Well, the weather outside is, if not exactly frightful, certainly shading toward cold, blustery, and gray. Time-tested local pastimes like porch drinkin’ and riverside running are getting a little less comfortable. The good news? Books exist, and Memphians, from Shelby Foote to Katori Hall, have a certifiable knack for storytelling.

Not to go all LeVar Burton’s Reading Rainbow on you, but a book really is the least expensive ticket to another world, a new perspective. In this issue, we’ve turned the page on eight new books by Bluff City authors. They each represent a chance to visit a new place, be it the Memphis music scene of yesteryear, the British Isles in World War II, a fictional dystopian future, or the life and times of a real rock-and-roll legend (a moral giant, if you will). So, whether you’re in search of a gift for the bookworm in your family or a cold-weather social-distancing activity for yourself, we’ve got you covered. Trust me; I’ve been social distancing since Scholastic Book Fair, 1992. Read on. — Jesse Davis

I Die Each Time I Hear the Sound

by Mike Doughty

Hachette Books, $17.99

I now know exactly what not to say to Mike Doughty, thanks to his new book.

I’ve seen him around. You probably have, too. He’s lived in Memphis now for a few years. I’ll see him occasionally at Fresh Market, and we stood in the same line to vote this year. I love his music, but it’s distasteful to brace a guy when he’s picking produce or a president.

In I Die Each Time I Hear the Sound, Doughty describes the unique unpleasantness of fans telling him how they discovered his old band, Soul Coughing. Many of those stories basically boil down to “my roommate had the CD.” Duly noted.

It’s an honest insight into a particular moment, unique to an internationally known musician who makes unique music that appeals to a unique audience. The book is filled with these distinctive insights, delivered with a lot of warmth and humor. But Doughty’s also nakedly honest about anxiety, depression, and shame. The mix of these gives I Die Each Time I Hear the Sound a fresh, broad appeal. It’s a rock-and-roll book about a real person.

For example: How would you feel if David Letterman complimented your guitar — not your music — on national television? What if you responded with snark and he walked away? What if you found out later that Letterman compliments a lot of people’s guitars on the show and was trying to be personable?

The book is filled with honest stories from the road, talking to Little Richard in a Los Angeles elevator, eating McDonald’s in Tokyo, meeting a drunken Evan Dando at Glastonbury, and arguing/not arguing with his estranged band over the liner notes of a compilation album.

But the book is most brilliant when Doughty describes music, drawing an incredibly accurate atlas of the sounds as he hears them.

Here’s how he describes Steven Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians on a drive through Washington State: “It was like those undulant marimbas rose from the yellow hills. The melodies change as if you’re passing them: a note materializes at the end, a note on the top disappears.”

Here’s Doughty on “These Arms of Mine”: “When Otis Redding sang the word mine — the second repetition, when the note gets higher — the word mine becomes a glowing flower, which expanded into the sky, then the sky opened into the cosmos beyond the cosmos.” — Toby Sells

