“Memphis’ Stonewall”

Halloween was once the only time a man could get away with dressing in drag in Memphis. That’s because a 1967 city ordinance prohibited “any person … to appear in public in the dress of the other sex.”

Vincent Astor Collection

Vincent Astor Collection

Bill Kendall

And that’s why Bill Kendall, manager of the Guild Theater, cleverly planned the city’s first drag show for October 31, 1969. He still had to walk a fine line, so for an added layer of protection against a possible police raid, he made sure to pack the Guild (now the Evergreen Theatre) with plenty of real women — gussied-up females.

John Parrott remembers heading to the Guild that Halloween, but he stopped off at a bar first. People inside were dressed like they too might be heading to the theater, but they weren’t.

“I talked to some folks who said, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t go there tonight,'” Parrott remembers. “There’s a chance of it being raided.”

Parrott wasn’t intimidated — it was going to be his first-ever drag show — but he understood why others might be.

“Go back and look at the press coverage in the early 1960s,” Parrott says. “If a place was raided — and that was what they feared — the papers didn’t hide anything. If you were caught in a place like that, they would print your name, your place of employment, your age — everything. If you got caught in a raid, you got fired. That was almost a certainty. That’s what they were afraid of.”

But the Guild wasn’t raided by police that night. In fact, Parrott says the evening was “euphoric.”

That show — which happened 50 years ago, this Halloween — was a touchstone for the Memphis gay community. The event, which was called the Miss Memphis Review, cracked open the city’s closet door and set a path to greater acceptance for those who would follow. It was the city’s first public pride celebration. Historian Vincent Astor calls the event “Memphis’ Stonewall.”

To honor its impact, a marker will be erected on the site on October 31st — the city’s first acknowledgement of its gay history.

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Miss Memphis Review, held in the Guild Theater (now the Evergreen), was the city’s first public gay pride event. The event, held on Halloween night in 1969, was more pageant than drag show — and it was a huge first step for the LGBTQ community.

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

“Absolutely Unbelievable”

Parrott remembers the show got started late, maybe 10 p.m., or even midnight. Edd Smith, the emcee, got up on the stage, made the proper announcements, and the pageant began. Parrott says it was just that, a pageant, not really a drag show.

“There was a piano, a Hammond organ, and a palm tree, painted in Day-Glo colors with a black light,” Sharon Wray (an owner or partner in many gay and lesbian bars in Memphis) told Astor.

“Drag was done live with piano accompaniment,” Astor wrote in a 2017 post on the Friends of George’s website, “and much of it was camp and comedy.”

Parrott says a “good many were dressed up in tuxedos,” adding that “it was pretty packed. The euphoria was absolutely unbelievable. There were some who got scared and didn’t go, but the ones who did go realized exactly what they were doing.”

One by one, the 18 contestants (Pearl, Sandy, Dee Dee, and Brig Ella among them) came out dressed in evening gowns or whatever the pageant category demanded. There were waves of applause, hooting and hollering, and torrents of laughter.

While those at the Guild may not have known they were making history that night, they were certainly aware they could get in trouble. In addition to the city’s cross-dressing ordinance, another city law prohibited acts “of a gross, violent, or vulgar character.” This was aimed at same-sex dancing.

No doubt, such specific laws targeting gays still worried pageant-goers, no matter how euphoric the revelry. That’s where Kendall’s precautions — and timing — paid off.

“It was Halloween night, and [the police] would have to arrest people at bars all over town for cross-dressing,” Astor says. “That was one thing that saved them. There were also a lot of RGs (Real Girls) in costume. We know the differences between a DQ, a drag queen, and an RG.”

The hope was that the cops might not.

A Quick Evolution

The pageant was a giant step out of the shadows for the Memphis gay community. A similar pageant had been held the year before, but it was at a private party in Victorian Village’s Lowenstein-Long house, Astor says.

The fact that no one was arrested at the Guild the following year emboldened the community. Drag bars began to pop up around town, including Frank’s Show Bar and George’s Infamous Door. All of this happened even though the word “gay” wasn’t used, Astor says, “because that would just have been more fuel for the fire.”

