When I walk into my grandparents’ home, my Nonnie, Peggy, is standing over the stove. Bacon and eggs crackle in the skillet, and as I lean down to kiss her on the cheek, the sound of my Pop’s singing carries throughout the kitchen.

“Pop’s in his room,” she says, pointing to a closed door at the back of the house.

With every step, his voice and the strumming of his acoustic guitar grow louder and louder. I stand outside of his door and sing along under my breath to a song I’ve heard all of my life:

Sing your heart out, country boy

Sing your heart out

Play your guitar

Once I enter Pop’s room, I’m in his world. He’s holding his Martin, sitting in a chair with a four track and a page full of scribbled lyrics on a table in front of him.

“Hey, Grandson,” Pop says, standing up to hug my neck. “I had an idea come to me in the middle of the night, so I woke up and wrote it down. I’m trying to make sense of it now.”

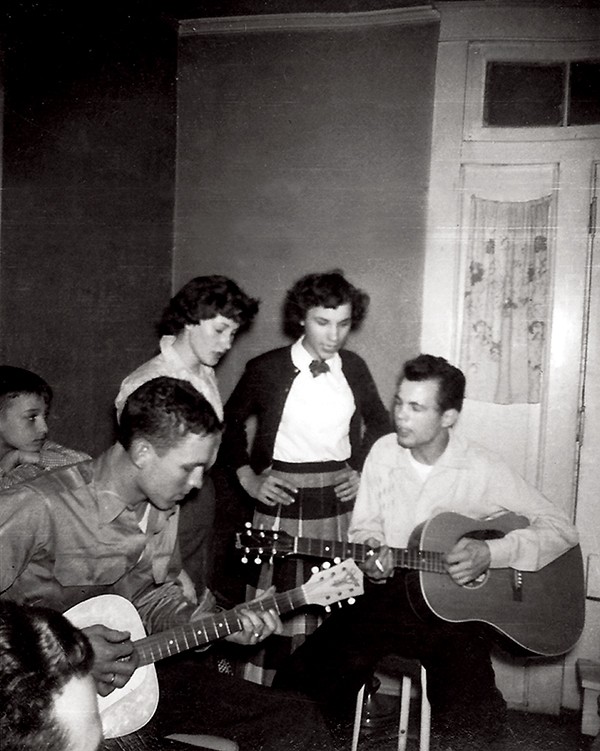

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

James Wesley Cannon plays a tune for his grandson, Joshua Cannon

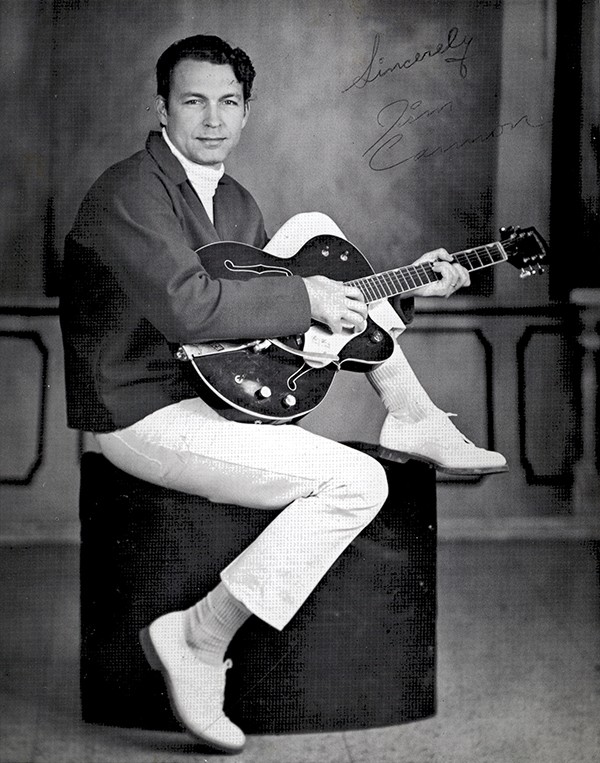

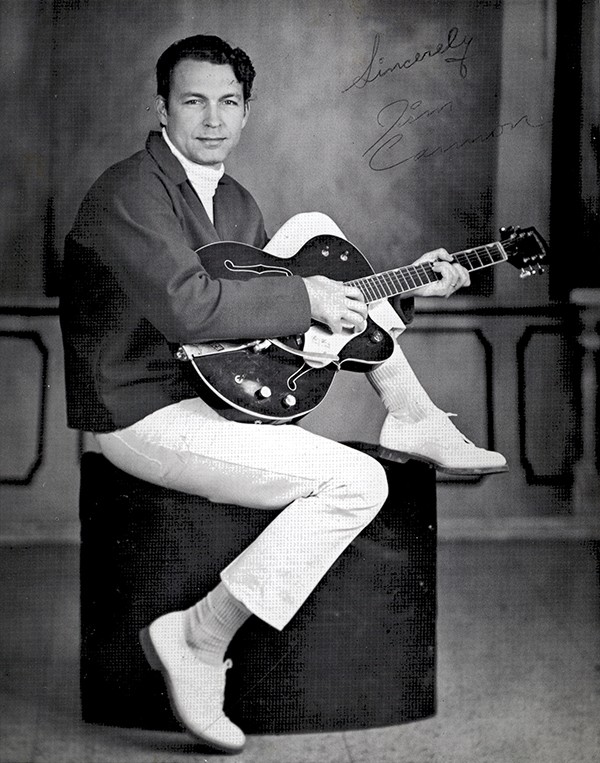

James Wesley Cannon has built his life around music. A teenager of the 1950s, he pioneered rockabilly alongside Elvis Presley, Bill Black, and many others. He’s still writing, hoping to put out another record of material he’s been sitting on for years.

At 82, his voice is still a booming baritone. When he digs deep into his belly for a stronger note, he finds a pulsating vibrato. His hair is as thick as ever, held together with pomade and hairspray. He’s rockabilly to his core.

Mementos of his musical pursuits decorate the room. Yellowed write-ups from Billboard, Rolling Stone, and the Memphis Press-Scimitar are preserved in Ziploc bags. A list of nominees from the fourth annual Memphis Music Awards, for which he was nominated for Outstanding Male Vocalist and Outstanding New Songwriter along with Alex Chilton, Al Green, Isaac Hayes, Willie Mitchell, Rufus Thomas, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley, are tucked away in a folder.

