Back to “normal” could take a year, if nothing else changes in Shelby County. COVID-19 vaccines are just now beginning to move us forward through the dark tunnel of death, illness, and disruption that we’ve been trapped in for 10 months. While there’s hope — make no mistake — it’s a long, long tunnel.

That was the takeaway from public health officials in Shelby County last week. Vaccines are scarce, their delivery is unpredictable, and it will take a long time to get the medicine into the arms of enough people here to get us to the point where we can even fantasize about throwing our masks away. If things stay the same, that could take a year, according to Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris.

Only two vaccines are currently approved for use in the United States: one from Pfizer-BioNTech and another from Moderna, each requiring two doses. Tennessee now expects to get 90,000 collective doses of the vaccines each month. At that rate, immunizing enough of Tennessee’s 6.8 million residents to gain herd immunity would take a year, Harris explained during a public briefing last week from the Memphis and Shelby County COVID-19 Task Force.

But he added that some “game changers” are on the horizon. New vaccines could become available. Some existing vaccines may be approved that would require only a single dose, essentially doubling supply.

None of that is concrete yet, Harris said last week, but it gave him hope: “So there is light at the end of the tunnel; there are reasons to be hopeful, and we are working really hard to get this done. But we do need to recognize, this tunnel is long and it is likely to have twists along the way. It will require all of us to make adjustments.”

What kind of adjustments? Consider that for a good portion of last week, Shelby County officials weren’t sure when they’d even get more vaccine. Their initial 12,000 doses had run out and they simply had no idea when they’d get more.

The Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) confirmed late Friday that Shelby County could expect 8,900 each week for the month of January. The health department would administer 4,000 doses each week, with the remainder going to the county’s hospitals. In a news release issued Friday, the health department announced it had opened appointments for those in priority groups to get the vaccine this month. Another announcement followed about an hour later stating all appointments had been filled.

The vaccine rollout has been bumpy, lurching, and uneven. But it’s early yet and Shelby Countians will certainly have to adjust their expectations.

To calibrate, dial back to March 23rd, 2020, when just 93 people had tested positive for COVID-19 in the entire county (the figure is higher than 80,000 today). Potential positive tests were screened first to assure they were eligible for testing by a state-run lab. As we know now, testing is widely available — just hop in your car and go — and “anyone who thinks they need a test should get one,” according to the Shelby County Health Department (SCHD). Today’s testing availability surely would have seemed a marvel to Shelby Countians back in March. Perhaps the same will be true for vaccinations in the near future.

Where We Are Now

Vaccines currently flow from two manufacturers to the U.S. government, to the state, and, then, to the various health departments and hospitals in counties across the state. So far, the U.S. has ordered 400 million doses of the vaccine — 200 million from Moderna and 200 million from Pfizer. The country will need at least 655 million total doses to vaccinate more than 328 million American citizens twice.

As of Sunday, January 10th, The Washington Post reported that 6.7 million people had been vaccinated in the U.S. Around 22.1 million vaccine doses had been distributed with 24.1 million more scheduled for delivery this week, all of it designated to vaccinate the 97.4 million Americans (healthcare workers, first responders, the elderly) prioritized to get the vaccine first. The rollout’s reality so far has been well behind the Trump administration’s stated goal to vaccinate 20 million people by the end of 2020.

Tennessee has been allotted 462,650 doses of the vaccines. As of Sunday, 197,000 people had received a shot, covering roughly 3.4 percent of the people prioritized to get the vaccine and about 2.9 percent of the state’s population. The Post said 463,000 more doses were slated for delivery to Tennessee this week.

Shelby County got about 12,000 doses of the state’s first allotment. In the first seven days, healthcare workers here administered doses to 9,500 people. The rest were to be given out this week. Some doses of the vaccine became available as people missed their appointment times — enough so that the health department temporarily opened access to those in lesser priority categories, including those over age 75 and funeral home workers. This practice ended last week as the rest of the doses were given to those in nursing homes or other congregant living settings.

A Vaccination Workforce

Let’s say Shelby County suddenly had 1.3 million doses, enough to vaccinate everyone in the county twice. Overcoming that barrier comes with its own barrier. Who will administer all those shots?