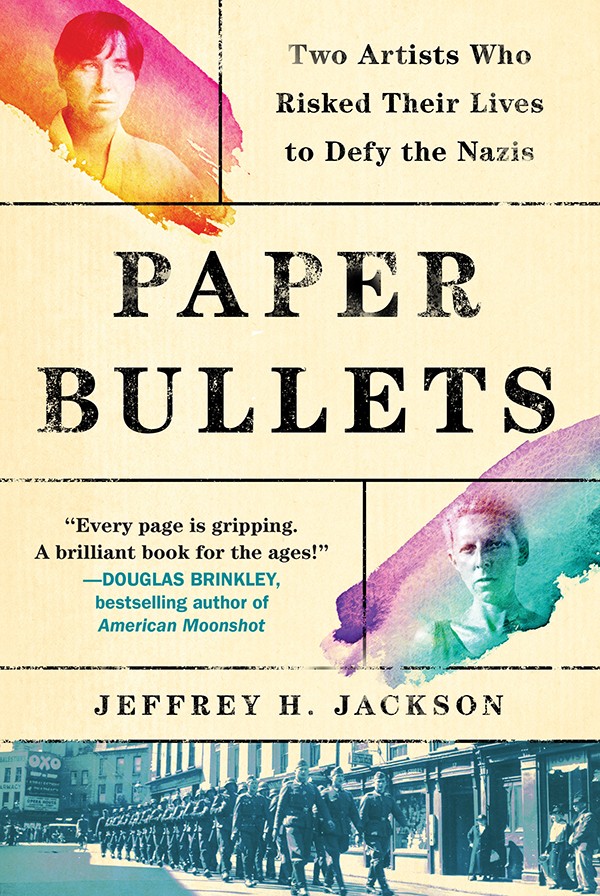

Paper Bullets

by Jeffrey H. Jackson

Algonquin Books, $27.95

Rhodes professor Jeffrey H. Jackson couldn’t have known how timely a subject he picked when he began his research into French artists and romantic partners Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe for the book that would become Paper Bullets. Resistance, the key motif of Jackson’s just-released (and already lauded — Paper Bullets has been longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Non-Fiction) tome, has become something of the watchword of the contemporary era, certainly of the last four years, making Jackson’s telling of two lesbian artists who put all their considerable talents to use to resist the Nazi occupation of the English Channel island of Jersey a story well-suited to the cultural moment.

Known in the art world as Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Lucy and Suzanne operated a covert campaign to demoralize the German occupying army, striking at their psyche with their “paper bullets” — notes hidden in magazines and surreptitiously slipped into pockets, photo collages, poems, anything that might make the invaders doubt the morality of their position.

Before their resistance in Jersey, their relationship made Lucy and Suzanne outlaws, of a sort. “Their relationship was not their only secret,” Jackson writes in Paper Bullets. “According to Jewish tradition, Lucy would not have been considered Jewish because her mother was not a Jew. However, Nazi racial law made no such distinction.”

In Paris, before the war, surrounded by artists and entrepreneurs who were anything but stereotypical and enmeshed in radical politics, Lucy and Suzanne were at the cutting edge of a convention-defying moment in art history, in a Paris still reeling from the heavy losses sustained in the first World War. It was the perfect training ground.

As women working in a male-driven field, as women who loved each other, Lucy and Suzanne had practice viewing the world from a different perspective — and often having to fight for their right to participate. Lucy, too, suffered from chronic illnesses that set her apart from many of her fellows. Their status as unconventional artists working with Dadaists and Surrealists taught them the power of art as a way to subvert expectations.

The bulk of the action in Paper Bullets takes place on the island of Jersey, as Suzanne and Lucy begin to fight back against the occupation, steadily employing more sophisticated methods in their two-woman PSYOPS campaign. This is no dry history; rather, Paper Bullets almost hums with the tension of a tightly plotted thriller. Jackson deftly balances the narrative, though, giving the reader a taste of the romance that fueled the resistors’ relationship, the art scene that honed their skills, and the war that compelled them to find a way to fight. Paper Bullets has it all — it’s a tale of romance in spite of the odds, a slice of art history, and an inspirational World War II story. It is, simply put, nearly impossible to put down. — JD

