What do a star football player at St. George’s private school, Bartlett Mayor Keith McDonald, State Education Commissioner Kevin Huffman, and former mayor Willie Herenton have in common?

They’re all threats to the future consolidated Memphis and Shelby County public school system, which is going to be riddled with escape hatches that could potentially draw away tens of thousands of students and the state dollars that go with them.

Omar Williams, pictured in The Commercial Appeal today, is a running back at St. George’s who transferred from Manassas High School. He is one of several black athletes who have gone from Memphis public schools to private schools such as St. George’s, Briarcrest, and MUS. The best known include Elliot Williams, who went to St. George’s before playing basketball at Duke and Memphis, and Michael Oher, who went to Briarcrest before starring at Ole Miss and in the NFL. Competitive private schools welcome such student athletes — and some of their non-jock classmates — for reasons of altruism, diversity, and winning championships. Recruiting is not just for colleges. Look at all the University of Memphis basketball players who went to private academies whose specialty is prepping the cream of the crop for careers at Division 1 powerhouse schools and, perhaps, the NBA. I’m surprised Memphis doesn’t have such an “academy” for jocks right here at home already.

Keith McDonald is the most prominent no-ifs-ands-or-buts-about-it proponent of separate suburban school systems. Bartlett, Germantown, Collierville, and Millington are all studying the prospects. That represents a potential loss of tens of thousands of students to the consolidated Shelby County system two years from now.

Charter schools are a third escape hatch. The joint school board this week denied new applications, but the board and MCS Superintendent Kriner Cash seem to have a different point of view than Education Commissioner Huffman. See Jackson Baker’s blog post here.

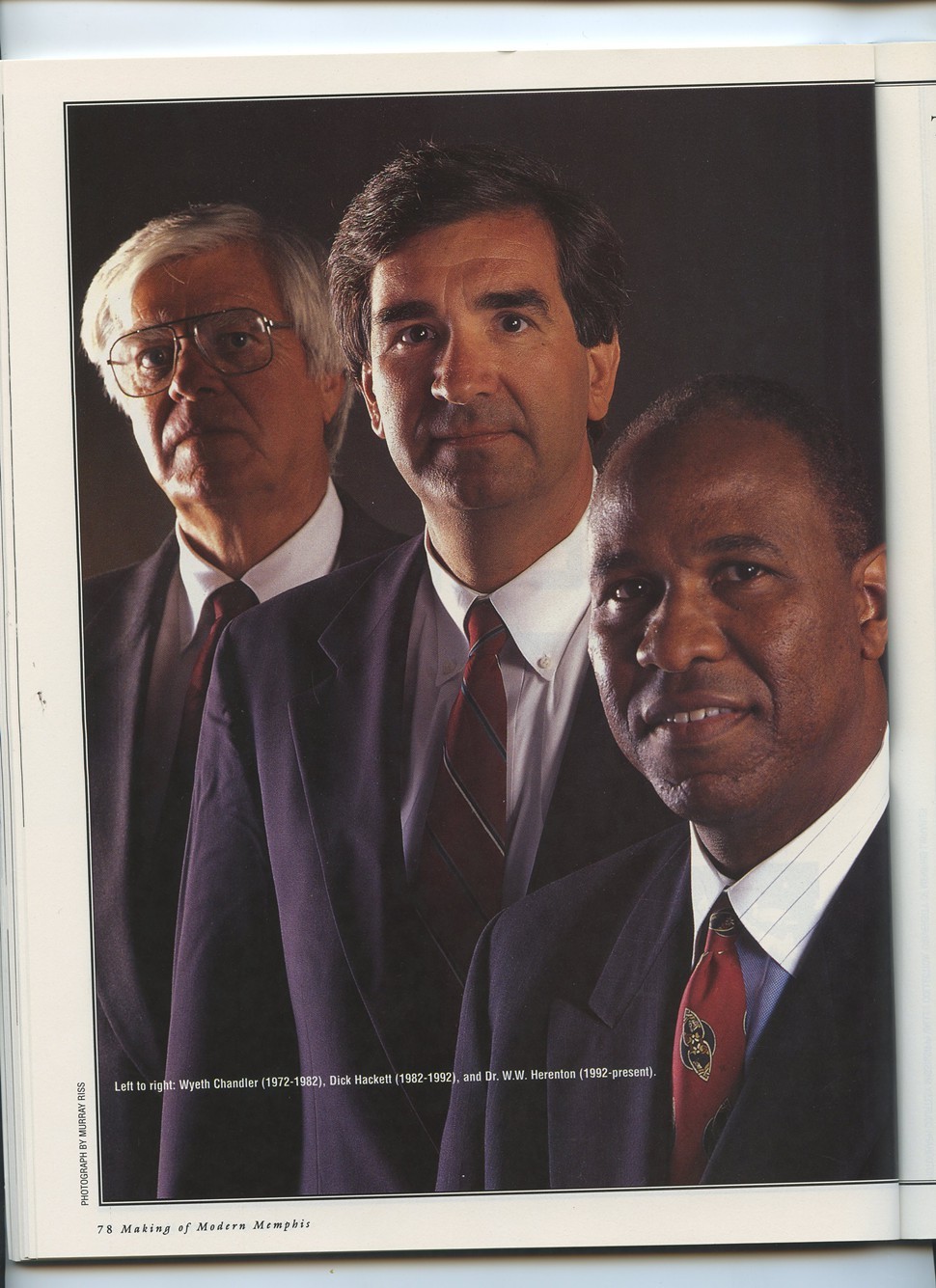

Herenton is one of the applicants for multiple charter schools. He told me Friday he has appealed the denial of his application to the state treasurer’s office, which will look at the impact on finances. A decision is expected in a month. If the treasurer rejects the school board’s claim that charters adversely effect budgets, then Herenton will appeal to the education commissioner, who could direct the school board to approve the application.

“The unified board has not adequately read the future of the Memphis and Shelby county public school system,” Herenton said. “They have not accepted that the educational arena is going to change even more dramatically n the future. MCS has been a colossal failure in terms of educating the children in the inner city and in poverty. Parents, students and teachers deserve the opportunity to participate in a variety of programs.”

Herenton is a former MCS superintendent. Asked what he would do today if he was in Kriner Cash’s shoes, he said “if educators and board members are really concerned about improving academics, then they shouldn’t care who is given leadership. They have to put children first, but they have put their own interests first.”

Cash and board members say they are just trying to operate within their budget, and they have to employ roughly the same number of people and cover the same overhead, at least in the short run, despite the influx and outflow of students.

They’re fighting on multiple fronts. It sometimes looks like a rearguard action because charters have by and large avoided close scrutiny and get pretty good press in Memphis and Nashville.

But setting up a new school much less a new system is hard and expensive. Sooner or later, MCS/SCS will have to stop playing defense and go on offense — in other words, make the positive case for a big unified school system with veteran teachers, principals, coaches, marching bands, extracurricular activities, no tuition, proud tradition, bus routes, neighborhood identity, stability, whatever. The appeal will have to be “why you should choose us” not “why you should not be allowed to leave us.”

Once deregulation begins, there is no stopping it. There is a very good chance that the future consolidated system could become the current MCS system, minus hundreds if not thousands of its most athletic, college-bound, and motivated students and parents. That’s the thing about escape hatches.