Matthew Hasty did not get his art degree from the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College in Sarasota, Florida. He got a bachelor’s in fine arts from the Ringling College of Art and Design, which, coincidentally, is also in Sarasota.

When he tells people where he went to art school, Hasty says, “People think it’s a clown school.”

And, he adds, “I probably would have done better as a clown. I think clowns make more money.”

Despite the geographical and Ringling connection, Hasty doesn’t include any clowns in his painting repertoire. His works, which are reminiscent of 19th-century Hudson River landscapes, are more likely to linger on vivid sunsets and images of the Mississippi River. But he has also worked on Elvis-themed paintings, including one of Graceland’s Jungle Room, as well as Sun Studio and scenes from his European travels.

Commenting on Hasty’s work, noted artist Dolph Smith says, “I don’t just view them with pleasure and profound admiration. I always wish I was there. I don’t stand in front of them. I enter them. I actually feel them.”

His work has graced the official RiverArtsFest posters and is included in collections at Germantown Performing Arts Center, International Paper Company, Methodist Shorb Tower at Methodist University Hospital, and others.

Hasty is exhibiting 19 of his paintings in his show, “The Illusion of Permanence,” which runs through November 20th at L Ross Gallery.

Workshopping

A native Memphian, Hasty chose Ringling over other schools, including Memphis College of Art, when he was 19. The choice was based on a simple equation. “There was a beach in Sarasota,” he says. “There was an art school.”

He originally studied graphic design at Ringling, but, he says,“I would have gone crazy trying to do graphic design. It’s too disciplined, I think, at the heart of it. You’re basically trying to please a client all the time. Which is still kind of what you do, I guess.

“Looking back, I wanted more of an atelier education, how they would have taught you in France. It’s just a workshop. The word means ‘workshop.’ It’s more of a rigorous training where they teach you how to use the materials.”

According to Hasty, an atelier education is the opposite of being “thrown into a classroom” where a teacher will say, “Just go outside, make a landscape, come back, and we’ll do a critique.” The Memphis-based artist says that method is “not teaching anybody anything.”

Hasty moved to New York after he graduated. “I wanted to get into Leo Castelli’s gallery, but that was ambitious. It was the most famous gallery, to me, at the time.”

Instead of getting his work in the gallery that represented artists Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and other notables, Hasty became a house painter. “At least I didn’t have to get different clothes. I didn’t have to wear a tie.”

Finding a Palette

Hasty was still searching for his voice, his own particular style, but most of his work took the form of realism. “I did a lot of figurative work. I loved the Flemish masters like Jan van Eyck,” he says. Rembrandt was one of Hasty’s favorite painters “of all time.” A portrait of a stranger can be something boring to look at, but not when Rembrandt painted it, Hasty says. “The way he handled paint was so luscious. You can just get lost in somebody’s nose.”

Or, Hasty continues, enraptured, “just a shadow of someone’s lace collar. They’re just magnificent.”

During that time, Hasty experimented with a subject that has occupied artists since the dawn of time. He painted “a lot of religious, kind of allegorical things, but still kind of angry.” He did a dark painting of Adam and Eve. Adam is eating an apple that’s “glowing, radioactive,” Hasty says. “Nobody wanted that. A relative of mine said, ‘Why don’t you paint things people want to look at?’ So, I reflected on that and I was like, ‘Maybe you’re right.’”

He landed a show at the old The Wall Street Gallery in Huntington, Long Island. His pieces, which included a whimsical, dreamlike painting of a man getting shot out of a cannon at a circus, “were a little less angry” than some of his other work.

Hasty sold a handful of paintings during that time. “The guy I worked for, the house painter, my boss, bought a few paintings.”

Moon Over Memphis

In his late twenties, Hasty moved back to Memphis. He worked on some murals and did some gilding and column marbleizing for one of the Wonders: The Memphis International Culture Series exhibits. But, he admits, “I didn’t have any kind of real plan.”