In 1971, four men were arrested for “female impersonation,” according to a timeline of Memphis gay history compiled by OUTMemphis. They were arrested at George’s Infamous Door (as was owner George Wilson), but the charges were dismissed as the court failed to prosecute.

In 1974, Tennessee’s obscenity law was deemed unconstitutional, thanks to the perseverance of Kendall, who’d been repeatedly indicted for showing a variety of “obscene” foreign films and art films at the Guild.

By 1975, Memphis had five gays bars — Tango, Psych-Out, B.J.’s, Entree Nuit, and George’s. Five people leaving one of the bars that year were arrested for solicitation, three of them charged with “female impersonation.” The charges were dropped, but instead of taking a plea deal, they fought the case in court, won, and had their records expunged.

That same year, the group The Queen’s Men took over what they were now proudly calling the Miss Gay Memphis pageant. The first issue of Gaiety, the city’s first LGBTQ newspaper, was also published in 1975.

In 1976, the Metropolitan Community Church organized and welcomed “gays and straights of all faiths.” The city’s first public pride event — “Gay Day at the Park” — was held in Audubon Park. And the first Gay Student Association was founded that year at what was then Memphis State University.

Within seven years of that first Miss Memphis Review pageant at Midtown’s Guild Theater, several big steps had been taken.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Mark Jones and Vincent Astor

The Legacy of Stonewall

Rallies, parades, and other commemorative events marked this year’s 50th anniversary of the police raid on New York City’s Stonewall Inn — and the several days of violent conflict and protests that followed. It was a tumultuous chapter in gay history but one that’s now seen as a pivotal moment for LGBTQ rights.

Astor was in New York for the celebration and says, “I haven’t seen so many rainbow flags in all my life.” Astor says the Miss Memphis Review, staged just a few months after the Stonewall unrest, was “our Stonewall. That’s what we’re celebrating.”

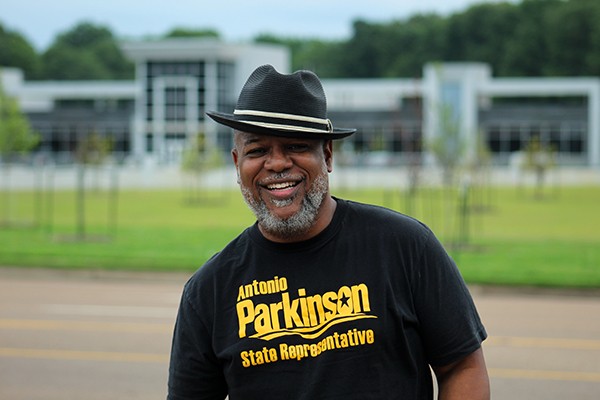

The driving force behind the new marker has been veteran Memphis filmmaker Mark Jones. Jones says Kendall was a “flamboyantly gay man” and “a hero.”

“He did a lot for Memphis and was a very early LGBTQ pioneer,” Jones says. “The Miss Memphis Review was an important LGBTQ event in those early, pioneer days.”

When the marker is put up next month, it will be the first physical commemoration of Memphis’ LGBTQ history, and the second such marker in Tennessee. Nashville erected a marker to commemorate its historic gay bars last December.

The Memphis marker was unanimously approved by the Shelby County Historical Commission. Jones says he was “happy and surprised” there was no dissent. The only discussion was over grammar. And one member insisted the sign have the word “gay” on it, to ensure people would know its true significance.

“Let’s be honest, there’s been gay folks getting together since 1819 in Memphis, but it’s all been hush-hush and in secret,” Jones says. “[The Miss Memphis Review] was the first time it happened in public. It’s the 50th anniversary. So, we need to honor that.”

Astor and Jones will do so with an unveiling ceremony for the marker at the Evergreen Theatre on Thursday, October 31st at 6 p.m. Inside the Evergreen, there will be artifacts from the Miss Memphis Review that Astor has collected.

What follows will be a “moveable feast,” he says. It will start at the soon-to-be-open Dog Houzz, a gourmet hot dog restaurant on the former site of the Metro gay bar. The party will then move to Dru’s Place for a special drag show at around 8:30 p.m.

