According to a recent issue of the New York Times Magazine, filmmaker Oliver Stone had said, after making a career of focusing on political message vehicles — think JFK, Nixon, Born on the 4th of July…heck, even Platoon and Wall Street, and perhaps most notably (or notoriously) the muckraking TV series-cum-book entitled The Unknown History of the United States —he had become loath to do anything more in that genre.

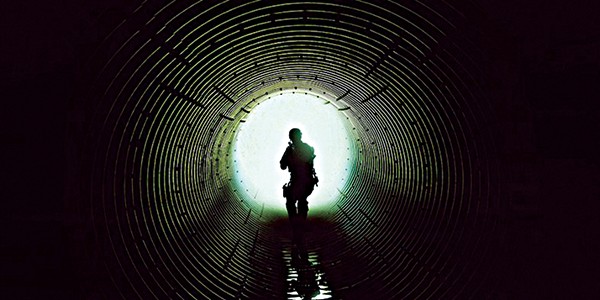

Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Edward Snowden in Oliver Stone’s Snowden

Well, then, surprise! Stone’s most recent venture, opening Friday night at the Paradiso, is entitled simply Snowden — after its subject, exiled programmer/cryptographer Edward Snowden, arguably the most famous whistle-blower of all time and certainly the one whose actions have had the most contemporary political impact.

This is the man — passportless as a result of his own government’s retribution and now holed up in Moscow, courtesy of that country’s America-baiting leader, Vladimir Putin — who released to the world a cyber-cornucopia of secret codes and programs demonstrating conclusively that America’s National Security Administration (NSA) had systematically abused this country’s laws and traditions by spying relentlessly on its citizens and those of various other nations, friendly and unfriendly.

It is easy to confuse the Snowden saga with that of such other whistle-blowers as Chelsea (ne Edward) Manning, the transgender soldier who made over to Wikileaks almost a million sensitive documents relating to military secrets and who languishes now at Leavenworth Prison, or with Mr. Wikileaks himself, the Australian programmer/journalist Julian Assange, currently suspected of two-way collaboration with the Republican Party and the Russian government in the outing of sensitive, embarrassing information involving the Democratic National Committee.

Snowden first turned up on film in the award-winning 2014 documentary Citizenfour, which focused on how he turned over his incriminating information to journalist Glenn Greenwald and filmmaker Laura Poitras. In Stone’s hands and as ably portrayed by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, something both more substantial and more ordinary. Snowden comes off as a youthful striver and over-achieving computer nerd with a full set of idiosyncratic and rather endearing personal quirks. He had what appears to have been a legitimate and somewhat conventional romantic life. After months during which various incarnations of the movie had been screened before a series of private international audiences, the final version got its debut in Paradiso and 80 other theaters, nationwide, on Wednesday night. It opens its regular run on Friday.

The audience at the Paradiso and those other early-bird venues Wednesday night got something extra after the screening — nearly an hour’s worth of live conversation between Stone, Gordon-Leavitt, Shailene Woodley (who plays Snowden’s ever-loyal but independent-minded girl friend), and, Snowden himself, on a remote from Moscow.

Given director Stone’s well-established political pedigree, it was a bit surprising to hear him assert, when asked, that he had no particular “takeaway” in mind for his movie, that he was a dramatist first of all and had discovered in his basic source materials — a non-fiction novel by Russian author Anatoly Kucherena and his own interviews with Snowden and his circle — the ingredients of a love story.

As disingenuous as that sounds, it is borne out somewhat by the movie Stone made, in which Snowden figures as no mere hacker but as a prized code-writer and developer for both the CIA and the NSA who, to trust the script, had become an agency man for patriotic reasons after 9/11. He created some of the very programs that, to his consternation, he would discover are being used for indiscriminate snooping.

We are repelled, along with Snowden, as we see his idealism and patriotic purpose mocked by the cynical use of cyber-technology, including his own programs, on the part of the government agencies he works for in a series of exotic international venues — Hong Kong, Geneva, Hawaii, Tokyo among them. Stone makes the most of these locales — almost in the travelogue sense of a Bond or Jason Bourne saga — and he manages to endow his bespectacled Everyman protagonist with some of that cachet as well.

An early scene involves a Turkish banker whom Snowden, armed by the CIA with a false name and a fabricated identity, has been urged to cultivate in Hong Kong — not for purposes of national security, as it turns out, but to hook into the financial assets of the banker, who is basically blackmailed after illegal snooping discovers that his son, who is moved thereby to attempt suicide, is an illegal resident and liable for deportation.

More disillusionment comes when Snowden views first-hand the carnage and collateral damage resulting from drone strikes that may or may not be targeting actual malefactors. But the ultimate epiphany is Snowden’s realization that the NSA has arrogated to itself the right to obtain access via cyber-snooping to the emails, telephone records, and innermost privacies of every citizen everywhere.

All of these professional dilemmas, meanwhile, are made to parallel Snowden’s personal drama with girl friend Lindsay Mills, a model and dancer whose political liberalism and emancipated personal credo (her provocative pictorials are getting hits a-plenty online), are juiced, in Woodley’s portrayal, with a soupcon of Girl Next Door. For Gordon-Levirtt’s Snowden, she manages to suggest both the Normalcy principle and Gatsby’s green light, both of which beckon him away from the tawdriness (and secrecy) of his professional life.

Regardless of how much poetic license might have gone into the effort, Stone has succeeded, at minimum, in rescuing his protagonist from the political-science abstraction of Edward Snowden Whistleblower and presenting him as Real Dude Ed Snowden, the possessor of both an accessible and likeable personality and an eloquence worthy of the issue he has come to represent.

Gordon-Levitt certainly succeeds in that respect, but the real coup de grace was delivered by Snowden himself, who, during the live chat of Wednesday night’s post-screening simulcast, was asked his reaction to seeing himself portrayed on film, private life and all. With evident sincerity, coupled with a sheep-eating grin and bona fide spontaneous blush, Snowden allowed as how he was a little bit embarrassed at being outed as “the world’s worst boy friend.”

That bit of self-deprecating charm was followed, moments later, by his serious answer to the question of why it is that, in this age of terrorism and international tension, it is important to safeguard a sense of privacy. For someone to suggest that governmental scrutiny is no problem for “those have nothing to hide,” is equivalent, said Snowden, to saying that free speech is unimportant only if “you have nothing to say.”

Face it: Oliver Stone is both a filmmaker and propagandist, and his movie is undeniably ex parte, but it is indisputable as well that both Ed Snowden and the eponymous film bearing his name have something to say.

And, even as arguments rage as to whether Snowden, still in danger of prosecution for espionage, deserves a pardon or, conversely, a prison, it is also indisputable that his actions have forced Congress belatedly to act, placing reasonable limitations on the NSA’s previously unbounded ability to invade the personal sphere of ordinary American citizens.

Politics and the Movies 5: Snowden