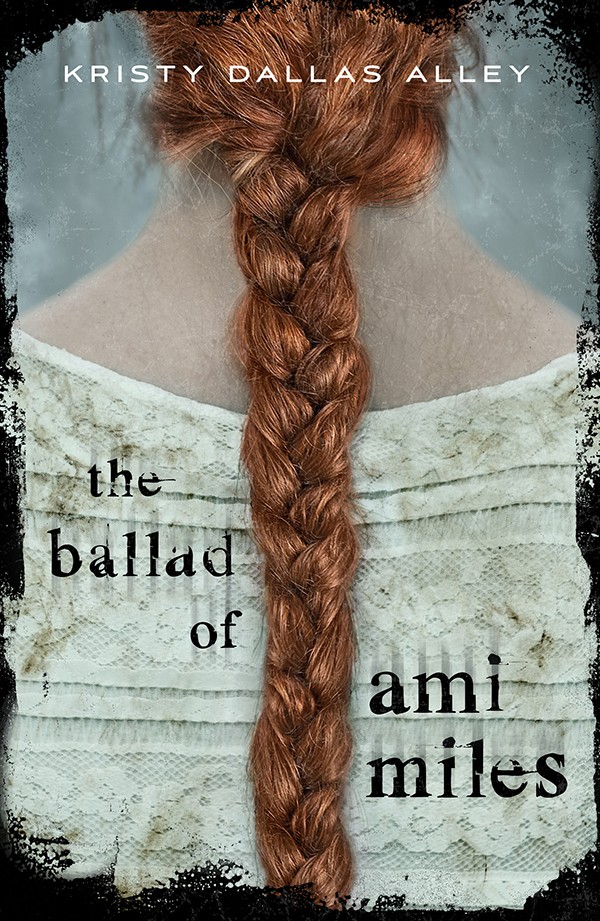

The Ballad of Ami Miles

by Kristy Dallas Alley

Macmillan Books, $17.99

The more things change, the more they stay the same. While the world as we know it is broken in Kristy Dallas Alley’s debut novel, The Ballad of Ami Miles, many issues that plague our current society are all too rampant. Sixteen-year-old heroine Ami Miles has grown up in relative safety at her family’s survival compound, but when she receives a clue about her long-vanished mother’s whereabouts, she sets out to learn more about herself, and the world outside the compound.

Ami grows up at Heavenly Shepherd, a survival compound run by her grandfather, Solomon Miles. The America she knows has drifted into a post-apocalyptic collection of small communities after a virus rendered most of the population infertile. Any woman who does have the ability to bear children is quickly gobbled up by government “C-PAF” agents.

That fear prompted Ami’s mother to flee when she was a child, leaving her daughter to fend for herself in Solomon’s controlling environment. And her grandfather, the worst kind of bigoted evangelical, sees Ami as nothing more than a vessel to continue on the Miles lineage. When he invites a man to the compound to impregnate Ami, all bets are off. Her aunt provides her with directions to her mom’s last known location and sends Ami on her way with supplies.

While Ami Miles might have the YA label, Alley doesn’t treat her readers with kid gloves. A post-apocalyptic America doesn’t mean societal issues have gone away, and Ami tackles racism, homophobia, and plenty of other prevalent social issues for the first time after escaping Heavenly Shepherd. And it’s not all smooth sailing for the good-natured protagonist; Alley expertly weaves in a constant thread of deprogramming along Ami’s journey. Having basically grown up in a cult, it’s hard for Ami to jettison the thoughts and “values” that have been pounded into her since day one. Even as she learns more about the world, even as she makes new friends, and even as another young woman catches her eye, her grandfather’s directive to find a man and make a baby sits uncomfortably in the back of her mind.

The Ballad of Ami Miles is an ode to many things: self-growth, finding new experiences, welcoming in ideas that aren’t your own. Every step of her journey, Ami is up for the tough challenges that lay in her path. Reading from 2020’s perspective, where so many are insulated in their thought bubbles by algorithms, social media, and the like, Ami Miles is the perfect tonic. With a brave face, there’s always room for growth and new experiences.

I’m not sure I’m the target demographic for The Ballad of Ami Miles, but Alley’s electric pacing kept me hooked until the last page; ultimately, I blazed through in just two sittings. Through Ami, Alley never puts a foot wrong while crafting her narrative. Hard to believe this is a debut. — Samuel X. Cicci