“James, Joshua,” Nonnie yells from the kitchen. Breakfast is served.

Nonnie’s cooking is no frills. Black coffee, greasy eggs. She’s been doing it all of her life for guests and family. Jerry Lawler, Larry Raspberry, Jimi Jamison, and Rufus Thomas — they ate her cooking. Pop and Nonnie always enjoyed entertaining people.

“I had a bad habit of walking up to people and saying ‘Hey, I want to talk to you,'” Nonnie says. “Next thing you know, we’d have them over for supper.”

We’re finishing breakfast when Pop’s phone rings. A smile spreads across face, the wrinkles in his cheeks revealing a man weathered by experience. It’s Johnny Black, one of the last-living friends from Pop’s childhood. Johnny’s older brother, Bill, was Elvis’ first bass player and later went on to have success with the Bill Black Combo. Bill recorded Pop’s first song, “Danny’s Dream Girl,” and pushed him to play music more seriously. In 1962, he opened Lyn Lou Studio on Chelsea Street, where he and Pop would spend hours working on mixes.

When Bill passed away in 1965 at just 39 years old, Pop was by his bedside, playing the songs they’d grown up on and written together.

“He was so full of music,” Pop says. “He would count with his hands like we did when we were in the studio together.”

Pop would later be the best man at the wedding of Bill’s son Louis Black.

“How do you feel about some company?” Pop asks Johnny over the phone.

He looks my way and nods his head up and down. We finish off the last of Nonnie’s coffee, and we’re soon on our way to have another cup with Johnny. He’s 83 and has just gotten out of the hospital after a close call with the flu. He and Pop have been making a point to see more of each other lately.

“Johnny told me he thought he’d be on a walker from now on,” Pop tells me. “I said, ‘Maybe you will and maybe you won’t. If you are, don’t give up on walking. Push yourself a little more every day. Don’t just roll over.'”

The two are notes from the same chord. Johnny saw Pop battle malaria and polio. They apply a similar mindset to music: against all odds, never stop.

