Lately, you may have heard folks asking, “Are you going to that ‘Americana’ fest this weekend?” But the festival and awards show about to hit our town isn’t Americana. It’s the Ameripolitan Music Awards, and its founder, Dale Watson, wants to make sure you know the difference.

“It’s original music with a prominent roots influence,” he says. “As opposed to Americana, which is original music with a prominent folk and rock influence. Ameripolitan starts with Jimmy Rodgers, then Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, and so on, and then moves on to people like Merle Haggard. They’re a natural growth of the tree.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Dale Watson

“In the late ’70s and early ’80s, greed went nuclear on country music, and made the tree morph into some unrecognizable monster, where Florida Georgia Line is considered on the same tree as Hank Williams, which it never should be. That’s some nuclear waste shit that happened to the roots. Americana, I think, starts with Woody Guthrie. And goes from him to people like Bob Dylan and Steve Earle. It goes along that tree. Which is great music, I’m not knocking it, but it’s not my influence.”

When he was planning his first Ameripolitan Music Awards show in Austin in 2014, Watson says Nashville’s AmericanaFest organizers contacted him for a genre-policing pow wow. “They said, ‘There’s no need for you to do this. The music you’re talking about is under our umbrella.’ I said, ‘Well, we’re getting wet. We’re not getting any kind of love whatsoever.’

“It all started with Blake Shelton. He said, ‘Nobody likes this kind of music. Nobody wants to listen to your granddad’s music.’ Blake Shelton is a multi-millionaire trying to buy his way into being today’s country music standard. And by today’s country music standard, he probably is. But once you do country music with hip-hop in it, I think you’ve lost all credibility.”

If Watson is trying to celebrate genres now ignored by the mainstream, from classic and outlaw country to rockabilly and Western Swing, he emphasizes that Ameripolitan artists are not just milking the nostalgia circuit. “Like John Lennon said, ‘Originality comes from your inability to imitate your influences.’ And I think you can tell my influences. You can tell I’ve listened to Merle Haggard and Johnny Cash and Elvis and Bob Wills. I wear my influences on my sleeve. But if people call it retro, I say, ‘No, these are new songs. Just because you build a house with a hammer — an old tool — doesn’t make it an old house.’ I’m just using an old tool, you know?”

Watson and thousands of music fans who love music created with old tools, will gather in Memphis clubs throughout the city this weekend and into next week, celebrating the best exemplars of their craft. All concerned would surely agree when Watson, quoting Kris Kristofferson, proudly states their home truth: “Good music doesn’t have an expiration date.”

— Alex Greene

Rosie Flores

Bringing It All Back Home … Again

Delving into the discography of Rosie Flores, the two-time Ameripolitan Award winner and self-proclaimed “Rockabilly Filly,” you could easily think she followed the time-honored path from conventional country to gradual experimentation with the edgier sounds of rockabilly and blues. But you would think wrong.

Though her first records in the late ’80s and early ’90s were largely country affairs, they already marked a full-circle evolution of sorts for the songwriter and guitarist. As early as 1987, the L.A. Times was writing that “it has taken her more than a decade ‘to come full circle,’ from traditional country, to rockabilly, to something called cow-punk, and now back to traditional country.”

Rosie Flores

Indeed, Flores’ last band before going solo was the California cow-punk group the Screaming Sirens. But taking the ebb and flow of tradition(s) in stride was second nature to this musical omnivore.

“Before the Screaming Sirens, I was in a country rock band that was influenced by Gram [Parsons] and Emmylou [Harris], called Rosie and the Screamers,” she recalls. “That was in 1976. It was all country rock and steel guitars. Kind of between Fleetwood Mac and Gram and Emmylou. The guitarist was really into Peter Green, from the original Fleetwood Mac. And it was phenomenal, the instrumentals we would go into. I had been a budding guitar player since Penelope’s Children, which was my first band when I was 16. I was the one and only guitar player, so I had to play lead and do all the vocals. And write all the songs.”

But don’t let that reference to her days as a “budding guitar player” mislead you. Flores has long been a powerhouse axe-master, so much so that she’s been featured in Premier Guitar Magazine, where she told interviewer Joe Charupakorn, “Make me sound like I’m a big, fat, sweaty guitar-player guy. Don’t think about my gender. I’ve said from the beginning, whatever you do, don’t think, ‘This is Rosie, I have to make her guitar sound sweet.'” Charupakorn wrote of “Flores’s kinetic double-stop bends and Bigsby-bent trills,” and how she was “throwing down equally greasy mayhem with Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister and blues sensation Joe Bonamassa, as she duck-walked across the stage at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame tribute to Chuck Berry.”

Her strength as a player is sometimes lost on fans because of her penchant for hiring top-notch band members, including guitar players. “Fans ask, ‘Why do you have another guitar player?'” Flores says. “‘I came to hear you and you’re giving him all the solos.’ Well, I really love great guitar players. That’s why it was so perfect to have Kenny Vaughan, my favorite roots guitar player, on the new record.”