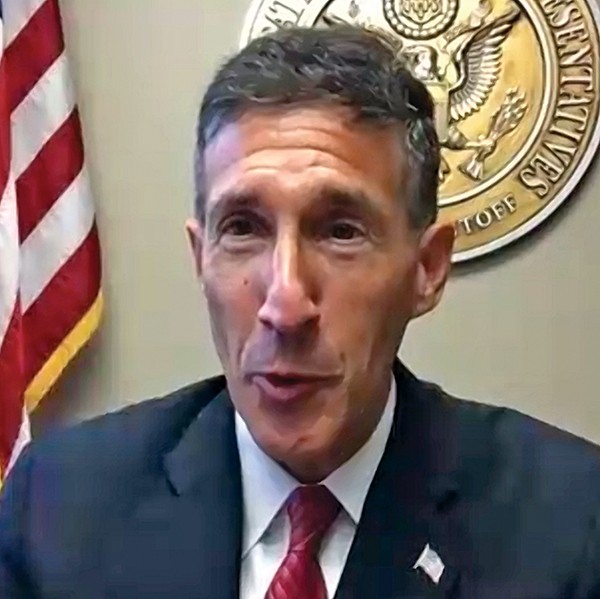

“There is no cavalry coming,” says Dr. Scott Strome, executive dean of the College of Medicine at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC). “It’s just not there.”

Strome explains that flu vaccines, for example, are routinely given at doctors’ offices, drug store chains like Walgreens and CVS, hospitals, and elsewhere. But that’s not the case for the COVID-19 vaccine, specifically the one from Pfizer, which must be stored at a very cold temperature. It comes with a host of specific regulations in order to be able store it and deliver it to patients. Few places are equipped to meet those requirements, certainly not a parking-lot, pop-up type of location like those used with the flu vaccine.

For now, administering the vaccine is limited to those places with medical staff and proper storage facilities. So, no matter how much we get, Strome says, it’ll have to squeeze through a bottleneck of basic human resources: “You’re going to have to build a workforce to actually vaccinate people.”

Strome says UTHSC, the professional healthcare schools in the area, and other local leaders here are working to do just that. They’re teaming up to train, organize, and mobilize healthcare students, to turn them into a vaccination workforce.

We’ve seen this move from Strome before. He led healthcare students to open one of the first drive-through testing stations at the Mid-South Fairgrounds in March. Back then, he said that the pandemic had interrupted the education of UTHSC’s 700 students and that testing “is their way to give back to the community.”

New Shots, New Doses

Even if Shelby County did have an adequate vaccination team, it doesn’t have 1.3 million doses, not even close. With the promised 8,900 doses for the next three weeks and the original 12,000, we’d be able to vaccinate about 6 percent of Shelby County’s population, about 39,000 of the 656,000 we’d need for herd immunity. But there are some possible game-changers on the horizon.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), told the Associated Press (AP) last month that to have enough vaccine to cover up to 85 percent of the population — his projection for herd immunity — “you’re going to need more than two companies” making approved vaccine doses. That is happening.

The World Health Organization (WHO) said that as of January 6th, 235 vaccines were in development across the globe. Sixty-three of those were in clinical development (human trials) and 172 were in preclinical stages.

The Trump administration promised AstraZeneca’s vaccine would be ready by October 2020 and that 300 million doses (at a cost of $1.3 billion) would be available by January under Operation Warp Speed. That vaccine candidate has not made it through the U.S. approval system but was approved in the U.K. (Officials now say the vaccine might not be ready for American arms until April.)

