In his May 17, 1999 review of The Phantom Menace, Roger Ebert wrote “The dialogue is pretty flat and straightforward, although seasoned with a little quasi-classical formality, as if the characters had read but not retained “Julius Caesar.” I wish the “Star Wars” characters spoke with more elegance and wit (as Gore Vidal’s Greeks and Romans do), but dialogue isn’t the point, anyway: These movies are about new things to look at.”

Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker

Ebert gave The Phantom Menace 3 1/2 stars. Had he been around to review The Last Jedi, he would have had to add several more stars to his scoring system.

In 1999, it had been 16 years since Return of the Jedi, the final installment of George Lucas’ epoch-defining space opera. Those of us who had been fans from the beginning never thought we would see another Star Wars movie, and the anticipation was intense. Ebert, like everyone, was dazzled by the visuals, which heralded the maturation of CGI. But the elemental, mythological storytelling that had made Star Wars a cultural phenomenon in 1977 was missing, the dialog was awful, and the acting ranged into the embarrassing. The prequels were wildly uneven, but there were still hints of what we knew Star Wars could be.

The Last Jedi feels like the fulfillment of that missed potential. It is the most visually stunning of the eight Star Wars films, the characters speak with the elegance and wit that Ebert wanted, and the acting is often outstanding. It is exciting, funny, cute, tense, melancholy, smart, goofy, unexpected, and occasionally profound. The opening night audience at the Paradiso burst into applause four or five times. I cried through two Kleenexes. But most importantly, The Last Jedi is fun. In a year with some astonishing big budget misfires, it represents the pinnacle of 21st-century Hollywood filmmaking.

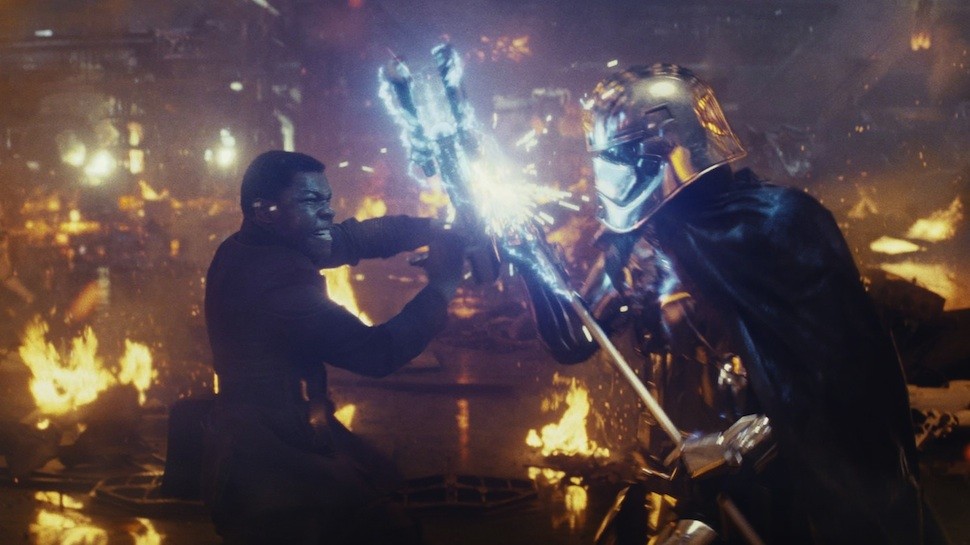

John Boyega and Gwendoline Christie do battle in The Last Jedi.

The success of this film can be credited to two people. The first is writer/director Rian Johnson, whose 2005 debut film Brick is an indie classic, and who directed one of the greatest hours of television ever produced, “Ozymandias”, the penultimate episode of Breaking Bad. Johnson is clearly a first generation Star Wars geek, but he is skilled and clear-eyed enough to craft a universal story. Johnson’s talent for visual composition is in the same league as Spielberg and Hitchcock. Lucas’ prequels were overloaded riots of color and movement. J.J. Abrams’ The Force Awakens was successful when it aped Lucas’ superior 1970s style. Johnson’s frames are mathematically precise without succumbing to Kubrickian coldness. He’s not afraid to swoop the camera around, but there’s a reason for every movement. From the clarity and acumen of his action scenes, he’s been studying the lessons of Fury Road. But where The Last Jedi exceeds all previous Star Wars movies—and 99 percent of other movies as well—is the use of color. Deep reds, lustrous golds, inky blacks, and vibrant greens reflect and reinforce the characters’ emotions.