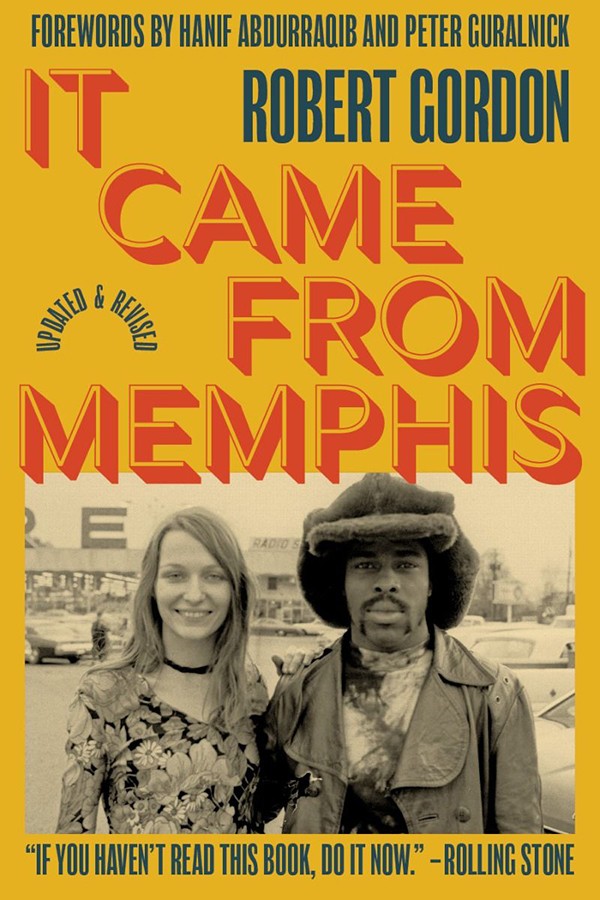

It Came From Memphis

by Robert Gordon

Third Man Books, $19.95

Robert Gordon’s 1995 opus, It Came From Memphis, quietly but quickly grew into a cult classic, a must-read for any music aficionado wanting learn about the gritty, Black and white roots of rock-and-roll in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s — and the city where they were planted. Gordon’s cast of characters was as wild and eccentric as the river town that made them: Dewey Phillips, Sputnik Monroe, Sam Phillips, Furry Lewis, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, Bill Eggleston, Booker T., Tav Falco. Not to mention a supporting cast of midget wrestlers, motorcycle gangs, and all-around weirdos.

Iconic Memphis musician and Zelig-like guru Jim Dickinson knew many of the characters and their backstories, and he is a primal force in ICFM. His insights, along with Gordon’s extensive research, many invaluable interviews, and avid storytelling, give the book its authentic juice, chapter after chapter. There are plentiful you-are-there tales from the city’s iconic music studios — Stax, Ardent, Sun. There are long nights, inspired bouts of musical brilliance, booze and blunts and pills, bizarre escapades, and more than a little madness.

Now there’s a new 25th anniversary edition of It Came From Memphis, published by Jack White’s Third Man Books (the imprint that earlier this year published Memphian Sheree Renée Thomas’ Nine Bar Blues). And better yet, it’s not just a reprint. Much has been added: all-new photos, updated stories and interviews, and fresh opinions and perspectives from Gordon and others, including Peter Guralnick.

The original classic book is still there. It’s just been enhanced — and beautifully so. As Gordon admits in his preface, the original was something of “a guy book,” so he has brought more women’s voices and influences into this version. It’s a seamless and welcome addition.

As the cover blurb notes: “Vienna in the 1880s. Paris in the 1920s. Memphis in the 1950s. These are the paradigm shifts of modern culture. … Memphis embraced black culture when dominant society ignored or abhorred it. The effect rocked the world.”

That it did. It Came From Memphis is essential reading for anyone who wants to deepen their understanding of this city and its musical history. — Bruce VanWyngarden

