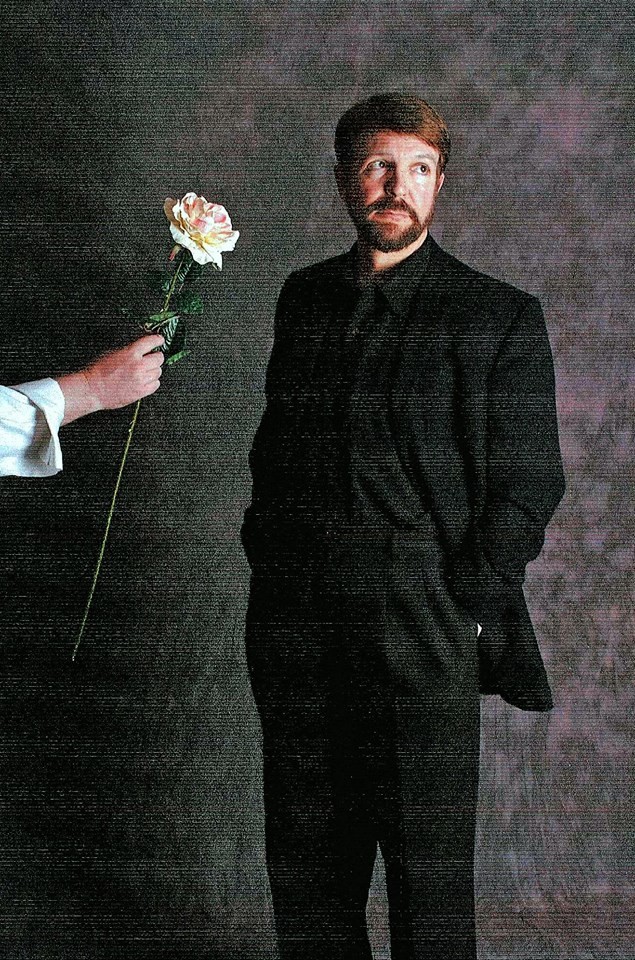

John Rone. Promotional image from GCT.

John Rone sent me messages sometimes. Maybe just a “happy birthday,” greeting. Or maybe he’d tell me about a play he’d seen at some festival. Now and then he’d sign these notes, “Love, Dad,” or some variation on the theme. Now that he’s gone, I’d like to set the record straight: This man was not my father! Sure, fathers are awesome and all, but in the strictest sense, everybody’s got one. Next to mothers and mystery novels they’re the most common things in the world. And, while John Rone certainly loved a good mystery, there wasn’t much else common about him, or the friendships he forged across the span of a life well- lived.

No doubt John will be remembered for his elegance, erudition, and wit. I especially appreciated the way he met and worked with people on their own terms. This was true whether he was working the day job at Rhodes College or putting on his director’s cap to coax his ensemble through a difficult scene. Or maybe he was just responding to a smart-assed alum who’d promised/threatened to liven up an artist’s wine and cheese reception with whoopee cushions.

Too much? Maybe a little. But I’m so damn tired of writing obituaries — stuck in the anger stage of grieving, if you will — and something tells me Mr. John Howard Rone would rather we laugh or snort or blush and avert our eyes or feel anything at all other than sadness or madness that he’s left us so soon. Like I said up top, there’s no one else I can think of quite like this eager, loyal, loving, dapper and slightly devilish man of Memphis. My heart could drop an epic. The fingers may only manage to type a few, insufficient paragraphs.

The longer I sit, looking back over 34 years of acquaintance, trying to boil a rich, multi-faceted life down to pure essence, the more my mind is drawn to a moment in 2017 when John and I met in the Paul Barrett Jr. Library on the Rhodes campus for a wide-ranging talk about the history of Germantown Community Theatre wherein he compared the rapid succession of executive directors to ancient Rome. “There are all these Caesars that come in, and some of them don’t stay very long,” he said rattling off a list of names that went on and on like the closing scene in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. That’s when he told me he was delighted to be able to identify himself as “a full-time theater director” now that he’d retired from his Rhodes position as director of the Meeman Center for Continuing Education. He was working for GCT at the time, staging Arsenic and Old Lace and looking forward to bigger and more demanding projects. I’m stuck on this image and the false promise of a best that wasn’t yet to come.