When we arrive at Johnny’s house, the two men hug like long lost brothers. We sit down on the couch in his living room, and they are back at the beginning.

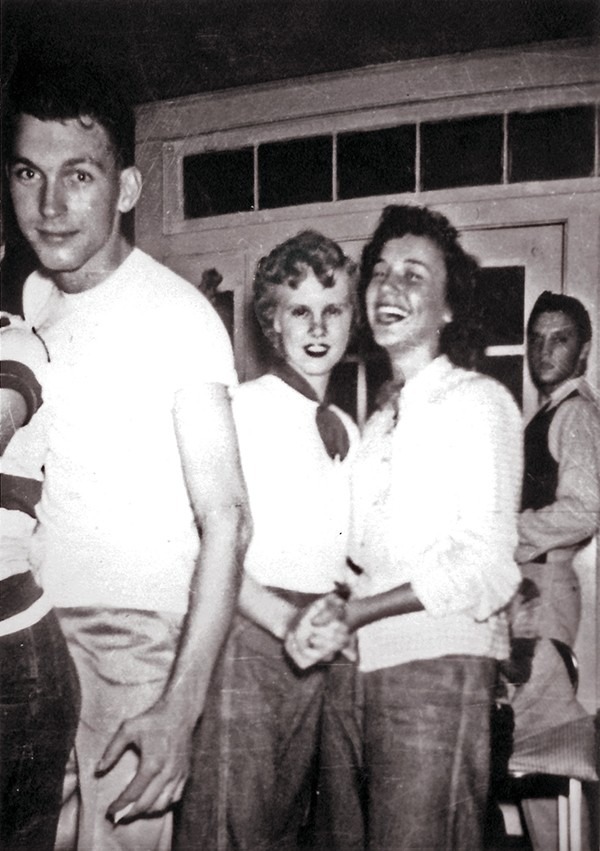

Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family

Blue Light Studio, which was located at Beale Street and Second Avenue.

Birthing Rockabilly

In 1948, Pop and Johnny Black met when their parents moved into the Lauderdale Courts, a low-income housing project located between Danny Thomas Boulevard and Third Street. Coincidentally, a young boy named Elvis Presley moved into the Courts with his family not long after.

As more families joined the community, the Lauderdale Courts became a creative environment that fostered the growth of the Memphis sound.

When the sun was out, a fresh-faced troupe would take Pop’s guitar and any additional instruments they could gather to the Triangle, a patch of grass at the northeast corner of the Courts now covered by I-40. Elvis, Pop, Johnny and Bill Black, Johnny and Dorsey Burnette, Paul Burleson, Charlie Feathers, Jack Earls, and whoever else found their way to the shade would sit beneath a towering sycamore tree for hours, trading licks and talking music.

The Blacks’ mother, Ruby, kept her door wide open for the teens.

“If it hadn’t been for Mrs. Black, we may have scattered to the four winds,” Pop says. “She’s the mother of rock-and-roll.”

In the 1950s, Memphis was still very much a segregated city. But the Courts was a melting pot of black and white. The teenagers had a common interest unmoved by race, and when country and blues rubbed shoulders, rockabilly was born.

“There were no distinctions,” Johnny says. “With musicians, there is no black and white. We’re all brothers. You don’t look down on one another. You’ve got a common denominator, and that’s music. That’s where it begins and ends.”

It wasn’t uncommon for other musicians to drop by the Triangle and join the jam sessions. At any given time, there could be 30 to 40 teenagers gathered in a circle, clothes dirty from a day’s work, joyfully passing their instruments around. But it was one local musician, about eight or nine years older than the typical group, who stopped by and changed the way they thought about music altogether.

