In late March 2019, something remarkable happened in the United States Senate. As the news cycle was consumed with Attorney General William Barr’s maneuvering to suppress the Mueller report, Senator Lamar Alexander, the senior member of Tennessee’s congressional delegation, rose to speak. “I believe climate change is real,” the senator said. “I believe humans are a major part of causing it. And we ought to do something about it.”

For the vast majority of humanity, Alexander’s opening statement is conventional wisdom, but coming from a 78-year-old, lifelong Republican, it sounded like heresy. Virtually alone among all political parties on planet Earth, the GOP has made denying climate change the core of its political identity. Republican President Donald Trump called climate change “a Chinese hoax.”

So why was Alexander, who the League of Conservation Voters says has voted against environmental bills 80 percent of the time during his three terms in the Senate, suddenly changing his tune?

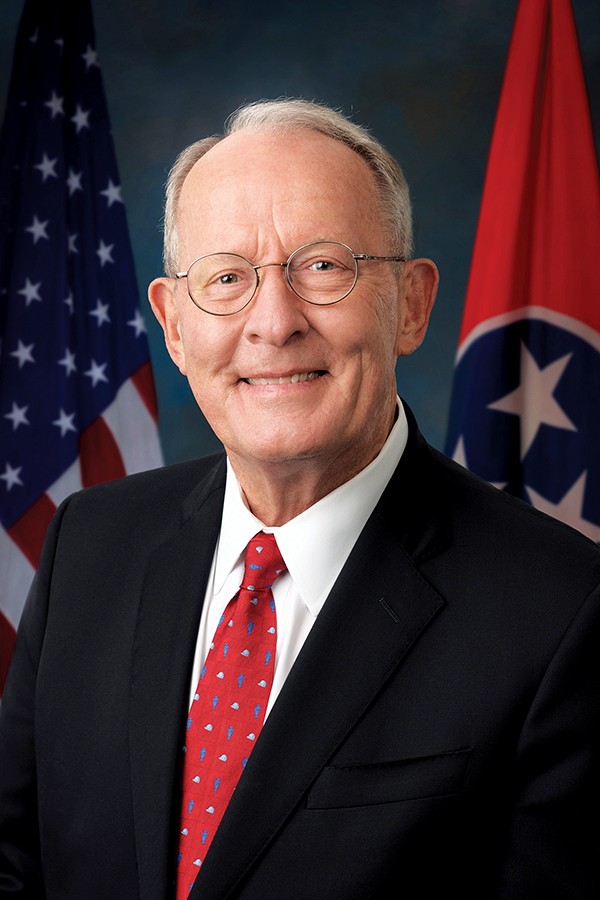

Senator Lamar Alexander

The answer is the Green New Deal, a proposal by Massachusetts Democratic Senator Edward J. Markey and New York Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that would mandate sweeping action to curb greenhouse gas emissions and transform American life. “It’s the national-security, economic, health-care, and moral issue of our time,” said Markey at a Washington press conference on March 26th.

Two weeks earlier, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer had called out Republican senators. Speaking to The Hill, he said “We are going to ask our Republican colleagues three simple questions: One, is climate change real? Two, is it caused by human activity? And three, should Congress do something about it?”

Two Degrees of Warming

The occasion of Alexander’s battlefield conversion was a show vote, called by Republican Speaker Mitch McConnell, without the requisite committee hearings, on the Green New Deal proposal. The resolution was defeated 57-0, with all but three Democratic Senators voting “present” in protest. But the fact that McConnell thought it necessary to even hold a show vote in the first place indicates that the “party of no” on climate change is feeling unprecedented pressure.

Survey after survey indicates that the fossil-fuel-industry-sponsored denialist position is crumbling, and that voters want action on climate change. A December 2018 poll conducted jointly by Yale and George Mason University’s Climate Communications programs revealed that 59 percent of respondents were either “alarmed” or “concerned” about climate change — a 16 percent jump in five years. The number of respondents who were “dismissive” or “doubtful” fell 10 points during that same period. Gallup, who has been tracking attitudes toward the issue since 2001, says that 66 percent of respondents believe global warming is caused by human activity, an increase of 11 points since 2015.

The scientific consensus on the reality of climate change has changed little since 1988, when NASA scientist James Hanson told Congress “The greenhouse effect has been detected and is changing our climate now.”

In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its latest report, which began, “Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C would require rapid, far-reaching, and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.”

That 1.5 degrees of warming is now inevitable, given the amount of greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere. Severe weather events are and will continue to become more frequent and more severe. Sea levels will rise, threatening to inundate cities such as Miami and New Orleans.

The difference in a world that has warmed an average of 1.5 degrees C and one that has warmed 2.0 degrees C over pre-industrial levels may not sound like much, but it is, says the IPCC. “For instance, by 2100, global sea level rise would be 10 cm lower with global warming of 1.5 C compared with 2.0 C. The likelihood of an Arctic Ocean free of sea ice in summer would be once per century with global warming of 1.5 C, compared with at least once per decade with 2.0 C. Coral reefs would decline by 70 to 90 percent with global warming of 1.5 C, whereas virtually all (>99 percent) would be lost with 2.0 C.”

But there’s another reason climate scientists have made avoiding a rise to 2.0 C of warming their target. After that point, the climate models that scientists have spent decades refining and collecting data for break down. We just don’t know what will happen beyond 2.0 C, except that it won’t look like any Earth humans have ever seen.

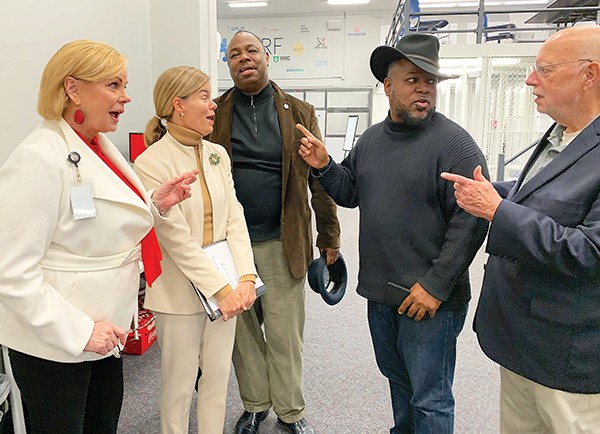

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Duffy-Marie Arnoult (left) and Vance LaVelle are officially tree huggers.

The Climate Reality Project

“The environment has always been important to me,” Duffy-Marie Arnoult says. “I planted a tree in the fourth grade, and now that tree is the only tree standing over the family house in Midtown. That storm that came through two years ago in May just devastated the neighborhood.”

Arnoult left Memphis to attend Notre Dame University. After working as a photographer for Getty Images and other agencies in New York, she decided to pursue a certification in Sustainable Design Entrepreneurship from the State University of New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. There, she learned about the Climate Reality Project from an instructor.

The Climate Reality Project was begun by Vice President Al Gore “He’s been doing this since 2005. It started small, on his farm,” says Arnoult. “Now it’s grown.”

Originally, the idea was to train other people to give Gore’s climate change presentation, as documented in the Oscar-winning 2006 film, An Inconvenient Truth. Since then, the organization has grown and branched out. Last year, Arnoult went through the rigorous application process to train with the Climate Reality Leadership Corps in Los Angeles. There, she met Vance LaVelle.

LaVelle spent 30 years in corporate America with AT&T, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Sirius XM Radio. She is now a consultant who splits her time between New York and Memphis. She says she first became interested in conservation because of her 93-year-old father-in-law, Dr. Herman LaVelle, a Memphis surgeon who built a timber farm in Fayette County. LaVelle says she had a climate epiphany on an airplane, while reading Gore’s book An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power while flying back to Memphis from Costa Rica, where her daughter and granddaughter live. She looked out the window to see a hurricane brewing in the Gulf of Mexico. “I was reading about superstorms and rain bombs, and I realized I was flying over it. It was no longer abstract to me,” she says.

“My late husband and I would go snorkeling in the Caribbean. You could just walk off the shore and see beautiful living coral and fish. I’m just back from St. Lucia in the British West Indies. There are coral reefs there, about 80 percent of it bleached. It’s so sad that my granddaughter will never have the opportunity see an eel come out of the coral.”

The three-day Climate Reality Leadership Training workshop LaVelle and Arnoult attended was the largest one yet. The class numbered 2,500 people, all of whom attended for free, thanks to the sponsorship of Bob Iger, Chairman and CEO of the Walt Disney Corporation. LaVelle says the training, some of which was delivered by Nobel laureate Gore himself, covered “pollution, change in weather patterns, and the migration of huge numbers of people from barren land that used to be rich with food. … We talk about how all this is impacting the life chain, the food chain, farming, and people’s livelihood, security, and civilization. Then, the tables are turned, and you hear about the solutions. That’s the good news. There actually are tangible solutions that we can take to stem the tide.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Duffy-Marie Arnoult, Vance LaVelle of the Climate Reality Project

The Green New Deal

The most complete vision of the Green New Deal is House Resolution 109. Introduced during the first session of the 116th Congress after the Democratic party’s historic victory in the 2018 midterms, it is a non-binding “sense of the House” resolution designed to create a road map for a sweeping climate program that would rival the national mobilization of World War II. It begins by citing the 2018 IPCC report’s findings that greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced from 40 percent to 60 percent by 2030, and taken down to net zero by 2050, in order to make the 1.5 C goal.

But the Green New Deal proposal doesn’t stop there. It draws a direct line between the climate crisis and what the authors call “several related crises,” such as declining life expectancy, clean water, healthy food, housing, transportation, education, wage stagnation, and income inequality. “… [C]limate change, pollution, and environmental destruction have exacerbated systemic racial, regional, social, environmental, and economic injustices by disproportionately affecting indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, de-industrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth.”

The bill resolves that it is the duty of the federal government to set the country on a course that would achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by creating new infrastructure based on renewable energy, such as solar and wind. In the process, it would create millions of “good, high-wage jobs and ensure prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States.”

The idea of killing two birds with one stone is not as far-fetched as it might sound. The New Deal, initiated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt when he took office during the worst of the Great Depression, transformed the nation in less than a decade, creating vast swathes of new infrastructure, including the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the public utility which brought electricity to rural Appalachia and presided over a vast building program of hydroelectric plants. In the process, New Deal jobs programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration lifted millions of people out of poverty and helped create the huge middle class that defined American society in the 20th century. The infrastructure the New Deal helped create has proven to be a public investment that has paid for itself many times over.

“I see the Green New Deal as an aspirational proposal,” says 9th District Congressman Steve Cohen. “Some of the specific proposals certainly aren’t going to happen anytime soon. Some of them may not happen at all. But the concept of putting people’s minds and attentions to climate change is very important. We are facing an impending climate crisis, and addressing that will require bold action. For decades, we’ve led the world in coal, oil, and gas development; now we need to lead in the rapidly growing clean-energy markets. We have a last, fleeting opportunity to preserve the planet we have harmed with carbon emissions. We can’t blow this for our future generations. The Green New Deal is a step in the right direction and will help us focus on making the necessary changes to our energy production.”

Senator Alexander also name-checked FDR when he called the proposal he made in response to the Green New Deal the New Manhattan Project for Clean Energy. “One Republican’s response to climate change,” says the short press release.

Some of Alexander’s proposals echoed the Green New Deal, such as encouraging investment in new battery technology that will be necessary to power electric vehicles and store energy produced by solar and wind sources. The Green New Deal and Alexander’s proposal agree on the low-hanging fruit of energy conservation, making homes and buildings more energy efficient. Both call for an increase in research funding. Alexander’s proposal emphasizes the development of advanced nuclear power plants — a carbon-free energy generation method that is the source of much debate in environmentalist circles — as well as fusion power, a technology that has been called “20 years away” from maturity for the last 50 years. Alexander ridiculed the Green New Deal as “an assault on cars, cows, and combustion.”

In the House, the Green New Deal proposal has more than 70 co-sponsors, including Cohen. Senator Alexander claimed to Politico to be working with fellow Republicans on possible approaches.

A Choice of Futures

At the Climate Reality Leadership training session in Los Angeles, and at a later, regional training session in Atlanta, LaVelle says they “learned a lot about the science behind climate change, the disproportionate impacts on people of color and lower income communities, the art of storytelling, and government structure. But what we’re really attempting to do is to activate communities: schools, faith communities, media. There’s less focus on government, and more focus on creating a groundswell; 100 percent renewable is one of our big campaigns.”

The Atlanta session took place in March, during the International Student Climate Strike, an international protest started by 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. “At my table, I had 16 college students from Georgia,” says Arnoult. “There was so much energy in the room. You don’t know what the future holds, but you know that everyone is there with a common goal.”

The Rev. Dr. William Barber II, leader of the current incarnation of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign, spoke to the assembled activists. “That’s one of the reasons I needed to be there,” says Arnoult. “We can’t remain in our silos. It’s fusion politics. There’s such an intersectionality with everything that is happening, with environmental causes, with social justice, with equality, with energy efficiency — all of it. You think one thing affects you, but this other thing doesn’t. They’re all related.”

While in Atlanta, Arnoult and LaVelle decided to start the Greater Memphis and Mid-South Chapter of the Climate Reality Project. The first push was to organize people to submit public comments ahead of TVA’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), which will determine the sourcing of all electricity generation in the system over the next 20 years. Unexpectedly, they got more than a hundred members to join their Facebook group in one week, and submitted dozens of proposals calling for TVA to set a goal of 100 percent renewable generation. “I did so much writing and explaining and recruiting that I barely got my own comments in,” says Arnoult.

LaVelle says concerns about the cost of building out a grid powered by renewables are misplaced. “Just as there is with any reinvention and change, it has to be thought through. Look at the costs of releasing carbon, and what’s happening to us. We’re not even thinking about those costs as being related to the behavior that we’re exhibiting. It’s like the aquifer here in Memphis. They were dumping coal ash at the plant, and acting like that’s not going to affect our water. That was part of how we appealed to TVA. We’re going to get lost in the old ways of doing things. The future is now.”

Like LaVelle, Arnoult is new to the world of organizing and activism, but she’s bursting with energy. “We’re just getting this chapter together,” Arnoult says. “We haven’t even had a chance to get together to figure out our strategy. I want to talk to people in the community. We have so many people trying to do good things here. We want to fill in the gaps. What’s missing? What can we do to bridge between communities? We have to bring in people from different walks of life. … We have a choice to make, and we have to make it now. There’s a critical window of 12 years where we can still have an impact. The TVA IRP is for the next 20 years. There’s still time to make choices and reverse it. Why wouldn’t we do that?”

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Traceywood | Dreamstime.com

Traceywood | Dreamstime.com