Sun Studio is the body around which Memphis music orbits — and where it all began. Jim Stewart at Stax saw Sam Phillips selling records and bought his own recorder. Two of the founders of Hi Records came from Sun. Phillips showed everybody the way. The radio engineer from north Alabama set Memphis music in motion from 706 Union Avenue.

“There are a lot of people who think the music is magic, and it does have a magic quality to it,” says Jerry Phillips, Sam’s youngest son. “But my dad always said it’s who you’ve got in there. Who knows how to operate the equipment and place the microphones? You’re not necessarily going to have a hit because you’re in that room. Or get that sound at all.”

The person operating Sun Studio today is Matt Ross-Spang, who was a Germantown High student when he set his sights on the room that Phillips opened as the Memphis Recording Service in January 1950. Ross-Spang is finishing a years-long effort to return the hallowed studio to its original condition, complete with period-correct equipment and all the discipline that old gear forces onto engineers and artists alike. It’s not the sort of task a typical person assumes, but Sun Studio was never a place for typical people.

“He’s a young man with an old soul. Matt’s got a lot of Sam Phillips in him,” Jerry Phillips says. “He loves that equipment and the simplicity of it all.”

Sam Phillips was famous for his ability to sense the emotional content of a recording and to anticipate how listeners would respond. Phillips’ intuition came from a childhood exposure to African-American sounds that he heard in the cotton fields of north Alabama. His love for music drew him into the radio business, where he learned to work a nascent technology through which he commanded the airwaves, electronic signals, and a generation of American teenagers to dance to those sounds. Phillips had a gift for musical intuition, but he was also an engineer.

“He took a course at Alabama Polytechnic Institute and an engineering course at Auburn. I don’t think he went to Auburn, but it was through the mail” Jerry Phillips says. “Of course, when he got to his recording studio days, he installed his own equipment, hooked it all up, built the speakers. I wouldn’t necessarily call him a gear-head, but he was a gear-head by necessity. He had to do the things he was capable of doing, because he didn’t have much money. As a general rule, he was very interested in equipment and technology.”

Phillips worked in audio when audio was new. He became a radio engineer in Muscle Shoals in the late 1940s. At that time, music was cut onto lacquer discs by a lathe. It was not until after World War II that Americans became aware of recording to magnetic tape, a technology developed by the Germans. “Tape recording” as we know it was originally funded in the U.S. by Bing Crosby, who saw that the possibility of recording sound to the quieter, longer-format medium would allow him to spend less time in the broadcast studio and more time on the golf course. Crosby spent $40,000 to bankroll the Ampex tape corporation in 1947. Phillips opened Memphis Recording Services two years later.

Matt Ross-Spang sits in the control room of Sun Studios, surrounded by machines that seem to have come from a 1950s sci-fi movie. On the other side of the glass, a large tour group sings along to Elvis’ “That’s All Right.” The tourists peer through the window at Ross-Spang as he talks about his job.

“Sometimes its like being in a zoo. You’re in the cage,” Ross-Spang says. His “office” is historic, a fascinating place. But it’s also a working recording studio as well as something of an ad hoc mental health facility. Like Sam, Ross-Spang has to understand both human and electronic circuitry.

“When people come to [record at Sun], they are freaked out. You have to let them Instagram and calm down. If you’re not a sociable, welcoming guy, they’ll be puking or freaking out. You won’t get anywhere.”

Ross-Spang asked for these problems. He’s had Sun on his sonar since he was a kid.

“I recorded here when I was 14,” Ross-Spang says. “I did this god-awful recording, I mean god awful. It was so bad. I played acoustic and this guy played a djembe drum with eggs. That’s how bad it was. But I met James Lott, who had been the engineer for 20 years at the time. So, to me, it was like the coolest thing in the world being in Sun. A lot of people get captured by sound. I wasn’t captured by sound at that point, but when I watched him manipulate the sound, I was like ‘You can do all of that?’

“Trying to save what I did out in the studio, I just bugged him a bunch, and he told me to come back and intern with him,” Ross-Spang says. “I came back when I could drive. So I came to work here when I was 16. The other intern didn’t last that long. I started interning for him when I was about 17 or so. After high school, I would come down and do tours as a tour guide. And then I’d intern until about two or three in the morning. I did that for about six or seven years and then took over as head engineer about five years ago. I’m one of the few people who figured out what they wanted to do really early on. And it was Sun Studio.”