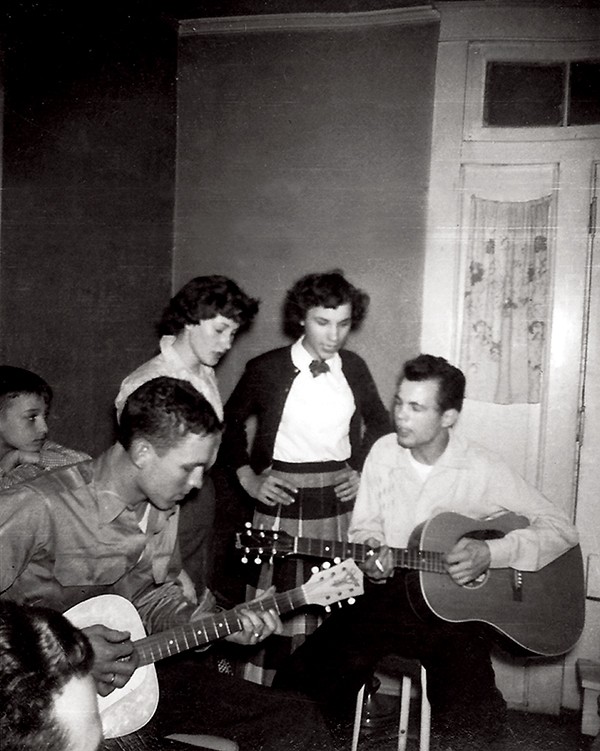

Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family

Jim Cannon (left) and Johnny Black (right) pick and sing at Cannon’s mother’s house at party for Cannon before he left for Korea. Carolyn Black (right), Vivian Miller (middle), and Joseph Buck Cannon (left) watch and sing along behind them. Johnny, who is left handed, would flip his guitar around and play it upside down.

“There were four or five of us sitting around one afternoon,” Johnny says. “We were playing a little country because that’s all we knew. Then a young black man came along and said, ‘Can I play your guitar?’ We had never heard anything like that. We were not only amazed, but we were delirious.”

Sometime later, they would hear the visitor playing on KWEM, a West Memphis radio station that featured many live performances from Mid-South musicians, and discovered his identity: He was B.B. King.

“Everybody who was going to be anybody was a nobody,” Pop recalls.

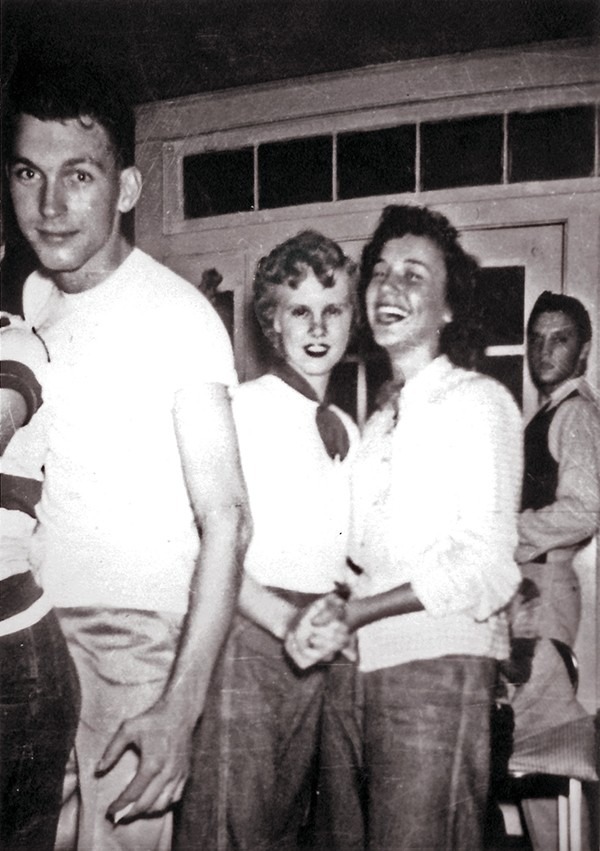

Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family

Jim Cannon (left), Jean Jennings (middle left), Johnny Black’s wife Carolyn (middle right) and Elvis (right) mingle at a party at Cannon’s mother’s house on Colby Street.

Johnny, three years older than Elvis, remembers the moment he realized Presley wouldn’t stay a nobody. One day in 1951, while a group of teenagers was throwing a baseball, Elvis and Johnny sat on the sidelines. Johnny had just purchased a used bass, and the two were picking when Elvis went into Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right.”

“The rhythm Elvis had was gigantic,” Johnny says. “You talk about tearing it up. I told Bill, ‘You’ve got to hear this guy.’ But it was about two or three years before they would get together.”

