Editor’s note: Citywide planning, land use discussions, zoning, and the potential economics of it all are far too broad and dense to ever be covered in a single news story. (So are other considerations about income, race, and population loss.) Please consider this piece the beginning of our coverage on Memphis 3.0.

For this one, we’ll take you inside one of MidtownMemphis.org’s information meetings and share a Q&A rebuttal about it all from John Zeanah, director of the Memphis and Shelby County Division of Planning and Development (DPD).

Memphis 3.0 will “sell out” Midtown neighborhoods to investors and businesses looking to cash in on (but maybe never really care about) the attractive communities residents in those places have built over decades.

That’s a very basic expression of the argument voiced for months now from MidtownMemphis.org. The volunteer group is fighting the plan with a series of information meetings, an online information hub, and yard signs — sure signs that a Midtown fight has gotten real.

Passed in 2019 and devised by former Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland’s administration, Memphis 3.0 is a document guiding the growth of Memphis. It’s up for its first-ever five-year renewal. A major strategy for sustainability in the plan has been to support some of the city’s anchors like Crosstown Concourse, Overton Square, and commercial areas around Cooper Street.

However, MidtownMemphis.org argues the locations for these anchors and the planned density that could surround them aren’t fair. For example, group members say a lot of density is planned for Midtown but very little for East Memphis.

Also, adding density to certain places around Midtown means multifamily homes, the group says, instead of single-family, owner-occupied homes. They fear profit-minded landlords will use 3.0 to work around zoning laws to create duplexes or quadplexes, won’t upkeep these properties, create transient tenants, and make neighborhoods less attractive for potential buyers. They say this could slowly destabilize neighborhoods into ghosts of their current selves.

“What we’re against — and we have history on our side — is destabilizing the neighborhood to support Crosstown,” said MidtownMemphis.org volunteer Robert Gordon, who has spearheaded the battle against 3.0. “[The plan] is going to wreck Crosstown, wreck the neighborhood, and, consequently, wreck the city. And if you don’t believe me, go back to Midtown in 1969. Go back to Midtown in 1974. Go back to Midtown when it was zoned like the [Memphis 3.0] future land use planning map envisions zoning.”

All of it, they say, could lead to a showdown at Memphis City Hall next year as council members review the changes for a vote.

However, John Zeanah, director of the Memphis and Shelby County Division of Planning and Development, said the 3.0 plan won’t do what MidtownMemphis.org fears it will do.

“The goal is to make sure that our community has healthy, stable anchors that are supported by healthy, stable neighborhoods,” Zeanah said. “The suggestions that we would take extreme actions to destabilize neighborhoods is really puzzling. It doesn’t come from anything that we’re saying as a part of our meetings. It doesn’t come from anything the plan is saying.”

Inside a MidtownMemphis.org 3.0 meeting

A dreary, cold, wet February night was not enough to stop a crowd from sloshing through puddles to hear about how the Memphis 3.0 plan could “sell out our neighborhood,” as the signs say. Nearly 60 people gathered for a MidtownMemphis.org 3.0 meeting earlier this month at Friends For All.

MidtownMemphis.org has been holding meetings like these since September. Other info sessions — six in total — have been organized at Otherlands Coffee Bar, the Cooper-Young Community Association building, and the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library. Gordon said it was in January that planing officials stopped working with MidtownMemphis.org on the 3.0 issue.

At the latest February meeting, Gordon took the stage before a slideshow projected on a screen behind him. He described MidtownMemphis.org as a “sort of neighborhood association for neighborhood associations,” meaning his group meets monthly with Midtown neighborhood groups from Central Gardens, Cooper-Young, and more. MidtownMemphis.org also plants trees around Midtown and oversees the community garden next to Huey’s Midtown.

Gordon told the crowd he entered public planning discussions as a NIMBY (not in my backyard), concerned that the Poplar Art Lofts plan in 2019 would push noise and exhaust onto those enjoying Overton Park. This led him to the MidtownMemphis.org organization and he’s been a volunteer with the group ever since.

Gordon described the 3.0 plan as a “city guide” and a “North Star” for Memphis-area planning efforts. The plan’s motto, he said, reverses the sprawl strategies of years past and embraces the idea to “build up, not out.” While the motto is the essence of the plan, Gordon called it “quite misleading.”

