With all due credit to Stephen Colbert, the question must be asked: Was Hurricane Katrina a great disaster or the greatest disaster?

One thing is certain: For the insurance industry, it was apparently a pretty sweet disaster. In 2006, only a year after Katrina transformed the Gulf Coast into a 90,000-square-mile vision of the Apocalypse, the property-casualty industry posted a record $68 billion profit. That’s a whopping $19 billion more than the previous record of $49 billion, which was set in 2005, the year Katrina hit.

So how can companies that pay for property disaster post such stunning figures in the wake of the greatest property disaster in U.S. history? Hard work and hustle, that’s how. Industry spin has it that the big profits stem from non-coast-related growth in areas such as auto insurance and workman’s comp.

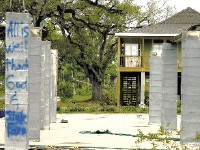

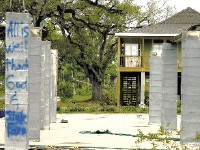

But if you ask the citizens of Bay St. Louis, Mississippi — where Katrina’s eye crashed ashore on August 29, 2005, demolishing a million-dollar fishing pier, the bridge to Pass  Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Christian, and most of the beachfront and flattening entire neighborhoods like a nuclear blast — they might tell you a different story. They might tell you that the insurance industry is poorly regulated and criminally exempt from antitrust legislation. And, judging from all the yard signs, they might just say insurance companies suck.

Visit Ricky’s Seafood Grill on I-90, where Bay St. Louisans gather for steak and shrimp. Or stop by the Mockingbird Cafe in Old Town for a spot of coffee. Talk to the off-duty casino workers having drinks at Clyde’s Bar or the Third Base. Anybody in South Mississippi can tell you that Katrina was the windless hurricane. It’s the joke everybody gets; the joke nobody gets tired of repeating.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Lots of people had hurricane insurance — which covers wind damage. Far fewer people had flood insurance. And therein lies the crux of the battle still being fought on the Gulf Coast between the insured and their insurance companies.

Chuck and Ellen Breath of Bay St. Louis count themselves lucky. The couple’s 185-year-old home overlooking the bay was completely obliterated, but it was insured by State Farm for both wind and flood damage, and, after being taken to mediation, the company paid. The Breaths received nothing for two rental properties that had been in the family since the 1920s. And nothing can erase the unpleasant memory of a visit the couple paid to the temporary field headquarters set up by State Farm in the wake of the hurricane.

The Breaths were met at a fortified gate by armed guards in black fatigues, who escorted them into the compound. Their visit was prompted by an unsettling phone call they received from a State Farm representative shortly after the storm, while the couple was staying with relatives in Florida.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

The caller wanted to know whether or not the roof of one of the demolished rental properties was sitting on its concrete slab. When Chuck affirmed that the roof was on the slab, the adjuster responded with a statement that Ellen Breath swears she’ll never forget. It prompted her to quit her job in order to fight State Farm. “We wouldn’t have gotten a lot of what we got if I hadn’t done that,” Ellen says. “And a lot of people can’t fight like that.”

According to the Breaths, the adjuster said that a roof on the slab means water, not wind, caused the damage. He added, “That means I don’t have to go see it.”

The Breaths held eight policies with State Farm, and they wanted proof that someone had gone to their property and surveyed the damage in person.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“Nobody could answer any of my questions,” Chuck says. “They said someone had been out to my property, but nobody could tell me if they had seen the tree on the ground between the roof and the floor.” The couple demanded to see whoever was in charge. They were told to leave by an angry supervisor. His words still make Ellen Breath flush with anger when she repeats them.

“He told us they didn’t need to see anything,” she says. “He said, ‘One piece of debris looks like every other piece of debris.'”

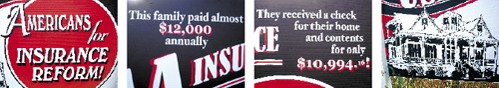

“Mississippi is still hot,” says Robert Hunter, of Americans for Insurance Reform, a national coalition of public-interest organizations that want to change the way the insurance industry operates. In a telephone interview from his office in Virginia, Hunter, a former Texas insurance commissioner and federal insurance administrator under Presidents Ford and Carter, describes the insurance industry’s attempt to dodge claims and offer policyholders pennies on the dollar as a battle of wills in a war of attrition.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“People get worn out,” he says. “They get tired of fighting and give up. Eventually, they take whatever they are offered.”

Hunter’s assertion is perfectly illustrated by the story of Pam Collins and Joy Panks, co-owners of the Twin Lights gift shop in Old Town Bay St. Louis.