Catching The Train

Pop was drafted in 1953 to fight in the Korean War. He turned 21 years old in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. But even in Korea, Pop stayed connected to Memphis music. In a 1973 interview with the Memphis Press-Scimitar, he said, “Bill Black’s mother was always writing to me when I was overseas, telling me about ‘this little record’ Elvis had coming out.”

That “little record” was “That’s All Right” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” the double-sided single that launched Elvis into stardom in 1954.

Pop returned to Memphis in 1955 and started a band with Johnny and Dorsey Burnette called the Bluff City Six. They recorded a demo at Sun Studio with Bill Justis, whose song “Raunchy” was the first instrumental rock-and-roll hit, but nothing came of it.

“When I got back out of the service, everyone I knew who had any talent was on Sun or some other label,” Pop says. “I started chasing the rainbow, but it looked like the train had already pulled out of the station.” Still, he pressed on.

James and Peggy became Mr. and Mrs. Cannon in 1959, and got a family underway.

As Pop balanced the life of a traveling musician with that of a working, family man, he spent nearly every free moment in the studio. Chips Moman, who worked with Elvis and the Box Tops, produced two of his songs, “Evil Eye” and “Underwater Man.”

In 1966, Jim Cannon, then 25 years old, took six songs into Sonic Studios on Madison Avenue to record with Roland Janes. After numerous takes and hours of recording, Janes told him only one of his songs was any good, but that he needed a B-side. Determined, Pop went home and wrote until the early morning.

“I put pencil to paper and didn’t stop until I had, ‘Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy,'” Cannon says. “Roland could take a razor blade to tape when he was cutting a song, and you’d never know there was a stitch on it. He said ‘You’ve got a pretty good start on a song, but it’s not a song yet.’ He took part out of the chorus, put it on the front for an introduction and said ‘that’s going to be your A-side.’ Roland was a master musician.”

Pop pressed 1,000 records through his own WesCan Publishing company and sold them out of the back of his car. But in 1970, The Wilburn Brothers recorded a version of the song and released it through Decca Records. “Country Boy” received national airplay and made it as high as no. 4 on some radio charts. Author Dorothy Horstman named her first book, an anthology of country songs and the stories behind them, after it. Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn recorded a version of the song that was shelved due to a dispute between their labels. It has never been released.

When Pop was 36 years old, he found himself in a conference room with executives from United Artists, who asked him to write lyrics to four different song titles. Pleased with the outcome, they started to negotiate a contract until they found out his age.

“They liked all of them, but I didn’t get the contract,” Pop says. “They said it would take 10 years to make anything off of me, and they didn’t think they would get their money back. Everybody has got an opinion. They are what they are. If you believe in it, you stay with it.”

In 1973, Pop got lucky when Fretone Records founder Estelle Axton, a co-founder of Stax Records, signed him as an artist for the label. One of Fretone’s first singles was “Frumpy,” a Christmas song Pop wrote about a pet frog who overhears a group of children talking about being too poor to have a Christmas. The frog hops to the North Pole and works as Santa’s helper to ensure the children have gifts under their tree. James Govan also recorded a version of the song.

Looking back, Pop sees his time at the Triangle as his formative years. Underneath a sycamore tree on that patch of grass, a group of teenagers stumbled upon rockabilly — a genre that would become synonymous with Memphis.

Some, like Elvis and B.B. King, became known all over the world as forerunners of the sound. Others, like Pop, would scratch the surface — making a mark but never etching their name into history books. Still, Pop says his involvement is something he holds close to his heart.

“We were just playing what we felt,” Pop says. Before he finishes his thought, he takes a sip of coffee and realizes it’s cold.

Johnny continues for him.

“I don’t think we really realized [the impact we had],” he says.

Pop checks his watch and finds that we’ve been talking for more than two hours.

Johnny stands up from his recliner, and they hug again before pausing a moment. The room is silent. Pop looks at me, his smile appearing again.

“If it hadn’t been for the bunch of us over there, I don’t think there would be rock music,” Pop says. “Not then, anyway. Some went really big, others didn’t. But we followed our dreams. We gave it all we got.”

James Cannon performs “Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy”

and, “Slow Down”

Amazing Grace LLC

Amazing Grace LLC

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family  Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family  Courtesy Cannon Family

Courtesy Cannon Family