I was standing in the checkout line at Kroger when I saw the perfect tabloid headline: ANGELINA: TOO SKINNY TO CONCEIVE?

As a wordsmith, I appreciate its beauty in the same way a metalsmith might appreciate a katana. It is perfectly designed for its cruel purpose. Let’s break it down. “ANGELINA” defines the audience — women to whom Angelina Jolie is already a character in their minds, a beautiful, privileged woman with a complex personal life who is in every way more interesting and perfect than you. Then the colon delivers the warhead: “TOO SKINNY TO CONCEIVE?” Angelina Jolie is skinny. I wish I was as skinny as she is. But it’s bad that she is so skinny, because she can’t have a baby, which is the end-all, be-all of feminine existence. I have a baby, therefore I’m better than Angelina Jolie. But having the baby made me fat, and Angelina Jolie is so skinny, she has Brad Pitt. Or had, anyway. The beauty of the headline is that it allows women to feel both superior and inferior at the same time toward a famous woman, and then feel guilty about it. It’s a self-destructive psychodrama in five words, weaponized to make women pick up a trashy tabloid and read a complete nothingburger of a story.

I feel the same kind of grudging admiration toward that headline as I do toward The Girl on the Train. The film is adapted from the 2015 bestseller by Paula Hawkins, which was hawked as “The Next Gone Girl.” I didn’t read the book, but the film adaptation, directed by The Help‘s Tate Taylor with the screenplay adapted by Erin Cressida Wilson of Secretary, seems like it took “The Next Gone Girl” not as a description, but as marching orders. It’s a button-pushing, potboiler thriller, the same material that formed Alfred Hitchcock’s career. A female friend said it was “A Lifetime movie times 100, but I liked it. It’s a girl thing.”

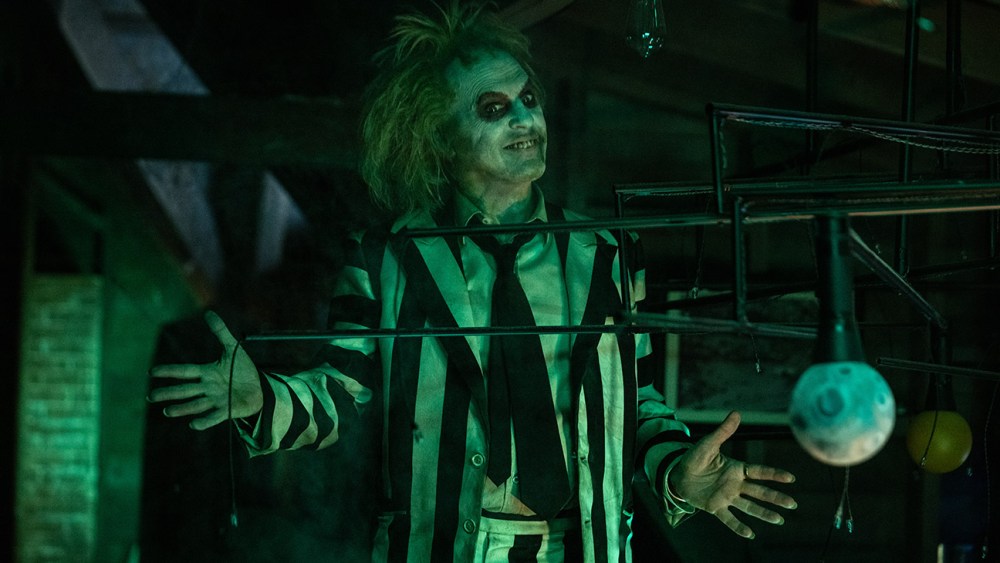

Emily Blunt goes off the rails as Rachel in The Girl on the Train.

Structurally, at least, The Girl on the Train is a lot more sophisticated than Mother, May I Sleep with Danger. (“No! You can’t sleep with danger! It’s literally called DANGER! Why are we even having this conversation?”) Taylor and Wilson take a fair stab at adapting Hawkins’ literary conceit of three narrators. There’s Rachel (Emily Blunt), the literal girl on the train, whom we meet in the midst of her commute to New York City. Despite the trappings of a successful professional life, she’s hopelessly depressed, living mostly through the fantasies she cooks up about the prosperous people she sees in the cookie-cutter houses along the train’s route. Then there’s Megan (Haley Bennett), the blonde bombshell who inspires Rachel’s envy with her perfect house, handsome husband, and seeming life of leisure. But our third narrator, Anna, has the one trapping of success that the other two lack: a baby. The only thing wrong in her idyllic Anthropologie catalog life is that her handsome, high-earning, baby-making husband Tom (Justin Theroux) has a crazy, drunk ex-wife, whom, we find out, just happens to be Rachel.

None of these three women are reliable narrators or very nice people, but the not-so-functioning alcoholic Rachel is the least reliable of all, because she spends most of her nights blackout blitzed. When she wakes up bloodied and half-clothed one morning and finds weird voicemails on her phone from Tom, she has no answers for Police Detective Riley (Allison Janney), who comes around asking why Megan has gone missing.

The Girl on the Train hops around both in time and point of view to slowly dole out plot points at the most disorienting moments, and usually I’m on board with that, but in this case, all the structural trickery just serves to highlight the characters’ cynical shallowness. Rachel, Megan, and Anna are like Angelina Jolie in the headline: blank hooks where target audiences hang their anxieties about wealth, status, body image, and fertility. Calling a film “manipulative” is not necessarily an insult (see: Hitchcock), but when the manipulation is as openly cynical as The Girl on the Train, it spoils the fun.