Astor says all events are open to everyone, but he especially welcomes anyone who was present for the 1969 Miss Memphis Review.

Jones hopes the marker and the event are the first of many celebrations of Memphis gay history. “We need our history told,” he says. “We need our history honored, and we need it spread out across our city.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Jeremy and Matthew Thacker-Rhodes

Jeremy and Matthew Thacker-Rhodes

Taking Care of Business

When I was assigned to write a profile of Jeremy and Matthew Thacker-Rhodes, my colleague Toby Sells told me, “These guys have a lot of irons in the fire.”

He wasn’t kidding. They founded Pride Staffing Agency. They are part of the team behind the Downtown jazz lounge Pontotoc. They own their own barbershop, Baron’s Man Cave. And they’re preparing to start yet another business that provides merchant services such as credit-card processing, point of sale technology, and consulting.

“One thing leads to another when you open up a business and you have success. You start networking, meeting people, and then opportunity comes to you,” says Jeremy. “We both have the type of mindset that just thrives off the stress.”

Jeremy is from Arkansas; Matthew is from Alabama. The couple had a six-month, long-distance relationship before coming together for good at the 2013 Memphis in May World Championship Barbecue Cooking Contest. They were married in San Francisco in April 2014 and are currently parenting three children, the youngest of whom just turned two.

Jeremy says their relationship works because their personalities complement each other so well. “[Matthew] is my balance, if that makes sense. We have almost two totally different types of personalities, but he has strength I don’t have, and that makes me stronger. And I feel like I do the same with him.”

Jeremy says they have found acceptance in Memphis they could not find in their rural hometowns. “One of the reasons I came to Memphis was to come to a Southern city and to start fresh being who I was. I still struggled with whether people would accept that, even in the business community. I’ve had clients that I’ve lost for being part of the LGBT community. But you reach a point in life where, I’m tired of trying to pretend to be someone I’m not, and it’s time to be myself. Life is short. I am who I am, and I’ve been this way since birth, and I can’t change who I am. You get to a point where you own who you are when you’re gay. And that’s something to accept when you grow up very religious in the South and in a small town.

“Moving to Memphis gave both of us the opportunity to come out of the box and be who we are and realize that we can be accepted for who we are and not be judged and still own our own businesses. Do we still catch stuff from people? Absolutely. Some people are going to be close-minded till the day they die, and you can’t do anything about it. Now does it affect some volume of business? Yes, but I think it balances out because you have others who love to deal with you because you are who you are. … It doesn’t matter if you’re gay or straight or whatever. Being successful owning a business is all about doing things ethically, doing things right, delivering on what you say, and just keeping your nose to the grind and staying focused. That’s what makes you a success. It’s not about being gay or straight or whatever that makes you successful, it’s about who you are as a person, and being gay is just a small part of who I am.” — Chris McCoy

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Kayla Gore

Kayla Gore

Human Rights Warrior

Kayla Gore wrote last year that the average life span of a transgender woman of color is 35. She just celebrated a birthday — her 34th.

“It kind of makes you live your life in your own lifestyle, and for a person like me it’s almost impossible to not be visible,” Gore says. “A lot of advocates are saying our visibility will get us killed because the number of trans murders is rising every year.”

Twenty-six transgender people were murdered [in the U.S.] in 2018, according to the Human Rights Campaign. Eighteen transgender people have been murdered so far this year, Gore says. The majority of these were black transgender women murdered by acquaintances, partners, and strangers, with some cases showing a clear anti-transgender bias.

If advocates ever suggested that Gore should keep a low profile because of the murders (or anything else), she didn’t listen. Earlier this year, she stood before a podium in Nashville, telling the press, state lawmakers, lobbyists, advocates, and anybody else who would listen that they didn’t get to define her.

“I have been a woman my entire life,” Gore said. “However, the state of Tennessee refuses to recognize my identity and forces me to carry incorrect identity documents.”

Gore is the lead plaintiff in a case challenging a state law prohibiting transgender people from changing the gender marker on their birth certificates. The suit is still pending.