Hasty was commissioned to do murals for people’s homes. He also did a lot of interior painting of crown moulding and gilding for designers William R. Eubanks and Warner Moore. They helped him get his artwork placed in some of the homes they were working on, Hasty says.

He began showing his paintings with artist David Mah at Mah’s studio. “I would paint rice fields. And the river has been a long-term subject, and cotton fields. I still paint cotton fields.”

Sometimes he’ll say, “If I see one more cotton field … ” but before finishing that sentence, he adds, “It’s keeping the lights on. People love it.”

He did a lot of Mississippi River paintings for people who live on the bluffs. And he painted landscapes for hunters. “Hunters will say, ‘Come paint my hunting holes.’”

The hunting paintings were popular with women as well as men. “Women like it ’cause it looks pretty and guys like it because it looks like where they go hunting. So, I feel like I’m checking two people’s boxes.”

The moon is one of Hasty’s favorite subjects. “Like the blue moon we had the other night. The moon is so arresting to see when it’s full. It always inspires me to make another one. I’ve painted this moon quite a lot. I’ve painted the moon over Italy, France.”

He did a painting of Sun Studio at night “with the eclipsed moon above Sun Studio.”

“People are inundated with images all day with TV. Images are coming at you from every angle — your phone, your iPad. You can scroll and look at your phone all day. I try to make things that calm you down or make you feel serene.”

Hasty, who has only done “a handful of portraits,” says, “Why would I try to get in that world when there are people doing those paintings far and away better than I could do?”

He’d like to do some work that incorporates physics. “To do a piece that’s connected to the quantum world of particles, but utilizing painting. Two dimensional or three dimensional pieces. I can do everything I know how to do. Drawing, oil painting, or gilding, or sculpture, wood carving — incorporate all that into a body of work that has something to do with physics.”

The Illusion of Permanence

Hasty’s show at L Ross Gallery includes his landscapes, sunsets, and river scenes. Explaining the show’s title, “The Illusion of Permanence,” Hasty says, “It’s a different way of saying change is the only thing that’s constant. Even these paintings that capture a sunset. At some point they’re just going to be dust in the wind.”

Also at the gallery are prints of Hasty’s RiverArtsFest posters for 2020, which never took place because of the pandemic, and the recent 2021 event.

Describing Memphis Rising, the 2021 poster, Hasty says, “I’ve never painted the Hernando DeSoto Bridge. When the bridge got broken and nobody could use it, you realized what an important structure that is for just this area. The country, almost. It sort of crippled this region to not have that bridge working.”

The Gloaming is the title of the 2020 poster. “A hazy sunset over the river.”

The 2020 painting is the “sun going down on 2020,” Hasty says. The 2021 poster, on the other hand, depicts its subject on the upswing, with “the moon rising over Memphis. We’re growing and this town is becoming more significant.”

L Ross Gallery owner Laurie Brown says, “In addition to the beauty and technical skill of Matthew’s paintings, such that one feels they could just walk into the landscape, his work also deeply connects viewers with their past. It’s a privilege to hear the stories of fondly remembered grandparents, vacation travels … that visitors to the gallery share with me.”

Voyage of Life: Childhood

Hasty began painting when he was in diapers, but his medium was a bit unconventional.

According to his father, Hasty painted on the wall near his crib. “I painted with my poop, basically,” Hasty says.

And, he says, “My dad tells the story, but I think he intends for it to embarrass me. But now I have embraced it as my first artistic outlet. To use that medium on the wall outside my crib.”

Hasty drew a lot as a child. “Oil paint, markers, and charcoal and watercolors, just the gambit of art supplies.”

He did figurative work growing up. “I found a piece recently in a book my mom had. I must have been 10. I got into Queen and, apparently, drawing them on stage with guys playing guitar. People are a centimeter tall.”