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

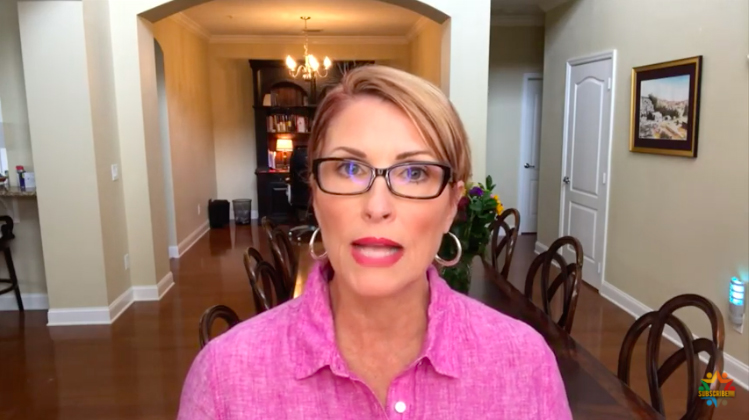

Dr. Aditya Gaur

The AP said the “next big vaccine news” may come from Johnson & Johnson (J&J), aiming for a one-dose vaccine with help from Memphis. In November, UTHSC and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital offered a testing site for J&J’s Phase 3 clinical trial. Of the global trial’s nearly 45,000-person sample (all 18 and older), 300 of them were tested in Memphis. Enrollment in the trial has closed, says Dr. Aditya Gaur of St. Jude’s infectious diseases department, and participants here are getting routine check-ups, looking for any COVID-19 infections. Results of the trial will be driven by the number of infections, Gaur says, but they could come as soon as a month or two.

Gaur notes the overall study will last two years. Before then, the vaccine could receive emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), just as the Pfizer and Moderna drugs did, and “then we would have one more vaccine that can become part of what is being offered to individuals around the world,” Gaur says. “It’s a daunting task to provide a vaccine and provide a vaccine quickly, such that one can truncate the trajectory of infections that are there.”

If proved effective, the J&J vaccine, Gaur says, would “be a very good value-add” to drugs already on the market. The reason is simply because it would take only one dose. Achieving that would remove patient volume from the vaccine line, and the complexity of getting patients to come in twice.

A single-dose vaccine was something that Mayor Harris mentioned in his remarks last week. “It’s possible that one of those companies may get approval for a single-dose vaccine. It is conceivable — theoretically — that if that happened, that we may be able to cut our vaccination process in half.”

While the world waits for more medicines to make it through government approvals, some are looking to stretch what we already have for a wider spread of vaccines. British health officials surprised many public leaders and public health professionals around the world recently when they announced that they would delay the second dose of the vaccine in favor of inoculating more people with a single dose, first.

The British Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) issued a statement on December 31st to note the shift in strategy. Those countries (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland) will now vaccinate as many people as possible with the first dose of the vaccine, rather than give two doses to high-priority groups, like healthcare workers and the elderly.

“In terms of protecting priority groups, a model where we can vaccinate twice the number of people in the next two to three months is obviously much more preferable in public health terms than one where we vaccinate half the number but with only slightly greater protection,” reads the letter.

Current protocols approved in the U.S. call for an interval of 21 days between the first and second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. For the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, the interval is 28 days between the first and second dose. U.K. health officials said their review of late-stage, drug-trial results led them to believe it would be okay to wait around three months between the first dose and the second.

They said the first dose of the vaccine is “very important for duration of protection” while “the additional increase of vaccine efficacy from the second dose is likely to be modest.” They noted that the “great majority of the initial protection from clinical disease is after the first dose of the vaccine.”

The move met skepticism from health officials in other countries. On January 4th, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a letter that any changes to approved vaccine protocols is “premature and not rooted solidly in the available evidence.” Hahn said drug-trial patients who did not get the second dose within three or four weeks weren’t followed closely enough and the FDA could not conclude anything definitive yet about patients getting just one dose.

“If people do not truly know how protective a vaccine is, there is the potential for harm because they may assume that they are fully protected when they are not, and, accordingly, alter their behavior to take unnecessary risks,” Hahn said in the letter.

Similar skepticism on the U.K. move has come from scientists and doctors in Great Britain and in the World Health Organization, all of whom expressed concerns about the science.

The U.S. is reviewing another dosing maneuver that would get the vaccine into more Americans more quickly. Scientists at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are studying the Moderna vaccine to learn whether a half dose would be as effective as a whole dose. If so, the move could double the supply and make the vaccine more widely available.

While a December 17th review of the protocol seemed promising, the FDA’s Hahn, again, did not support it. “We know that some of these discussions about changing the dosing schedule or dose are based on a belief that changing the dose or dosing schedule can help get more vaccine to the public faster,” Hahn said in a statement. “However, making such changes that are not supported by adequate scientific evidence may ultimately be counterproductive to public health.”

The incoming Biden administration, however, appears to be on board with Britain’s one-dose strategy. President-elect Joe Biden said last Friday that he aimed to release nearly every available dose of the coronavirus vaccine when he takes office, a break with the Trump administration’s strategy of holding back half of U.S. vaccine production to ensure second doses are available.