That record, Simple Case of the Blues, just dropped last week, and it’s another stylistic left turn, and yet another ‘full-circle’ return to her roots. “I am certainly circling back to the blues, because that’s the first guitar stuff I ever played, when I was learning,” she notes. “You know why? Because I was a pretty big Rolling Stones and Beatles fan. I was playing chords to the pop music of the Beatles and then playing lead guitar parts to the blues. For many guitar players starting out, they first learn to play in the pentatonic scale, which is pretty easy to understand. And for a kid, that was a great way to start playing guitar at age 15. So I could start jamming. One of the first songs I ever learned to play was a Rolling Stones cover of a Wilson Pickett song, called ‘If You Need Me.’ And I put that on the new record just to circle back where I started.”

Of course, the mainstay of Flores’ career since the mid-’90s has been rockabilly, which she delivers with panache. Perhaps that’s what earned her twin awards for Best Rockabilly Female and Best Honky Tonk Female at the first annual Ameripolitan Music Awards in 2014.

And since leaping into that genre, so full of swinging cat daddies, she’s also been a champion for women who played a pivotal role in the style’s ascendance. Her Rockabilly Filly album pairs her with many starlets of the sound’s earlier days, such as Wanda Jackson and Janis Martin. So profound was the experience of working with the latter that Flores went on to coax Martin out of retirement for one last record, eventually released posthumously as The Blanco Sessions.

“I contacted her and said, ‘Can I produce the record?’ I just knew she deserved to have new recordings, and I knew so many great rockabilly players we could use. And then she said, ‘Well, I’m kind of tired of rockabilly. I’d like to do a blues record.’ And it is very bluesy, but it’s Janis, it’s who she became. From her little girl voice to her more mature voice. And I can relate, because I’m the age that she was when we made her record. And I can see that my voice has gotten a bit smoky and has a little dust around the edges.”

Flores’ acknowledgment of great women artists will continue at this year’s Ameripolitan Awards, when she joins several great women players to pay tribute to songwriter Cindy Walker, composer of hits from the ’40s to the ’80s. “Songwriters know who she is,” says Flores. “Her big hit, ‘You Don’t Know Me,’ was one of the most beautiful songs I’d ever heard when I was growing up, and then I found out she wrote it, I was like, ‘I wanna be her!’

“When you’re a musician, you study everything,” Flores muses. “If you’re a true musician, that’s what you’ll do. You’ll be part of everything. I’m hoping that will happen with Cindy Walker’s music, and that younger people will study her songs and learn from her. I’m 68 and I still do.”

Flores will also be taking the stage for her own set at Blues City Cafe on Saturday. Leading a trio, she’ll have plenty of sonic space to show off her guitar chops. But it may be those moments after the show that she looks forward to most. “It’s fabulous that I can still put records out and have people show up. And Dale Watson and I have a similar pattern with our fans. We get out there and talk to them, get to know them and hang out. When we’re done with our show, we don’t go hide behind our curtain. We get out and see who’s there. I can see the enjoyment in Dale’s eyes and personality. And I can relate to that.”

— AG

Larry Collins

The man who helped inspire surf and prefigured punk.

Larry Collins has stories. In the 1950s, when he was a kid star gigging on TV in Hollywood, he was fully immersed in a world that brought him into contact with everybody from cowboy star Gene Autry to film icon Robert Mitchum to Walt Disney’s Mouseketeers. Elvis gave him the nickname, “Little Cat.” Bob Wills, leader of The Texas Playboys (and the Elvis of Western Swing), puked all over his rhinestone and fringe-laden Nudie suit.

Before he was old enough for middle school, Collins had met and performed alongside some of the 20th century’s most popular musicians. He can spin tales about teen heartthrob Ricky Nelson and electric guitar virtuoso Dick Dale, both of whom dated his sister. But the better story is Collins’ own unique, if understated, role in shaping the West Coast sound and high-octane honky tonk, from country boogie and surf to the hot-rod guitar rumble of early rock-and-roll.