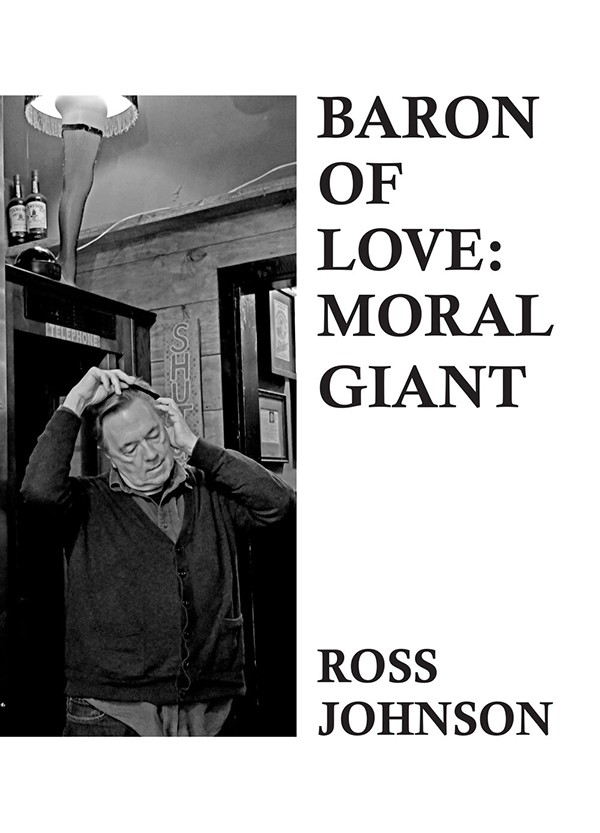

Baron of Love: Moral Giant

by Ross Johnson

Spacecase Records, $15

Like the author himself (a friend and erstwhile bandmate of mine), this slim memoir (published by Spacecase Records) is a pulsating mass of contradictions that somehow self-assemble into a sentient whole. As such, it captures the way most of us live in fits and starts, and with good humor; but in Ross’ case, the fits and starts happened between the buccaneering world of rock-and-roll and the library shelves, first landing you backstage with Iggy Pop and the New York Dolls, then sending you “collapsing into a spiral of self-contempt and regret.”

The common thread is Ross’ keen eye, sharpened from an early age. With echoes of his father, a journalist in Little Rock, this book is bursting with vivid, keenly observed moments. The memories unfold in a chaotic jumble of brief vignettes, so the evocative tales of rock writing and rock drumming, with which the author made his name and honed his taste, rub shoulders uneasily with snapshots (both literal and figurative) of Ross’ youth and the dramas of adulthood. All are rendered in the clean prose of a reporter turning his investigative eye inward as well as outward. And some turns of phrase, be it “toilet club” or “mental patient rock,” are sheer poetry.

Without prejudice, Ross objectively notes the brazen racism of his Arkansas childhood, his ex-girlfriend’s career as a groupie, the fascistic roots of Alcoholics Anonymous, and the size of Iggy Pop’s schlong. Every chapter title might be a line from “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,” as our hero rattles off the wonders and horrors he’s seen: “Who’s Alex Chilton?,” “Roland Janes,” “Creem Magazine Saved My Life,” “Swerve Into Perv,” “Charlie Feathers,” “The Klitz,” “Guiltabilly.” Through it all, his time with the Panther Burns, the band he co-founded with Chilton and Tav Falco, weaves in and out of the narrative like a tipsy driver you just can’t shake.

And “Baron of Love,” the inspired song/seance he cut with Chilton in 1978, hangs over the highway like a harvest moon.

What saves the book from being mere barstool boasting is Ross’ reflective instinct. Dollops of cultural studies and politics inform his musings on the ethics of the sexism, racism, and rockism at play in every scene. It may be more of a moral microscope, but if this be gossip, it’s gossip with a heart, and gossip with a brain. — Alex Greene

LGBTQ+ Revolution 2.0

by Jill Fredenburg

New Degree Press, $16.99

With the craziness and hopelessness some have felt in the last four years, it can be easy to forget how far we have come as a country in terms of social issues. In just 50 years, we have gone from segregating people based on the color of their skin to allowing true freedom of marriage. Reflecting on this can be astounding.

Jill Fredenburg’s LGBTQ+ Revolution 2.0, to me, is a product of the successes that we have made as a country in recent years. The book, which is structured as a collection of narratives sharing experiences and stories from people on different spots of the LGBTQ+ spectrum, tells the struggles, triumphs, and day-to-day lives of those who are in the LGBTQ+ community. Over 21 chapters, Fredenburg discusses all permutations of the LGBTQ community.

It’s not an easy read. At times I found myself angry and frustrated by the injustices faced by those that Fredenburg wrote about. Other times I felt hopeless to help. Fredenburg creates a connection between the reader and those featured in the book so that you can truly understand their lives, and the effect is immediate and intense. For all the sad stories and times of struggle there are also stories of triumph. But in that work Fredenburg also finds hope and strength in the knowledge that the LGBTQ movement is stronger than ever.

“I started writing this book with the hope that the process would help me understand how experiences like Cassandra’s and my own fit into the larger movement surrounding LGBTQ+ identity,” Fredenburg writes in her introduction. “What I discovered has made me excited for the next wave of LGBTQ+ rights.”