But, he says, “It doesn’t show any real promise. There’s no indication I might be good at art. It’s very childlike. Like a 10-year-old did it.” Which, of course, is the case.

His mother was an artist, Hasty says. “My mom had zillions of books and there was art all over the house.” He describes her paintings as “weird, surreal work. It wasn’t sellable.”

His mother, who was never able to be serious about her art, had to “get a real job,” so she worked as a cosmetic buyer for the old McRae’s department store. They moved a lot because of her job, so Hasty lived in Fort Worth, Dallas, and other places.

His artwork in his twenties was similar to his mother’s. “Lots of death, angst-filled paintings that were almost like a heavy metal album cover. A friend of mine used to call it ‘zombie porn.’”

Sunset on a River

The artist has come a long way from centimeter-tall rock stars and faux heavy metal album art; Hasty now sells his work all over the country. The late John Prine owned one of his paintings, Hasty says. “It’s a landscape. I think it’s a sunset on a river. Not a huge one.”

The wife of the late singer-songwriter bought the painting at a gallery in Nashville, says Hasty, who later met Prine. “I got to meet him backstage at the Ryman. He wanted to meet me, which is so far out. I could have died after that. I play his songs all the time.”

Prine was excited to meet him, Hasty says. “His wife said, ‘This is Matthew.’ He kind of perked up and lunged at me, shaking my hand. He’s one of my heroes. He said, ‘I wake up every day and see your painting.’ I was like, ‘Please write a song about it.’ I mean, just the fact that John Prine woke up every day and saw my painting filled me with just the biggest joy in life.”

When he’s not painting or meeting his heroes backstage at the Ryman, Hasty enjoys traveling to Europe. “I’ve been working on these little panels and painting places I’ve traveled recently: France, Spain, Italy, Cuba.

“I started bawling at The Raft of the Medusa by Theodore Gericault in the Louvre. I used to see it in the books. Just epic.”

He loves to paint works by Rembrandt. He’s tried to paint Rembrandt’s self-portraits “half a dozen times just to see if I could do it. Like a violinist tries to play a Paganini piece.”

Hasty now works out of his studio at Marshall Arts. “Somehow, I’ve been able to keep myself alive just by making paintings. I think I was just trying to make my mom proud of me. Which I think she was.”

His mother died three years ago. “She got breast cancer, but it came back in her spine. I still feel like she’s with me. I talk to my mom so much. I feel like she’s my Obi-Wan Kenobi. I think she communicates with me still.

“I always felt terrible my mom didn’t follow her dream. Knowing that kind of pushed me as an artist. I think that was my mom’s intent.”

L Ross Gallery is at 5040 Sanderlin Avenue, No. 103; (901) 767-2200.

