“Previously on” the Flyer‘s TV review page: Contemporary scripted TV is our equivalent of masterpieces of fine art. Our museums and galleries are HBO, AMC, Showtime, the basic networks, FX, and Netflix. The Sopranos is a Caravaggio; Breaking Bad is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Triumph of Death; Mad Men is an Edward Hopper.

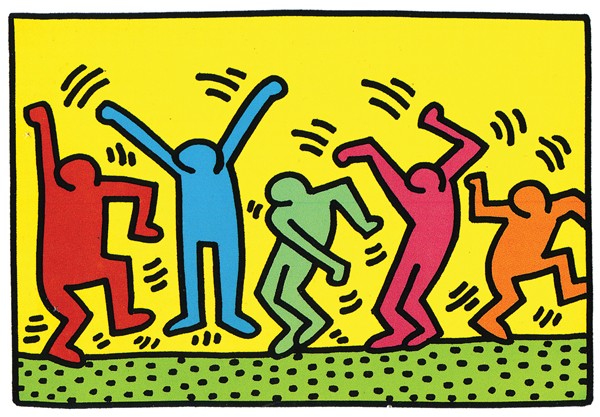

NBC’s Parks and Recreation is a Keith Haring: an energetic, animate, joyous pop dance — a celebration of life with social commentary encoded in the brushwork.

Haring’s work: a celebration of life with social commentary in the brushwork

At the heart of Parks and Recreation are Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler) and Ron Swanson (Nick Offerman), the deputy director and director, respectively, of the parks and rec department in the fictional small town of Pawnee, Indiana. A most cheerful, well-intentioned, and indefatigable soul, Leslie serves the town she loves with a civil-service glee rarely found in nature — she wants to help everybody. A political feminist, she displays photos of the likes of Hillary Clinton and Madeleine Albright in her office.

To the naked eye, Leslie and Ron could not be more different. He’s a gruff, masculine outdoorsman and devout libertarian who is in charge of Pawnee’s parks department because that’s the best place he can ensure that the citizens will not begin to rely upon government services. Ron would like nothing more than to spend his time self-reliant in the woods with a whittling knife in one hand, a bottle of dark liquor in the other, and a fire at his feet.

What Leslie and Ron lack in shared perspective they make up for in mutual, sometimes begrudging respect. They genuinely like each other and put up with each other’s peculiarities because they are both good people, and they recognize that quality in one another. Their differences are diminutive compared to their commonalities. Writ large, this is the quality that sets Parks and Recreation apart from any other show: a seam-splitting generosity and humanistic altruism for all mankind.

Though considerably political in theme, Parks and Rec is not divisive in delivery. Most anybody anywhere on the left-right spectrum can find something or someone to relate to. But, the positive slant shouldn’t be mistaken for naiveté on the part of the creators, Greg Daniels and Michael Schur. Because, though the show is always looking for the good in people, Pawnee is filled with a rabble of narrow-minded, mean citizens who usually don’t act in their own best interests because they’re too dumb to identify them. This jibes with reality, and so Parks and Recreation is on some levels not just an infinitely enjoyable show but also a counterrevolutionary one in American television. It’s the good twin to the other inarguably great half-hour of the past few decades, Seinfeld. Parks and Rec never tires of trying to find the good in people, even when individuals prove unworthy again and again. Meanwhile, Seinfeld never had anything good to say about anybody.

That Parks and Recreation has maintained its spirit of goodwill toward man despite the coterminous real-world rancorous politics is all the more remarkable; 2009 saw the birth of both Parks and Recreation and the national Tea Party movement. As the axiom goes, “All politics is local.” Parks and Recreation, set in the calcified strata of small-town government and a myopic populace, somehow still manages to make one believe that maybe America is going to be all right, after all.

The terrific Parks and Rec cast prepares for its final season.

The ensemble cast is expertly designed and deployed; no two characters serve the same purpose, and no two inter-character relationships play out the same: Ann Perkins (Rashida Jones), Leslie’s BFF, a pragmatic nurse who wears her beauty uncomfortably; Tom Haverford (Aziz Ansari), a metrosexual serial entrepreneur whose schemes frequently put him in over his head; April Ludgate (Aubrey Plaza), an unexcitable hipster who disdains everything and everybody (with a heart of gold); Andy Dwyer (Chris Pratt), a goofy underachiever who gleefully dives like a puppy into every scenario; Donna Meagle (Retta), a pop culture diva who knows what she likes and usually gets what she wants; Chris Traeger (Rob Lowe), the literally flawless city manager who uses extreme positivity to hide the fact that he’s freaking out about aging; and Jerry Gergich (Jim O’Heir), the oft-abused bureaucratic functionary who can’t get out of his own way.

Last but hardly least is Ben Wyatt (Adam Scott), the love of Leslie’s life, nerdy and competent, deadpan and romantic. The relationship between Ben and Leslie is surpassed in charm only by Leslie’s platonic one with Ron. If every embellishment was stripped away from the show, what would remain are Leslie and Ron — a chaste kind of opposites attract.

Parks and Recreation is the true heir to two of the other greatest half-hours of all time: The Andy Griffith Show and Cheers. All three are regionally attentive, smartly written, finely tuned sitcoms about the family we make out of our friends and loved ones, except Parks and Rec has the added benefit of being able to be more topically adventurous and demographically diverse. Plus, the only true villain in Parks and Recreation, Pawnee’s neighboring town of Eagleton and its residents, is the geospatial mash-up of Mount Pilot and Gary’s Olde Towne Tavern.

The difference is that Cheers and Andy Griffith never made me emotional, whereas Parks and Recreation is so moving it makes me cry on the regular. The show is coming to an end; its seventh season is its last. Perhaps it’s where I am in life or just appreciating where it’s taken me, but this ending is going to make for a tough goodbye.