One critical foundation of the Memphis 3.0 plan is where that growth inside the city’s footprint should happen. The plan says that growth should happen around anchors. These anchors, picked with the help of residents, are usually commercial areas like Overton Square, Crosstown Concourse, Cooper-Young, and others.

To Gordon, city planners dropped a compass point on these anchors and drew a circle around them. Inside those circles is where the 3.0 plan wants to grow, he said. This is a critical foundation of MidtownMemphis.org’s argument against the 3.0 plan, with Gordon saying, “I’m not alone in thinking that’s a bad way to make plans.”

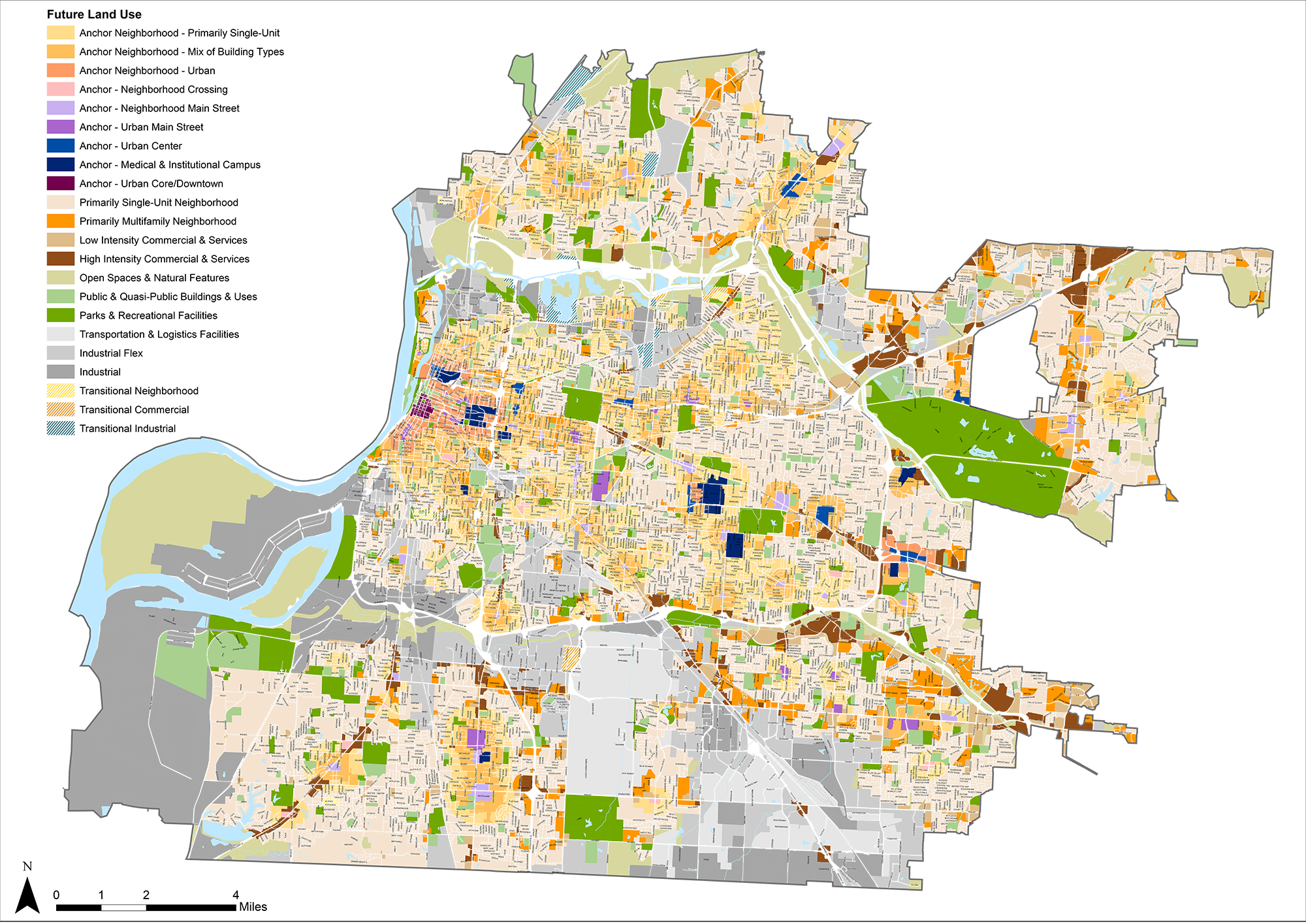

“So, you may have bought your home in a single-family neighborhood, but the future land use planning map sees in the future … a change to a more dense kind of neighborhood,” Gordon told the crowd. “One of our big issues with [3.0] is right here at the core of it: the anchors. We don’t agree that an anchor necessarily warrants this kind of density. Nor do we agree with what are called ‘anchors.’ For example, let’s just point out, Overton Park is not an anchor.”