The Collins Kids, Larry (left) and Lorrie Collins

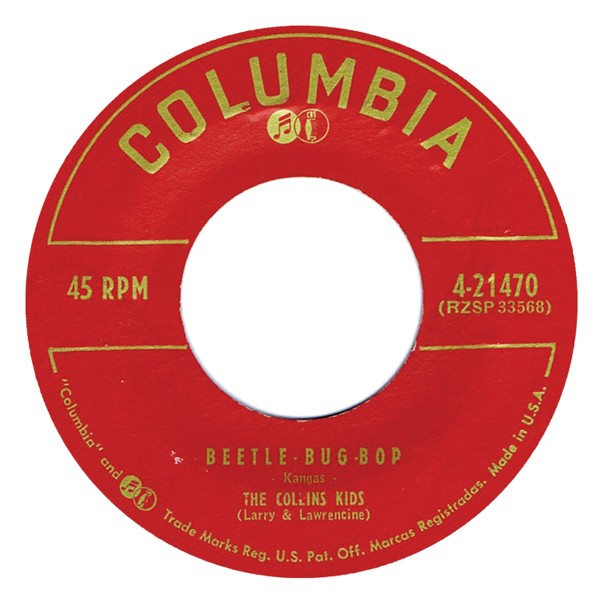

If you don’t recognize Collins’ name, maybe “Delta Dawn,” the country tune he co-wrote with Alex Harvey, will ring a bell. But 13-year-old Tanya Tucker’s 1975 hit recording of that song came relatively late for this early starter — years after Larry (Lawrence) and his sister Lorrie (Lawrencine) regularly lit up TV screens all over Southern California as the Collins Kids. She was a luminous teenage songbird who wrote her own rockabilly songs and played guitar like one of the boys. He was a pint-sized Tasmanian Devil, straight out of the old Warner Bros. cartoons — a human tornado able to sing high harmonies while dancing in manic circles and trading licks with legendary pickers such as Joe Maphis and Merle Travis. Larry and Lorrie cut upbeat novelty singles like “Beetle Bug Bop” and the Bo Diddley-inspired rocker, “Hoy, Hoy, Hoy,” setting a high bar for innocent-yet-intense West Coast rock.

The Collins Kids became regulars on Tex Ritter’s Town Hall Party in 1954.

They signed a record contract with Columbia two years later and were marketed like a children’s act, in spite of records like, “Whistle Bait,” the turbo-charged 1958 single that’s sometimes ahistorically identified as the first “punk” record. Larry’s lustful pre-teen vocals and raging proto-surf guitar don’t just point the way, they clear a path. “Whistle Bait” sounds every bit as weird and unhinged today as it must have when Eisenhower still occupied the Oval Office.

Collins doesn’t take a lot of credit for his work in co-writing the David Frizzell and Shelly West hit, “You’re the Reason God Made Oklahoma” for Clint Eastwood’s 1980 film Any Which Way You Can. But even if Collins didn’t pen all the lyrics, the song’s plaintive conversation measuring the emotional distance between Tulsa and Los Angeles, cuts right to the heart of his artistic journey.

“I’ll take credit for the name,” Collins says.

The show business opportunities that prompted Larry and Lorrie’s move from Oklahoma to Hollywood were nothing like the difficult, Depression-era migration Merle Haggard sang about in songs like “California Cottonfields.” But even for a couple of child prodigies, the stigma related to their own move lingered.

“We were definitely Okies, and we were called that a lot,” Collins says, looking back at when the O-word still had bite. “Mom didn’t like it.”

The Collins Kids may have learned to play their instruments in barns and honed their skills singing in church and at family gatherings, but there was nothing provincial about the sound. As a 9-year-old, Larry was paired with Joe Maphis, the versatile player who wrote “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke, and Loud, Loud Music,” and who was nicknamed “king of the strings” due to his ability to play nearly any instrument he picked up.

“There were no rehearsals,” Collins says. “Whenever we’d do an instrumental, we’d go into a small room downstairs from the stage,” Collins recalls. “Joe would say, let’s play ‘Wildwood Flower,’ and he would kick off ‘Wildwood Flower’ just flying. I’d just listen. Nobody told me, ‘your finger goes here,’ or, ‘You hit a C first.’ I just played it. We’d run through things one time,” says Collins.

Collins learned from Maphis and Travis and others, but he describes his abilities as “a gift.” He says his licks were more inspired by sounds he heard listening to famous border DJ Wolfman Jack. That’s where he first heard Bo Diddley and where he fell in love with R&B horn sections. “A lot of the rockabilly riffs I got, I got from listening to the horns,” he says.

The Collins Kids started out as a pair of solo acts. Lorrie had already performed on the Louisiana Hayride on a bill with Hank Williams before Larry had even gotten his first Stella guitar for Christmas. But a family act made sense for live TV, and by the time the Collins Kids signed with Columbia in 1956, they were seasoned veterans of a notoriously wild and woolly medium.

To illustrate how crazy things could get behind the scenes, Collins tells the story of the night when Bob Wills got too drunk to play his fiddle and locked himself in a Cadillac Fleetwood. For some reason, the adults all thought it would be a good idea to send 12-year-old Larry to talk the pickled bandleader into making his gig. According to Collins, Wills only laughed and kept swigging on his bottle. Then he patted the boy on his knee, promised him he’d “understand everything” some day and proceeded to throw up.

When Collins returned, covered in vomit and bearing bad news, it was decided that the best thing to do to keep the crowd from rioting was to strip the kid out of his soiled clothes, dress him up like Bob Wills, send him out on stage, and hope the audience would think it was funny. “Dead ass silence,” Collins says, describing the moment he stood on stage in a ridiculous, makeshift Bob Wills costume with an oversized cigar. Collins started playing Wills’ song “Maiden’s Prayer,” and the house erupted in applause.

“Live TV,” Collins says, laughing off the insanity.

The Ameripolitan Music Awards will honor Collins with its Keeper of the Key award this year, a lifetime achievement recognition for artists who have played a significant role sustaining Ameripolitan traditional root forms. Past winners include country guitar wizard Junior Brown and psychobilly torchbearer Rev. Horton Heat.

— Chris Davis

Editor’s note: Click for a full schedule of performances and events for the Ameripolitan Music Festival