Fredenburg’s book LGBTQ+ Revolution 2.0 is not an easy read, but it’s a needed one. She speaks for the silent other who is often ignored and left out of the conversation, showing the good and the bad, then inviting others into the conversation. Her work is important reading for everyone, and she ends her book with a reminder that I think all people can live and learn by: “Who will you be, who and how will you love, without shame?” — Matthew J. Harris

Emergence

by Shira Shiloah

Salty Air Publishing, $15.99

Dr. Shira Shiloah is a local anesthesiologist who decided she’d get into the world of writing medical thrillers. Her debut novel is Emergence, set in Memphis and with ample description of familiar sights in and around Downtown. Shiloah also gives us a strong female anesthesiologist (beautiful, highly competent, owns a dog, touched by personal tragedy), a suitably wicked surgeon (an arrogant platinum blonde, owns no dogs, coked-up misogynist), and a sensitive resident doctor (thoughtful, supportive, easy on the eyes, owns a dog).

And there is plenty of lab-coat-ripping romance slathered throughout like a medical grade lubricant. In fact, Emergence rocks back and forth between incisions and intercourse, blending romance and thriller genres.

Allow these excerpts to speak for themselves:

“She could make out the silhouette of his muscular torso. His jeans were as loose as his smile. There were no blood or drapes between them tonight, just clear skin and healthy hormones. His gaze took her in.”

And: “He took the knife and expertly sliced him at the level of the jugular vein. The man screamed and struggled to get away, but with one sweep of his hand D.K. stabbed his cricoid, his voice box, so he’d be silent.”

If those passages appeal to you, then it must be just what the doctor ordered. — Jon W. Sparks

Memphis Mayhem

by David A. Less

ECW Press, $16.95

If the title Memphis Mayhem sounds like it could be describing either a crime wave or a chip-on-the-shoulder attitude or an era of public turbulence, the new book by Memphis music historian David Less concerns all of those things, but mainly it is history and memoir of the various strains of music that have percolated out of Memphis and defined the river city in its seminal relationship with the outer world.

As the author himself, a writer and archivist and third-generation Memphian, describes his work, “It is a story of a city and a culture and fosters independent thinking in the midst of a strict, conservative society. There is a spirit of self reliance in Memphis. It is born of the poverty and oppression shared by Blacks and whites here, who have nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

Parts of Less’ narrative are familiar from other sources, but Less does not content himself with a roster of luminaries and a catalogue of styles. His treatment of Memphis’ early blues masters, for example, is against a backdrop of the gambling, desperate chance-taking, and crazy optimism that characterized Beale Street and its antecedent neighborhoods. He tells his tale in an episodic style that at first seems somewhat disjointed but is more accurately revealed to be the mosaic that it is.

Almost in the manner of a jig-saw puzzle, the pieces ultimately fit together — Yellow Fever; the band rivalry between two Black high schools, Manassas and Booker T. Washington, and the dispersing into the world of the innovative results; the laboratory of Black and white music sources that was Sam Phillips’ Sun Studio; and the serendipity of a second commercial-music wave stemming as much from the self-seeking curiosity of white Messick High students like Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn as anything else.

Less explains why it is that Memphis music tends to be “behind the beat,” and he notes the importance of landmarks — like West Memphis’ Plantation Inn, where white Memphis high-schoolers learned their musical ABCs from innovative Black performers, and the Lorraine Motel, important as a honing place for white and Black musicians before it became a site of infamy and a shrine to the great MLK.

It’s all here — the jazz masters of the Crump-ordered “clean-up” period, Daddy-O Dewey, Ardent Studios, Chips Moman, Willie Mitchell, Al Green. And all of it pegged to the hard-boiled but generous local populations that lived in ever-treacherous and sometimes ominous times. (It is surely no accident, by the way, that much of the narrative of Less’ book derives from interviews with veterans of the Memphis music wars now living in the plusher confines of Nashville, which has a kind of finishing-school or retirement-home relationship to the dangerous but lively city on the Mississippi.) — Jackson Baker