Long before Ross-Spang arrived, the facility had been abandoned by the Phillips (who never owned the building) in 1959. It sat empty, then housed other businesses. According to Jerry Phillips, a combined effort by Graceland, the Smithsonian, and Sam himself saved the place from the typical Memphis fate of abandonment, demolition, and dollar store. The studio was rebuilt according to Sam’s memory before being purchased by Gary Hardy in the late 1980s. The current owner is John Schorr. But Ross-Spang is the driving force behind rebuilding the room to Sam’s specs.

“It’s fantastic that [Ross-Spang] has pursued this with such scholarly devotion,” says Peter Guralnick, author of the definitive, two-part Presley biography, Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love, who is currently at work on a biography of Sam Phillips. “Sam was systematic in thinking about sound and gave great thought to it — no square angles; the tiles. In addition, he felt there was something unique about the room at 706 Union. He didn’t know it when he rented it. To have reconstituted it is an exercise in creative archeology.”

Ross-Spang is certainly diligent, but there were some lucky (and unlucky) breaks along the way.

“I became the head engineer at Sun Studio when I was 22. I didn’t have any money. I had one guitar. It was a beautiful, big Guild. It was signed by Robert Plant, Elvis Costello — people I’ve met over the years and hung out with here. One night, while I was away, it got smashed, and I got an insurance check from the studio for it. It was a huge chunk of money for me. The whole time I’ve been at Sun, I’ve wanted to put the original stuff in. Sam used this old 1930s RCA tube console. But you could never find those things. People just threw them out in the 1960s. But one popped up on eBay, two days after my guitar was smashed. The only way I could have bought it was with the insurance check. To this day, I think my X-Men ability is that if I need something and I think about it hard enough, it pops up on eBay. I bought that, and the studio bought other stuff. It’s taken about five years, but now it’s all here.”

Ross-Spang bought a 1936 RCA radio mixing console, the same model Phillips paid $500 for when he opened Memphis Recording in January 1950. Phillips originally cut records onto discs with a lathe and switched to analog tape in late 1951.

“I’ve got the same 1940s Presto lathe that I can cut 45s on. All the Ampex, all the microphones are period-correct to what he used in the day. It’s becoming exactly like it was in 1956.”

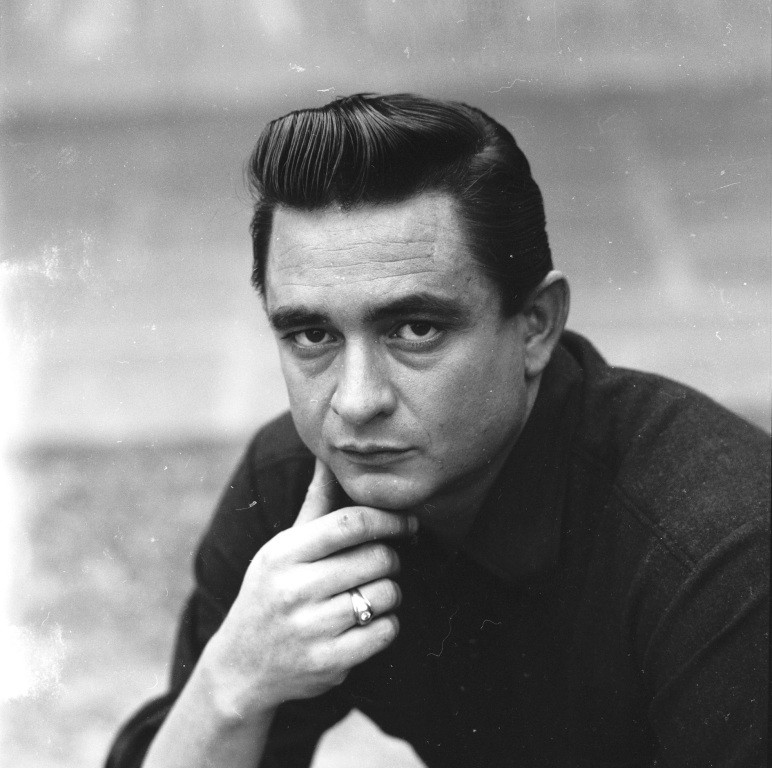

In 1956 at Sun, Johnny Cash recorded “I Walk the Line.” Orbison cut “Ooby Dooby.” Billy Lee Riley recorded “Flyin’ Saucers Rock & Roll.”

“Mark Neil, who did the Black Keys’ Brothers album, is a huge Sun fanatic,” Ross-Spang says. “He helped me locate stuff and figure out how Sam did it. Back then, there was no ‘normal’ way to do things. A lot of the stuff was homemade. We really had to use our ears and listen to records. There were only five pictures in the studio back then. It’s not like the Beatles, where we know exactly on June 2, 1966, George Harrison sneezed. We don’t have any of that kind of info. A lot of the old guys don’t really remember. Scotty Moore was an engineer after Sun, so he remembered a lot more than anybody else. But even then, Scotty might say one thing, somebody else might say another.”