Daisy Ridley faces the Dark Side in The Last Jedi

In the tradition of the Saturday morning sci-fi action serials like Zombies of the Stratosphere that inspired Star Wars, Johnson’s screenplay is full of red herrings, hairpin reversals, and betrayal. He was given too large a cast and too complex a situation, and he not only made the most of it, but left the story better and tidier than he found it. Ebert’s Phantom Menace review closes with these lines: “I’ve seen space operas that put their emphasis on human personalities and relationships. They’re called Star Trek movies. Give me transparent underwater cities and vast hollow senatorial spheres any day.” The Last Jedi delivers on both fronts in a way the Abrams’ nü-Trek simply doesn’t.

Not only that, but Johnson can work with actors like Lucas never could. One of the miracles of the original Star Wars is that Lucas, preoccupied with the various technical disasters unfolding around him, largely left the actors to their devices. And yet Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, and Mark Hamill managed great performances. In the prequel era, it became quickly obvious which actors could wing it, like Ewen McGregor, and which ones depended on dialectic with the director, like poor Natalie Portman. Not all actors in The Last Jedi are created equal, but you get the sense that Johnson has set everyone up to give the absolute best performance possible. Daisy Ridley’s physicality carried her through The Force Awakens, but in The Last Jedi she seems more relaxed and playful, even if her default mode is still “scary intensity”. Oscar Issacs stretches out into Poe Dameron, and by the end of the movie his look is echoing Han Solo’s Corellian flyboy, pointing toward the Harrison Ford-shaped hole he’s filling in the cast.

Kelly Marie Tran and John Boyega

John Boyega’s Finn is unleashed with a new partner, Rose, played by comedian Kelly Marie Tran. Their chemistry is near perfect, and their subplot bounces them off Benicio Del Toro as DJ, delivering a crackerjack turn as one of the shady underworld figures Star Wars loves. Lupita Nyong’o’s Maz Kanata makes the most of her extended cameo. I hope we see more of her next time around, but for now it makes me smile that the phrase “Maz flies away in a jetpack” must have appeared in the screenplay.

Adam Driver as Kylo Ren

Comic book movies are ascendant right now, but the biggest lesson the Marvel and DC teams can learn from The Last Jedi is that you need quality villains to make epic stories work. Johnson’s excellent script gives Adam Driver, a fantastically talented actor, the juiciest role, and he grabs it with both hands. Caught between Supreme Leader Snoke, Andy Serkis’ preening, snarling big bad, and Domhnall Gleeson’s General Hux, the latest in a long line of arrogant Imperial Navy twits, Kylo Ren comes into his own as a complex, conflicted character. In battle, Kylo is a lupine predator, but his eyes are haunted. The Last Jedi is a sprawling ensemble piece, but Driver and Ridley are the real co-leads.

Carrie Fisher as General Leia Organa

Most of the audience’s tears are reserved for Carrie Fisher, who died a year ago, shortly after completing her work on The Last Jedi. Perhaps it is hindsight, but Fisher looks frail and vulnerable as General Leia Organa, her physical appearance reflecting the increasingly desperate straights of the Resistance she leads. But there is fire in her eyes and steel in her voice, and the bravado sequence Johnson designed for her where she at long last manifests her Force powers drew gasps and cheers. We can all only hope to go out on such a high note.

But if The Last Jedi belongs to any one actor, it is Mark Hamill. Luke Skywalker has been both a blessing and burden to Hamill, who at heart seems to be an amiable geek who would be perfectly happy doing cartoon voice acting for the rest of his life. (He is the best Joker ever, and I will fight anyone who disagrees.) Hamill gives the performance of a lifetime as a man who finally broke under the weight of his own legend. The boys who grew up idolizing Luke Skywalker are men now, and Hamill’s performance is full of the regret, hard-won wisdom, and grit that age brings. Luke, the focus of the original Hero’s Journey, provided generations with a mythical model of how to grow up. Now, he gives a model of how to pick yourself up and keep going through a life that didn’t turn out quite like you thought it would.

Daisy Ridley and Mark Hamill

The second person on whom the success of The Last Jedi depends is Kathleen Kennedy. The Lucasfilm honcho is simply the best producer working today. She’s driving the biggest bus in the business, and succeeding spectacularly where so many others fail. Kennedy has practically infinite resources at her disposal, but so did the producers in charge of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, Transformers: The Last Knight, The Mummy, X-Men: Apocalypse, and so many other corporate vomitoriums of 2017. The key to producing good movies—and really to any artistic endeavor—is creating a healthy process. This is something that Kennedy, alone in contemporary Hollywood, seems to understand. This year alone, she fired the directors of not one but two Star Wars movies while they were shooting, an unprecedented move that prompted grumbling in both the fan community and the swank brunch spots of Hollywood. But even before The Last Jedi premiered to boffo box office (As of this writing, earning more than $160 million in TWO DAYS), she gave Johnson the deal of a lifetime—a whole Star Wars trilogy to himself. She saw Johnson’s professionalism, knew what she had in the can and wanted more of it. And if you spend 152 minutes in the Star Wars universe in the coming days and weeks, you’ll want more of it, too.