Gone Girl is based on a bestselling crime novel by Gillian Flynn, who also wrote the screenplay. With its byzantine plot, morally ambiguous characters, and obsession with peeling back layers of “reality,” it is the perfect material for director David Fincher. It is the stylistic and thematic cousin of Fincher’s masterpiece Zodiac, and may surpass the 2007 film in reputation. One of the few useful notes I took before surrendering to Fincher’s dark spell was: “Perfect frame after perfect frame.”

Gone Girl is currently teaching me how much of my weekly word count is taken up with summaries. The expertly executed whiplash plot has earned word of mouth that is the envy of Hollywood, and yet recounting it here would be useless. If you’ve read the book, you already know what happens. If you haven’t, you don’t want to know. Here’s the setup: On their fifth wedding anniversary, Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) comes home to find his wife Amy (former Bond girl Rosamund Pike) missing, apparently the victim of a kidnapping. In less than 48 hours, the case becomes a full-blown media circus. Then things get weird.

Gone Girl is about the media. It’s probably the best filmic critique of our industry’s effect on society since Natural Born Killers predicted the metastization of the 24-hour news cycle 20 years ago. It’s marketed as a mystery, but it’s closer to Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole or Sidney Lumet’s Network than a classic mystery like The Big Sleep. Once observed by the media’s electron microscope, the characters behave like a quantum particle forced into choosing a definite state. Is Nick a hero, villain, or victim? Like Schrodinger’s cat suspended between life and death, he exists as all three at once. In a memorable exchange near the end of the film, he confronts his greatest tormentor, talk-show shouter Ellen Abbot (Memphian Missi Pyle), with all of the lies and distortions she has spread about him. “I go where the story is,” she says, even if that means inventing details to support the most lucrative narrative.

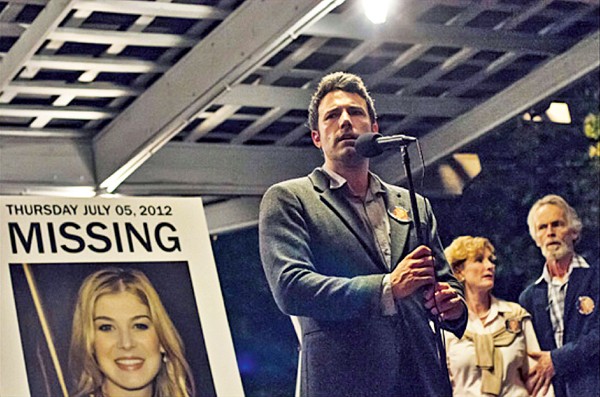

Ben Affleck in Gone Girl

Gone Girl is not misogynistic. Nor is it misandristic. It is misanthropic. Its worldview is so cynical it makes Double Indemnity look like It’s a Wonderful Life. Everyone in the film stoops to their basest level, confirming their sexes’ worst stereotypes. Nick’s glibly charming exterior hides a lazy, emotionally distant philanderer. Amy’s perfect woman exterior hides untold depths of emotional manipulation and cold-blooded lies. As she says, “We’re so cute, I want to punch us.” If, as has been suggested, Fincher’s adaptation tips the moral scales toward the male, it’s because Affleck’s job description as a movie star is: “Be sympathetic on camera.” And Affleck is very good at his job.

Gone Girl is exquisitely well acted. Pike shows complete control over her instrument, shifting into whichever version of Amy the director needs her to be as the points of view change. Kim Dickens shines as Detective Rhonda Boney, the Marge Gunderson-like investigator who proves impotent in the face of overwhelming evil. Neil Patrick Harris manages to take his character Desi Collings from creepy to nice and back again with very limited screen time. But the best of the bunch may be Tyler Perry as the Johnnie Cochran-like defense attorney who cheerfully plots the character assassination of a missing woman who, for all he knows, could be rotting at the bottom of a lake.

Gone Girl is about class. It’s one of the most insightful movies made about the Great Recession, exposing films like Up in the Air as classist dreck. The fear of losing economic status permeates everything. The story’s real inciting incident isn’t Amy’s 2012 disappearance; it’s 2009, when the couple lose their media jobs and are forced to move from New York City to a Missouri McMansion, propped up by debt and illusion. In one telling moment, when one of the movie’s many middle-class Machiavellians finds themselves confronted with actual, desperate lower-class criminals, they are summarily beaten at their own game.

Gone Girl is circular. It’s an appropriate structure for a story where everyone is trapped, either by their sex, their class, their perceptions, or by a whole sick society whose death throes make missing white girls into a growth sector for cable conglomerates.

Gone Girl is a very good movie. You should go see it.