Moore, who played guitar on all of the better Elvis records before the late 1960s, proved to be more than a historical resource for Ross-Spang.

“I’m lucky enough to have known the Sun guys for a long time,” Ross-Spang says. “I’d go visit [Moore] every couple of months in Nashville. Once, Chip Young was there and they both busted out guitars. Chip brought out his Gibson Super 400. Chip Young is one of my favorite guitar players of all time. He played with Elvis and some other people. So they are all playing at Scotty’s, and then they passed it to me.”

For Ross-Spang, who plays guitar in the Bluff City Backsliders, it was terrifying: “I’m thinking ‘What am I going to play in front of y’all?'”

The job and the friendship with Moore later put Ross-Spang in an awkward place.

“A year or two ago, I did a record with Chris Isaak here. And, this January, the BBC wanted to do an interview with Scotty, but about his life, not about Elvis. They called me up and we kind of got some things together. We got Chris Isaak to host it. Then about a week before the producer called and said, ‘Hey, we thought it would be great if they cut the Elvis songs again.’ That’s great, but Scotty hasn’t played guitar in like five years; he just doesn’t do it anymore. They said, ‘That’s fine, you do it.’ I was like, ‘Great, you’re going to make me play my hero’s guitar licks in front of him in the place where he did it.’ Of course, I know all his licks. I’ve stolen them a thousand times. He’s saved my butt on sessions. But I’ve never had to do it front of everybody. And to make matters worse, I had invited Jerry Phillips, J.M. Van Eaton, everybody.”

But things got even weirder.

“A side funny thing was that Chris wanted to do the songs in E,” Ross-Spang says. “If you’re a guitar player, you know they’re in A. You can play them in E, but they don’t sound the same. I’m setting up the mics and I hear ‘Let’s try this in E.’ I’m going, ‘crap.’ I told Chris, ‘You know these songs are in A,’ and he says, ‘E is better for me.’ I’m wondering how I’m going to save my butt. I’m just thinking about me at this point. I know one person in this room who can get him to go with A.

“I said, ‘Scotty, Chris is talking about doing ‘That’s All Right’ in E.’ He was like, ‘What? Why?’ I said, ‘You should go talk to him.’

“We did them in A, and it sounded great. It came out really well. But I had bought a tube tape echo because of the one Scotty had at his house. Afterward, he said, ‘You know I’ve got one of those.’ I said ‘I bought one because of you.’ He said, ‘Well, hell, I’ll just give you my old one.’ About a month or two later he called me up and asked ‘When are you going to come get this thing?’ I wasn’t about to bug him about it. So I went up there as fast as I could. He gave me whole live rig setup from the ’90s. It had his tube echo. He used [effects] to try to simulate the quirks of tape. They all have his hand-written notes on them. It was one of the greatest days of my life. It’s like Yoda giving you his light saber.”

Working with the limitations of the last century might seem like a pain, but Ross-Spang, who was recently named governor of the producers’ and engineer’s wing of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences’ Memphis chapter, appreciates the discipline it takes to record an entire group’s performance without stopping — an art many consider lost.

“When you look at old pictures of Willie Mitchell and Sam, they’re kind of crazy looking,” Ross-Spang says. “They’re smoking, and they’re hunkered over a big piece of metal and knobs. Nowadays, if I get tagged in photos, it’s me hunkered over a mouse. Why would you take a picture of that? The magic is gone when you go all digital.”

Recording a whole room to mono means everybody has to get their parts right. You can’t fix a mistake. Perhaps the reason Al Green, Johnny Cash, and the Killer keep selling records 60 years later is that they made great music together at the same time.

“I love that way of making records. Everyone has to pay attention to each other instead of themselves. It’s a team effort, including me,” Ross-Spang says. “It’s not very forgiving. But I think one of the reasons people come here to do that is because it makes them a better musician. With the computer, you can play five solos, go home for the day, and the engineer will make a solo for you. But here, if you don’t get a solo right, you may have just wasted a great vocal take. There’s so much more on the line. But that makes you play better too. It’s the only way I like to work now. People hire me to work in other studios, and I try to take the same mentality. It doesn’t always work, because they’ve got booths and headphones. You say, ‘Can you turn your amp down.’ They say, ‘Can I just put my amp in the booth?'”

He shakes his head.

“If you give a mouse a cookie, it wants a glass of milk.”