As an actor John could flit from classic to contemporary at the bat of an eye. Larry Shue’s perpetually relevant comedy The Foreigner was a signature show, but John moved fluidly from Shakespeare’s tragedies to Tom Stoppard’s oddities, and seemed most at home in the role of director. Tennessee Williams and I Am a Camera author John Van Druten were favored playwrights, but behind the scenes he showed a special flair for teasing out dense plots and finding the life in stories more literary than dramatic.

The Memphis Theater Community Says Goodbye to John Rone

I know I just referenced Cymbeline like it was a well known show that everybody’s familiar with, but I’m going to guess most readers haven’t seen or even studied Shakespeare’s Disney-ready tale of Imogen, a royal badass who sticks it to the patriarchy and marries for love. It isn’t done very often, in part, because the infamous last scene stretches out toward infinity in an unlikely cascade of confession and coincidence that ties every loose thread into a comic, practically post-modern tapestry of too much resolution. In an early 1990’s production for the McCoy Theatre at Rhodes, John treated that scene like the shaggy dog gag it is. His cast, a healthy mix of student and community actors, made the dreaded denouement sing. It’s still one of the best stuck endings I’ve had the pleasure to witness, and an exemplary sample of John doing what he did best.

The Memphis Theater Community Says Goodbye to John Rone (2)

A few more paragraphs might be generated listing honors and achievements. Instead I’ll link to other sources and only note that John and his equally remarkable and universally beloved partner Bill Short are both Eugart Yerian Lifetime Achievement Award honorees, marking decades of fierce, fully committed devotion to Memphis’s theater community. That represents a lot of collective service.

To bring all of this full circle, John did play my father once, in a lewd and lovely romp through Oliver Goldsmith’s naughty 18th-Century comedy, She Stoops to Conquer. In that role he took wicked delight in spanking my Marlowe’s badly-behaved bottom with whatever object he happened to be holding in his hand. Sometimes he used a cane, but it might be a riding crop, hair brush, or what have you. He was quite skillful with the “what have you,” I seem to recall, and from that time forward, the sinister (but loving) threat of a surprise cuff, cudgel or swat lurked whenever “dad” was near. I don’t think I’m going to miss that, honestly. But I’ll miss damn near everything else.

A private service for family has been scheduled at Grace-St. Luke’s Episcopal Church,Thursday, February 14th. Although the date hasn’t been set, a more public celebration of Johns’ life will be held at Theatre Memphis sometime in the near future.

Donations in John’s memory can made to Rhodes College, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, or — of course — a favorite theater company.

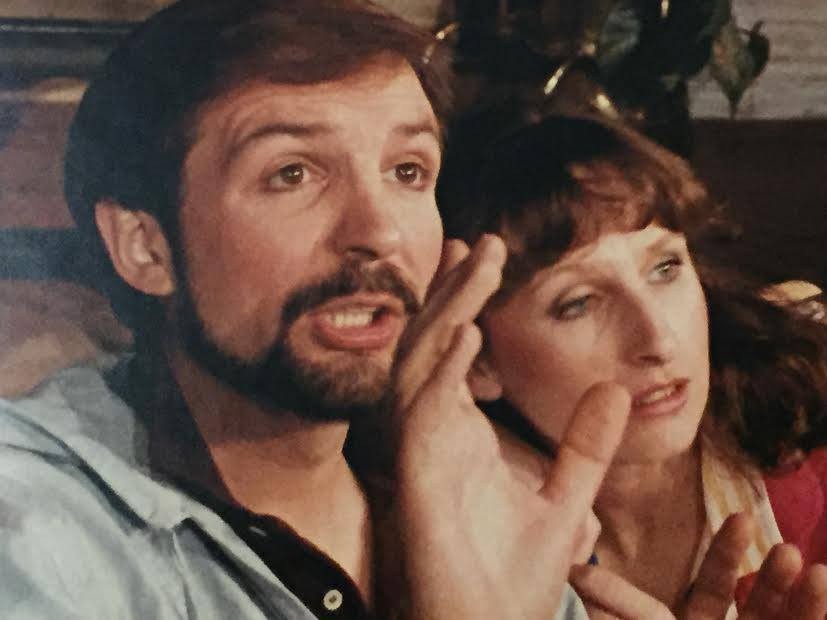

John Rone, Claire Orman in ‘Lunch Hour.’

Theatre Memphis

Theatre Memphis