“Our insurance company owed us $172,000,” Panks says. The last time she and Collins drove to Hattiesburg for mediation, a representative from their insurance company met them with a check for $55,000. The check was physically placed on the negotiating table, and the two women were given three chances to accept it. “The fourth time, they said they were going to pick it up,” Panks says.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“We were begging,” Collins confesses, thinking back over all the company’s previous offers. The bargaining started at $30,000, then went up to $40,000. “They said $55,000 was the last offer.”

Collins and Panks’ shop was wrecked by Katrina and wiped clean by looters. Their Cedar Avenue home in Pass Christian was completely destroyed — gone without a trace. They spent five months living in a borrowed camper parked in a friend’s yard in Louisiana. With little income and having to spend $30 a day in gas just to get into town to get in line for a FEMA trailer, they took the check. And they took out loans.

“You never think about starting over at my age and owing a million dollars,” Panks says, noting that she’ll be 93 when her Small Business Administration loan is finally paid off. “I guess they can come to Shady Farms to collect,” she jokes.

Humor, Panks says, is the only way to cope with being 58, deep in debt, and having to cash your IRA in order to pay $25,000 for a year’s worth of flood, property, casualty, and wind insurance that may or may not pay off when you need it.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Joy Panks and Pam Collins

In February, U.S. Senate and House leaders, including Mississippi senator Trent Lott and Mississippi congressman Gene Taylor, introduced legislation that would lift the insurance industry’s long-standing federal antitrust exemption. According to Lott spokesman Lee Youngblood, the senator never “studied insurance” until Katrina hit, and he was forced to take his own insurance company to court.

“This forced the senator to learn,” Youngblood said. Lott has traditionally been a free-market conservative — not a fan of excessive government regulation. After Katrina destroyed his beachfront home, Lott has vociferously championed lifting the insurance industry’s antitrust exemption, calling the companies “arrogant” and “mean-spirited” in their management of the Gulf Coast disaster.

“We’ve got [the insurance companies] demanding outrageous rate increases,” Lott recently complained at a hearing before the Senate commerce committee. “At the same time, the CEO of State Farm is getting a big pay raise for himself. So, from a PR standpoint, they ought to be ashamed of themselves.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Hunter stops short of accusing insurance companies of illegally colluding on their response to the devastation on the Gulf. “There’s no smoking gun,” he says. “There are no memos or telephone records that would indicate [collusion].”

Hunter says legislation lifting the antitrust exemption is important because of the cooperative behavior the industry engages in on a daily basis by using mutual consultants, vendors, and computer programs.

“It is hard to believe that all the companies have all done the same things,” Hunter says. “So there’s smoke. But to get to the fire — to [proof of] collusion — that will require lawsuits.”

In his March testimony before the Senate judiciary committee, Hunter argued for a repeal of the antitrust exemption, citing the “anti-concurrent-causation clause,” a confusing bit of contractual language that exempts insurers from paying for wind damage when flooding also occurs.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“The industry colluded to create a clause that no reasonable person could logically understand — to the detriment of consumers and the rebuilding efforts in the Gulf region,” he testified. “Wind seriously destroys a home, followed by a much later storm surge finishing off the home. … This is ‘no coverage,’ the industry alleges.”

“People trust their insurance companies,” Hunter says. “Most people don’t study the details [of their contracts].”

“My brand-new garage had 185-mile-an-hour wind strappings in each stud, and it was cut in half,” says Marian Taledano, a retired nurse. “It looked like someone had come through with scissors and clipped them like ribbons.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Taledano’s insurer determined that most of the damage to her historic home was caused by flooding, not wind.

Taledano’s husband, Jim, had retired from an administrative job with K&B Drugstores in New Orleans. After Katrina, the couple’s finances were stressed, and Jim took a job at a Lowe’s home center in Bay St. Louis. Shortly after returning to work, he died of a massive stroke. He was 62.

Marian Taledano recounts the horrors of a failed evacuation and being caught in the storm. She recites the troubles she and her husband had with their insurance company and remembers the first two months of the recovery, when they lived outside with no electricity or fresh water and would grab a bar of soap and stand under the gutters when it rained. She blames her husband’s death on stress. And he wasn’t the only retiree Katrina forced back into the workplace. Or the oldest.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“I never thought at 73 I would be driving a van for the YMCA’s adolescent-offenders program,” says Ed Young. Like so many others, Young found himself in a wind-versus-water dispute with his insurance company. Like so many others, he didn’t have flood insurance.