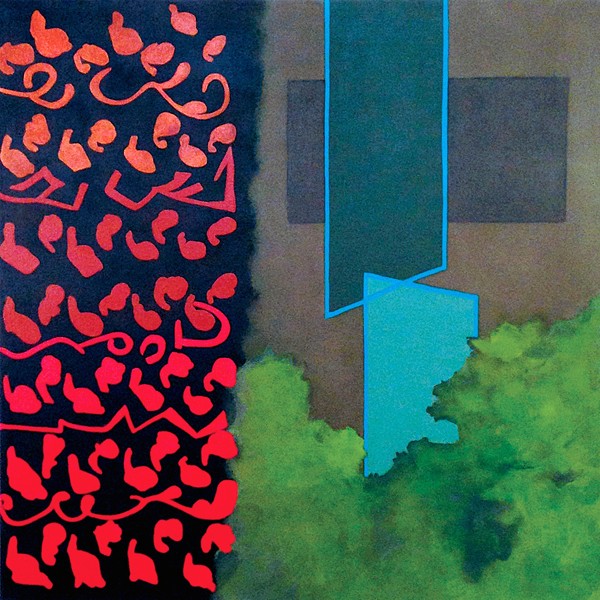

Fletcher Golden

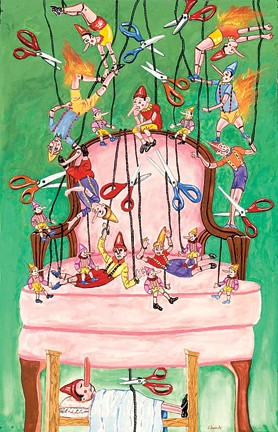

Fletcher Golden  Jeanne Seagle

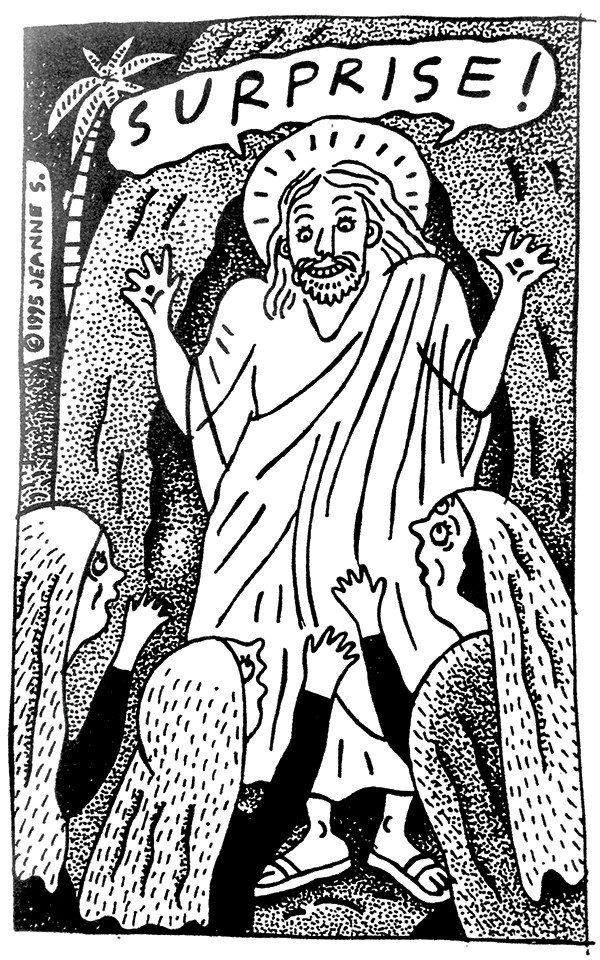

Jeanne Seagle  Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle  Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle  Jeanne Seagle

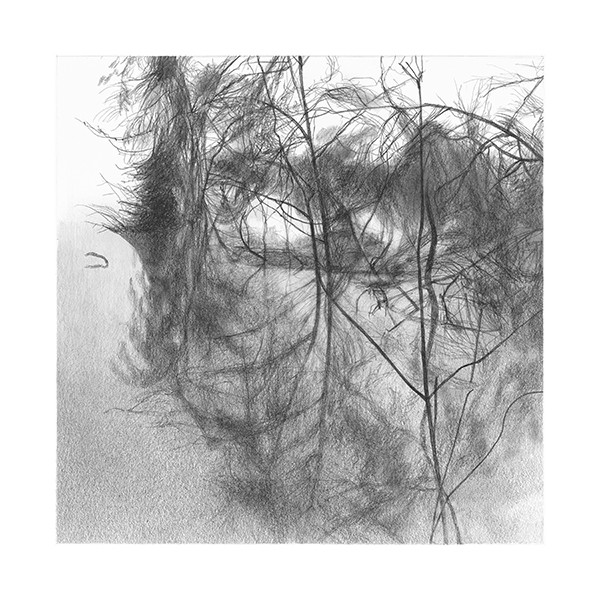

Jeanne Seagle  Courtesy of Alden Weatherbie

Courtesy of Alden Weatherbie  Colored doodle courtesy of Alden Weatherbie

Colored doodle courtesy of Alden Weatherbie