While the birth-certificate lawsuit is a high-profile moment for Gore, it’s hardly the beginning of her activism work. She arrived in Memphis — homeless — nine years ago. She found other homeless, transgender people, and they invited her to a meeting for Homeless Organized for Power and Equality (HOPE). At the time, the group was fighting against housing organizations that preyed upon the homeless and those with mental health issues.

“That made me so passionate,” Gore says. “There are actually people out here doing things about the things we need to do things about. It lit a fire in me.”

That fire was fueled with some wins. She helped to secure federal funds for the chronically homeless through the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center and helped shut down some of those organizations preying upon the homeless.

For the last six months, Gore has been working as the Southern Regional Organizer for the Transgender Law Center through Southerners on New Ground (SONG), a social justice advocacy organization supporting queer, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people primarily in the South.

About two years ago, Gore started her own group, My Sistah’s House. It provides a place for transgender, gender non-comforming adults who have been released from incarceration and are experiencing homelessness or anti-transgender violence.

When asked about the climate for transgender people in Memphis right now, Gore says, “It’s bad, nearing a storm.”

“On July 1st, [the state began] criminalizing trans folks for using restrooms,” Gore says of the “indecent exposure” bill passed by state lawmakers this year and signed by Governor Bill Lee in May. “If someone complains and calls the police, [transgender people] can be jailed, tried, and put on the sex offender registry just for using the restroom. It’s something that trans folks have never had a problem with.”

But Gore says she is hopeful, noting a “few good candidates” will be on the ballot this year in Memphis. “I’m always optimistic about the future because I see the headway we’re making.” — TS

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Diane Duke

Diane Duke

A Friend for Life

Diane Duke moved to Memphis three and a half years ago to take the reins of Friends For Life. “When I was in Los Angeles, I’d been working around HIV issues,” she says. “I was looking at some job openings, and, from my time working at Planned Parenthood, sexual health is something that’s important to me. Looking at Memphis, the numbers I saw about the high rates of HIV and the ways that it was broken down made me wonder what was going on here, as far as why this area has such a high rate of new infections.”

Duke, who has three decades of nonprofit work under her belt, was born in Virginia to a father who was in the Coast Guard. Growing up, she traveled around the South before settling in Oregon. “I knew what the South is, as far as the Bible Belt and the conservatism and how that impacts what’s going on with HIV. Coming from Los Angeles, where people are HIV-positive and there’s no stigma, I had an understanding that there was a lot of work to be done in Memphis. With all the medical advances that we have saying that people are still dying of AIDS and that new transmissions of HIV were so high, I knew this would be a place where my work would be very fulfilling. And that has been the case. I I love it here. I love the work that I do. I love the people I work with. And I love the community.”

Friends For Life, which was originally organized in 1985 as the Aid To End A.I.D.S. Committee, is one of the oldest HIV-centric organizations in the South. Duke leads a team of 50, which serves more than 2,700 people annually. Their goals are to prevent new HIV infections, help people with HIV stay on their treatment plans, reduce and prevent homelessness among those who are living with HIV, and educate the Mid-South about HIV prevention and the treatment and spread of the disease.

“It’s difficult because sometimes you want to bang your head against the wall,” Duke says. “You just wanna say, ‘Hey folks, all you have to do is take a pill. Just get tested. Find out about this.’ But because of the stigma, where people get thrown out of their house, thrown out of their faith communities, thrown out of their friend community, it’s not safe if people find out that they are HIV-positive. There’s just so much work to be done to really change the stigma and the community’s view around HIV and LGBTQ issues.”

But with recent medical advances and a robust organization that is expanding its outreach to the hard-hit African-American LGBTQ community, Duke says she is optimistic about the future. “I’m a dreamer. People call me Pollyanna.” — CM

Photographs by Maya Smith

Photographs by Maya Smith

Vincent Astor Collection

Vincent Astor Collection  The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries  The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries  The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries

The Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, Special Collections Department, University of Memphis, University Libraries  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Lambda Legal

Lambda Legal