The anchor model and the density projections that come with it are brush strokes too broad to paint the intricacies of planning something as complex as Midtown neighborhoods, Gordon said. This is seen at a macro level in the plan as the city is divvied up into 14 planing zones. In this, Midtown, the Medical Center, and Downtown are merged into one zone called “Core City.”

“I think that is a mistake because Midtown is residential housing, and Downtown and the Medical Center are not,” Gordon says. “So, let’s start by saying those should be separated.”

But Gordon easily shifts into the micro: the dense, complex, nitty-gritty of 3.0 that could allow single-family neighborhoods to legally be chopped into quadplexes, new units built where they can’t be now and, he says, destabilize Midtown neighborhoods.

The density models from anchor planning in 3.0 are the easiest way for a developer to create multifamily in a single-family zone, he said. They’ll pay “professional convincers,” basically development lobbyists at Memphis City Hall, to speak to planning boards like the Land Use Control Board or the Board of Adjustment and ask for a special zoning change on property from single family to multifamily.

“This professional convincer is going to go in there armed with information from Memphis 3.0 and say, ‘This is what the city wants,’” he said. “So, in short order, your single-family neighborhood is going to begin to show multifamily buildings. And people who are looking for houses to buy are going to go, ‘Wait a minute. I remember this as a single-family neighborhood. What’s that four-plex doing there?’”

While the process may move slowly, he said, it could be a deciding factor for potential Midtown homeowners who might not want to gamble their biggest investment “on a neighborhood that’s in flux.”

A neighborhood could get multifamily zoning even if it’s not in one of those anchor density zones, Gordon said. The Memphis 3.0 plan designates some entire streets for higher density, regardless of where they lie, he said. So, even if your neighborhood passes all the other tests, a developer could use the street designation as an argument for, say, a four-plex on a street. Later, another developer could come in wanting the same thing nearby because there’s already one across the street.

A third way Gordon told crowd members a neighborhood could get density through 3.0 is from degree of change. He joked it was the “dreaded degree of change” because it was harder to explain. The term, he said, basically means how money gets into a neighborhood. The 3.0 plan outlines three categories, he said. In it, the city works alone or with developers to fuel projects in certain neighborhoods, based on the need, and that could mean high-density housing.

“If you’re in a ‘nurture’ neighborhood, the city’s going to throw a lot of money at you,” Gordon said. “If you’re in an ‘accelerate’ neighborhood, the city’s going to throw some money at you but they’re going to try and get private investment to come in.

“If you’re in a ‘sustain’ neighborhood, then the city’s is going to say that private investors are going to take care of that.”

A contentious question of motivation

The Q&A portion of the meeting found a raw spot in discussions around Memphis 3.0 and the density topic in general. The basic question: Are single-family housing proponents seeking to bar low-income people from their neighborhoods?

Abby Sheridan raised the point gently at the MidtownMemphis.org meeting. The reason she and her family moved close to Crosstown, she said, was to be within walking distance of the Concourse, for the density. She went to the meeting to see what the opposition to 3.0 was about, she said.

“Don’t be afraid of density,” she told the crowd. “Just because we allow for different types of housing doesn’t mean it’s an automatic guarantee.

“I’ve lived in multi-unit neighborhoods for most of my adult life. They are thriving, vibrant communities.

“If we, as Evergreen [residents], believe that diversity is our strength, y’all are really showing your colors tonight.”

The comment sucked the air from the room that was quickly filled with side chatter, sighs, and low gasps. Emily Bishop, a MidtownMemphis.org volunteer, responded, saying owner-occupied homes stabilized Cooper-Young in the late ’80s when she bought her home (once a duplex, she said) there.

“The businesses were nonexistent in Cooper-Young,” Bishop said. “There was one Indochina restaurant. [The neighborhood] was light industrial at best.

“There was no zoning change that brought density back. What makes a neighborhood thrive are owner-occupied homes with people who get involved, who do the code enforcement work, who get rid of slumlords, and who support the local businesses.”

In all, Bishop said Memphis doesn’t have a housing shortage; it has an affordable housing shortage.