“I was in a no-flood zone,” he says. “Bay St. Louis is 27 feet above sea level, and the insurance agents wouldn’t even talk about flood insurance. Everything was measured against Hurricane Camille in 1969, which wiped out the whole area. But it didn’t flood.”

It would be difficult to accuse Young of not planning well for the future. To supplement his retirement savings, he invested in rental properties. And they were wiped out in the storm. Ed’s wife, Sylvia, was on the verge of retirement and in the process of selling her business, Bon Temps Rouler, a successful bridal, formalware, and costume shop in Old Town Bay St. Louis, when Katrina hit.  Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Marian Taledano

Sylvia’s building survived the storm but was coated in several feet of mud. She lost a significant portion of her stock, as well as the potential buyer. The Youngs have since converted what remained of Bon Temps Rouler into the Antique Maison, a store selling used furniture, curiosities, and collectibles.

Sylvia repeats the same phrase whenever she talks to the media: “We needed so much help. But the government couldn’t, the insurance companies wouldn’t, and, if it weren’t for the faith-based groups that have come in to help us rebuild, I don’t know what we would have done.”

At a recent meeting of the Bay St. Louis Historical Society, Charles Gray, the society’s director, happily announced that his building’s floor had finally been leveled and that the newly replaced roof that leaked like there was no roof had been replaced by a newer roof that didn’t leak. On a less happy note, he also announced that the City Hall building remained closed pending an insurance settlement.

Used-book dealer Patti Fullilove has eyewitnesses who saw tornadoes in her neighborhood, but to settle her property claim, she had to join a class-action suit.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Sylvia and Ed Young

And 74-year-old Joan Merrill tells how she received a call from her insurance company claiming — illegally — that the policies on her severely damaged rental properties would be canceled if the properties continued to go unoccupied.

Everyone in Bay St. Louis has an insurance story to tell, and, with few exceptions, they are not happy ones.

Still, there are reasons for Bay St. Louisans to be optimistic, especially since the opening of the bridge to Pass Christian. The city still doesn’t have a proper grocery store, but visitors to the bustling Hollywood Casino and Hotel are advised to reserve their rooms well in advance.

Businesses that are open are busy. Searching for a silver lining in the long dark cloud of Katrina, Bay St. Louis city councilman Jim Thriffiley points out that fast-food and retail workers have become highly prized commodities in parts of the Mississippi coast. That, he says, results in hiring bonuses and above-average pay in traditionally low-paying sectors.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Thriffiley theorizes that many Bay St. Louis residents who worked $8-an-hour jobs before the storm took similar jobs wherever they landed and didn’t come back. Those who did return, he suggests, took higher-paying jobs doing recovery work. “Everybody is looking to hire people,” Thriffiley says. “From the shipyard on down — all trades, all skills. Everyone is having a hard time finding employees.”

People who live here describe Bay St. Louis as “a place apart.” In spite of the turmoil they’ve gone through, they believe that the Gulf Coast will recover and flourish as casinos expand and improve their waterfront holdings and as developers acquire land and resurrect demolished neighborhoods.

Even on the insurance front there is some hope. In a recent critique of Allstate and State Farm insurance companies, Senator Lott reaffirmed his determination to see justice done on the Gulf, declaring, “I’m prepared to kick [the insurance companies’] fanny until the last day I’m alive on this earth, because they have mistreated too many people.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

On May 4th, Richard “Dickie” Scruggs, a Mississippi attorney who continues to fight the insurance companies and win, electrified a group of New Orleans-based lawyers by telling them in plain, unvarnished language that the insurance companies’ instructions to their adjusters to “max out” water damage was “a license to steal.”

And yet, for all the genuine optimism that exists, there are many reminders the Katrina’s ill wind is still blowing on the Gulf. For every business that’s open and busy, it seems there are two bombed-out-looking buildings lying empty, broken beyond repair. For every home being rebuilt, there’s a neighborhood dotted with temporary housing and signs reading, “For Sale/Reduced.”

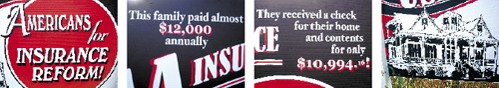

On an empty lot along the gravel path that passes for Bay View Road, a sign bears a picture of the ornate 19th-century home that once stood on the property. “This family paid almost $12,000 annually [in insurance premiums to USAA Insurance],” it reads. “They received a check for their home and contents for only $10,994.16.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

The sign was placed by Kevin and Sherrye Webster, who moved to Nashville after the storm. They say they are still fighting a lawsuit against an insurance company that is trying to pay them pennies on the dollar.

Katrina, the “windless hurricane,” is still blowing. And Bay St. Louis is still in the center of the storm.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis