Everybody agrees that there was an air of kumbaya to the inauguration of Governor Bill Lee on a rainy January 9th inside War Memorial Auditorium. Part of it derived from the personality of the new chief executive, whose laid-back, inviting demeanor made him the gubernatorial choice last year of Tennesseans who doubtless felt overdosed by the bitter back-and-forthing of his two chief opponents for the Republican gubernatorial nomination — and who have not yet recovered the habit of treating Democratic statewide candidates with full seriousness.

Lee’s acceptance address at his inauguration was in keeping with his campaign persona — uplifting without being confined to specifics, a partial reason for its brevity. On the whole, the speech was not much longer than the bookend prayers of the event — the invocation and benediction. It contained the obligatory tribute to faith, family, and the ancestral virtues of Tennessee and Tennesseans.

And the new governor left no doubt that, for him, as for most prominent Republicans of our clime and time, “[g]overnment is not the answer to our greatest challenges.” As he intoned: “Government’s role is to protect our rights and our liberty and our freedom. I believe in a limited government that provides unlimited opportunity for we the people to address the greatest challenges of our day.”

Justin Wright, Tennessee State Photographer

Justin Wright, Tennessee State Photographer

And yet Lee served notice that there were areas of concern that he intended to move state government to address. Among them were:

Education: “More than a test score — it’s about preparing a child for success in life. A resurgence of vocational, technical, and agricultural education, and the inclusion of civics and character education, combined with reforms, will take Tennessee to the top tier of states.”

Poverty, urban and rural: “[W]e … have 15 counties in poverty, all rural, all Tennesseans. We have some of the most economically distressed ZIP codes in America — right in the heart of our greatest cities.”

Public Safety: “Tennesseans do want good jobs and schools, but they want safe neighborhoods, too. And while most neighborhoods are safe, our violent crime rate is on the rise in every major city. We can be tough on crime and smart on crime at the same time. For violent criminals and traffickers, justice should be swift and certain.”

And, as a necessary corollary to crime control and safety, “But here’s the reality, 95 percent of the people in prison today are coming out. And today in Tennessee, half of them commit crimes again and return to prison within the first three years. We need to help non-violent criminals re-enter society, and not re-enter prison.”

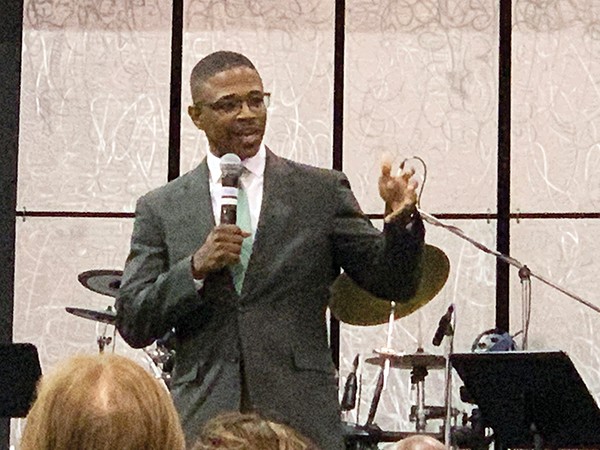

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Governor Bill Lee addresses the crowd at the War Memorial Auditorium in Nashville (top); Antonio Parkinson shakes hands with Lang Wiseman (below).

It is that part of the new governor’s commitment that has engendered excitement among his reform-minded constituents, as well as among legislators — many of them hailing from Memphis and Shelby County [see sidebar] — and among movers and shakers at large.

One of the latter is Hedy Weinberg, head of the Tennessee chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, who, in a luncheon address to the Rotary Club of Memphis last week, made a point of proclaiming her confidence in Lee’s bona fides on the subject of criminal justice reform.

She pronounced the governor to be “very committed to criminal justice reform” and went so far as to say, “we speak the same language” on that issue.

If Lee lucked out with that endorsement from the ACLU’s Weinberg, he had worse fortune on another occasion. In the immediate wake of the inauguration, the new governor went to a ceremony at Tennessee State University honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. There, he delivered a convincing testimony regarding his intention to provide more effective and humane solutions to post-conviction offenders seeking to re-enter society. He did well, but then, as veteran scribe Erik Schelzig chronicled it in The Tennessee Journal:

“… Lee then took a seat behind the lectern [and] Rev. William Barber II, the head of the Poor People’s Campaign, which is a revival of King’s effort that has mounted recent acts of civil disobedience in Nashville. … [Lee] most notably stayed seated when Barber called on anyone opposing President Donald Trump’s border wall and supporting Medicaid expansion to stand. Barber thundered that King would have favored a series of policies opposed by most Republicans, including a living wage, a ban on assault weapons, and universal health care (he denounced it as a “shame and a disgrace” for Tennessee to have failed to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act). “The crowd loved it.” But Lee, meanwhile, sat stoically and uneasily.

Asked about this in an interview with the Flyer, Lee acknowledged his discomfort and took a stab at presenting an alternative view: “The biggest challenge we have in health care is that we have skyrocketing costs that people can’t afford. So my plan focuses on reducing the cost of health care and improving the health of people, which would decrease costs as it improves people’s well-being. It’s about how we can make people healthier. A large percentage of our current health-care needs are associated with preventable chronic disease.”

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris (above) and newly elected Tennessee Governor Bill Lee have both made juvenile justice reform an issue in their approaches to government.

Medicaid expansion is not the only subject on which the state’s new governor possesses views that some would find contrary. School vouchers are another. Avowed progressives oppose it on grounds of separating church and state, and the suburban conservatives of Shelby County have soured on it as a threat to the tax-supported municipal school systems they now have a vested interest in. Even state Senator Brian Kelsey of Germantown, the arch-conservative supporter of voucher measures for 16 straight legislative sessions chose last year not to introduce his usual measure to divert public funds selectively on behalf of students at private institutions.

Lee is a resident of Williamson County, an expansive suburban area just south of Nashville, where House Speaker Glen Casada, who has proposed reviving voucher legislation, also hails from and where vouchers are regarded less warily.

The governor prefers to refer to the subject as a matter of school choices. “I think the choices for parents are very important. The most important thing is that every child have access to a good education. We need to strengthen our school system. Part of the way to do that is to allow parents to have choice.

“Education savings accounts, charter schools, public school choices: These are all things that I’m willing to look at to improve the opportunity for education for every kid.

“My interest in school choice — that’s a broad choice for all areas in the state. That’s an interest in elevating the quality and outcomes of our school system all across the state. Vo-tech and agricultural and CTE (that’s career technical education). There’s a lot of phraseology and terms around that, but primarily it is expanding opportunities for kids in our schools, more skills-attainment for our kids, and opportunities for success in life. My real interest there does lie in vocational- technical and agricultural-educational public schools system.”

Courtesy American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee

Courtesy American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee

Hedy Weinberg

Somewhere in there are surely points for possible compromise.

Another controversial view ascribed to Governor Lee is an openness to the idea of “constitutonal carry” or the virtually unlimited (and unlicensed) privilege of citizens to carry firearms — a severe reduction that a neighboring state like Mississippi has already adopted.

Lee is not quite there yet. “All I’ve said is that I would sign a constitutional carry bill if one passed my desk. It’s not an issue that I’m leading on. I try to stay focused on things that we’re trying to present in a legislative package. These are around vocational education, around recidivism, and job development. Those are the things we’re focusing on.”

Other things that Lee focused on in the Flyer interview, which took place last Friday at the beginning of his first weekend as governor:

Possible consequences for state government of a federal government shut-down: “My understanding is that the most recent one is over, at least for some period of time. We won’t have to deal with it for several weeks anyway. But I certainly want to stay on top of things. I’ve had folks in our administration start looking for what effects could come, if a shutdown would resume or continue, but that’s about as far as we’ve got.”

Spending and governmental priorities: “I’ve asked every department to lay out what it would look like to cut two percent from their budgets. We certainly will take some of those cuts. My overall goal is to reduce government spending to the degree that we can — and certainly to minimize potential increases. All of those cuts are on the table to be taken, but even if not, they are valuable in determining priorities and what to do with the resources we have. But we have opportunities to cut in every department. I believe in limited government.”

His first actions as governor: “I put out executive orders that strengthened orders previously in place on ethics, transparency, and discrimination. My first executive order was one strengthening our aid to rural counties — particularly those 15 that are under the poverty line.”

The West Tennessee Megasite: “I actually spent about an hour today with the Economic Development Commissioner, with our deputy governor, and with my senior adviser Brandon Gibson, who is from Jackson. We were assessing the megasite, exactly where the asset is today, what is necessary to get it shovel-ready, what are the options, and what are the prospects. It’s very important to me and to the state, so I’m spending time here in my first week getting up to speed with a complete in-depth understanding of the megasite.

“I don’t have an idea yet of the additional funding required. One of the questions I asked today was how many dollars it would take to get it ready. I want to know what it takes for a tenant to occupy it, in short order.”

Plan to raise Shelby County to the rest of the state: “I met this morning with our senior team, including Deputy Governor Lang Wiseman. He’s from Memphis. We talked about economic opportunities, job creation, and economic incentives to attract industry into West Tennessee. When you think about educational reform, there’s no place more appropriate than Memphis as a place to do that. It’s one of the largest cities in the state, and it has some of the greatest opportunities for improvement in our educational system. The accelerated transformation of Shelby County is important if we want Tennessee to make it to a leading place in the country.”

Summing up: “I believe that Tennesseans are a unique group and that we have a real opportunity. There is more that unites us than divides us. That’s the way I ran my campaign, and it’s the way I want to govern. Hopefully, that’s absolutely what will happen.

…

Justice Reform: A Consensus Point

As Hedy Weinberg of the Tennessee ACLU observes, the Tennessee General Assembly has in recent years seen an increasing incidence of cooperation between legislators of the left and right on bills aimed at criminal justice reform. Though in an address last week to members of the Rotary Club of Memphis she noted such remaining stands of potential obstruction as the bail-bond industry, Weinberg hailed what she saw as a dawning era of bipartisan agreement on reform issues.

Governor Lee has singled out criminal justice reform as a major governmental aim and would seem to be actively seeking out partners.

One of the interested parties is Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris, who has made juvenile justice reform a major issue in his own approach to government. Harris, who vigorously protested the decision of the U.S. Department of Justice to cease its monitoring activities over Juvenile Court, has called for the demolition of the antiquated existing facilities for housing juvenile offenders, and is attempting to persuade the Shelby County Commission to create a new assessment center for juveniles, and to pony up the sources for an upgraded new detention facility that offers the youth inside it access to fresh air, recreation, and abundant classroom activity. Only this week, he persuaded the commission to authorize the first financial component on what will be a $25 million facility and persuaded commissioners further to give it the working title of Youth Justice and Education Center.

Harris, as a Democratic state senator, pioneered in bipartisan criminal-justice reform efforts, sometimes in tandem with such opposite numbers as Republican state Senator Brian Kelsey of Germantown. He has also asked newly sworn-in District 33 state Senator Katrina Robinson, among others, to carry a remedial package of legislation on behalf of the county.

Robinson has jumped into the criminal-reform conversation in dramatic fashion, sponsoring a plethora of bills on the subject:

Senate Bill 62 would require the Department of Education to develop rules, to be adopted by the state board of education that include procedures for providing instruction to students incarcerated in juvenile detention centers for a minimum of four hours each instructional day.

SB 63 would expand career and technical education programs in the middle school grades and require the Board of Career and Technical Education to plan facilities for comprehensive career and technical training for middle-school students.

SB 65 and SB 85 would establish a center for driver’s license reinstatement and remove authorization to suspend, restrict, or revoke drivers’ licenses for nonpayment of fines, court costs, and litigation taxes for driving offenses, upon proof of inability to pay.

SB 69 would reduce the sentence a minor who commits first-degree murder is required to serve before becoming eligible for release from 51 years to 25 years. (This is one of several pieces of legislation introduced by the Shelby County delegation that indirectly reference the case of Cyntoia Brown, for whom outgoing Governor Bll Haslam recommended clemency as one of his last acts.)

Other legislative introductions related to criminal justice reform:

House Bill 17 by another first-term Memphis legislator, state Representative London Lamar, also related to the Cyntoia Brown case, would establish the presumption that a minor who is the victim of a sexual offense or who is engaged in prostitution holds a reasonable belief that the use of force is immediately necessary to avoid imminent death or serious bodily injury.

HB 47 by state Representative Antonio Parkinson would allow a person entitled to seek expunction from the record of a crime to pay an additional $250 fee for expedited expunction, to occur within 30 days of a court order granting expedited expunction.

HB 30 by state Representative Barbara Cooper would permit certain incarcerated persons who are allowed to enroll in courses offered by a community college or Tennessee college of applied technology pursuant to an approved release plan to receive a Tennessee reconnect grant.

The legislative session has just begun, with full committee and floor action commencing this week. The signs are clear that other Shelby County legislators and other bills on the subject of justice reform will be heard from before the deadline for introducing new bills.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Justin Wright, Tennessee State Photographer

Justin Wright, Tennessee State Photographer  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Courtesy American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee

Courtesy American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee  JB

JB