“And there again,” Sheridan said, “what I’m hearing you say is … ‘not in our neighborhood.’”

Gordon jumped in to cool off the topic by saying that MidtownMemphis.org really is simply in favor of doing smaller plans for distinct neighborhoods.

Joe Ozment spoke plainly.

“I’ve been doing criminal defense in this city for 33 years and I’ve seen what’s happened in areas like Hickory Hill and Cordova when you add density,” he said. “We don’t want that in Midtown.”

Jerred Price, president of the Downtown Neighborhood Association, and his board attended the meeting to “support the neighbors.” He and the board agreed that Downtown should be a separate planning bloc from Midtown. He said the anchor-and-compass method “shouldn’t be a strategy for development.”

Dropping “one of those special, little circle-drawing thingamajiggers” at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital would mean high density for the single-family neighborhoods like Uptown, he said. But higher density could be welcomed on the other side of the interstate there because it’s in the Downtown core.

“So, even for us, those circles don’t make any sense of our communities,” Price said. “We stand with you on that.”

Asked about the timeline of the Memphis 3.0 proposal, Gordon said public meetings will continue through this year. Revised plans with that public input would then be published. Then, the Memphis City Council would vote on them, likely in 2026.

“If the future land use planning map hasn’t changed,” he said, “we will continue to marshal forces and the idea will be a showdown at city council.

“We would bring many citizens up there to protest a map that is not properly planned and does not look at what is stable in Midtown, is determined to destabilize Midtown for the benefit of commercial anchors, and is giving a free pass to other parts of town.”

Q&A with John Zeanah

John Zeanah is the director of the Memphis and Shelby County Division of Planning and Development. He said overarching city plans like Memphis 3.0 are nothing new; they’re even mandated for cities in certain states.

Among those plans, Memphis 3.0 stands out, Zeanah said. It has won awards from the American Planning Association and the Congress for the New Urbanism. Memphis 3.0 is the city’s first comprehensive plan since 1981.

We asked him to respond to the movement against the 3.0 plan, which was authored by his office. — Toby Sells

Memphis Flyer: What do you make of the arguments about 3.0 from MidtownMemphis.org?

John Zeanah: Memphis 3.0 was adopted six years ago. So, when is it going to do those things [that MidtownMemphis.org argues] if it hasn’t already?

They’re saying the plan is up for a five-year review.

We’re undergoing our first five-year plan update now. One of the things that we’re doing as a part of the five-year plan update … is conducting a comprehensive look at the zoning map and understanding how well our zoning works with [Memphis 3.0].

I think part of the misunderstanding is the claim that we would necessarily rezone areas, according to the plan, to the most intense use or the most intense zoning district that could be conceived. And that’s not the case.

First of all, [Memphis 3.0] is general in nature. It — and the future land use map that they are so worried about — is meant to be general, with a generalized land use map.

I think there’s some misunderstanding about whether the future land use map is calling for all these new things to happen. It’s an expression of what’s existing today. In some cases, it’s a mix of both.

Suffice to say, as we are going through the five-year plan update and we’re thinking about how zoning is a tool to implement the plan, our orientation is not to just apply the most-intense zoning district. There are changes to zoning that may not always be in residential areas. In fact, I’d say most of the zoning changes that will end up being recommended are in some of our commercial areas and commercial corridors.

The goal is to make sure that our community has healthy, stable anchors that are supported by healthy, stable neighborhoods. The suggestions that we would take extreme actions to destabilize neighborhoods are really puzzling. It doesn’t come from anything that we’re saying as a part of our meetings. It doesn’t come from anything the plan is saying.

They’ve said developers could use the future land use planning map as another arrow in their quiver. They could argue that while multi-family homes may not be allowed in a zone now, they could point to the suggestion in Memphis 3.0 and make a case for their project at city hall.

One cannot simply point to a generalized land use map and say, “Well, because this area around an anchor is a mixed-use type, I should be entitled to do the most intense thing that is part of this mix.” That’s no. 1. And no. 2: The plan does not have the authority to entitle that. That’s the role of zoning.

So, if you live in a neighborhood that is predominantly single-family and your zoning is single-family detached, and it is a stable neighborhood, there is no reason for the city to propose changing the zoning for the neighborhood. You are the healthy, stable neighborhood that is helping to support the anchor nearby. That is a good thing. That’s what we want to help preserve.