The Vaccine’s the Thing

So there is hope for change on the horizon. Mass vaccine plans and other fresh ideas are out there. We’ve come a long way since last March. But we live in a county that just surpassed 1,000 COVID-19-related deaths on Friday, and reports of deaths are rising day to day. The weekly average of positive tests has also risen sharply. Hospitals are jammed. The number of active cases — the number of people known to have COVID-19 in the county — usually hovers around 7,000, a figure that had been at 2,000 in October. Health officials announced last week that COVID-19 was the third-leading cause of death in 2020, just below heart disease and cancer. Even so, Shelby County is doing far better (on a per capita basis) than most of Tennessee, a testament that city and county leaders were right to take aggressive positions early on.

The COVID-19 holy trinity — masks, hand washing, and social distancing — has been preached to residents here time and time again, in speeches, in commercials, in briefings, and on flyers, ads, internet memes, and by politicians, athletes, and celebrity chefs. Has it helped? Probably. But precise data on the effectiveness of the campaign is difficult to determine.

Capacity at gyms has been cut to 50 percent, including staff. Bars are closed. The capacity at restaurants has been cut to 25 percent, and customers must be six feet apart. Even while restaurants remain open, SCHD Health Officer Bruce Randolph says “just because something is legally permitted does not mean that it is medically advisable.”

A new Stay-At-Home order won’t lift until January 22nd, and it hasn’t — so far — changed any key COVID-19 figures in the county. Randolph says data from the change wasn’t expected until this week and, so, “the jury’s still out” on whether Stay At Home has worked this time. With new data, Randolph says a further lockdown order may be needed.

Limits on large groups have also been a bedrock of any health directive issued to ease human contact in Shelby County. At various times, gathering sizes in the county have been limited to 50 people, and even down to 10 on occasion.

Daily Memphian reporter Jane Roberts asked Randolph last week what else was left for the health department to do — after closing businesses, preaching hygiene, and ordering people to stay home. People must “become more responsible and more compliant. We were doing things to educate and reinforce. … but the bottom line is that people themselves must do the right thing,” Randolph told Roberts. “We shouldn’t have to just completely shut everything down in order to get you to do that right thing.”

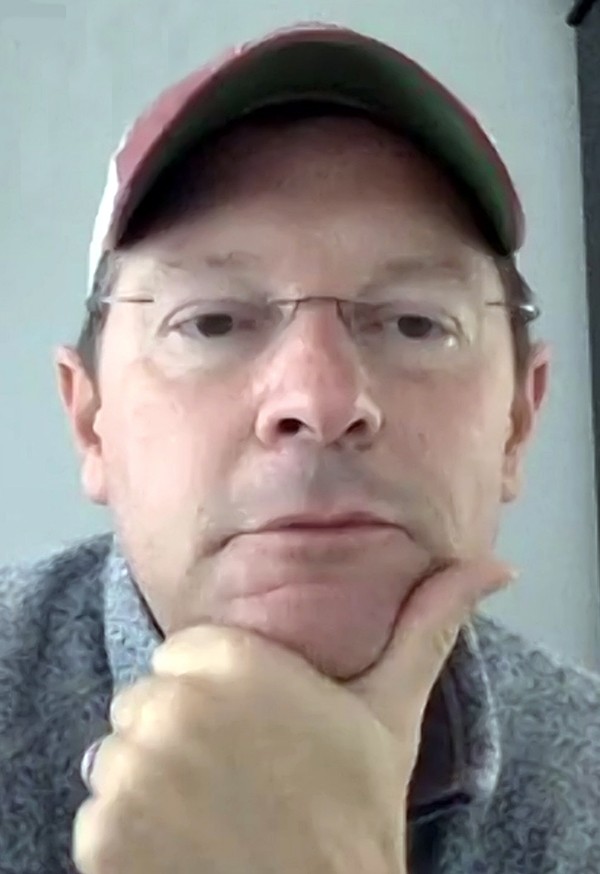

Asking people to “do that right thing” clearly did not work particularly well in Shelby County over the past few weeks. David Sweat, the health department’s Chief of Epidemiology, says his office was able to track a “sort of normal pattern of people’s behaviors” from March to mid-November. But all bets were off with the three “super spreader events” of Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve.

“That’s three waves of a behavior change in a population that have a tendency to supercharge the epidemic,” Sweat says. “The impact of that may make it harder to see the impact of a vaccine because we’re not in a normal [virus] distribution pattern right now.”

Normal won’t happen, Sweat says, until 70 percent of the county’s population — or 655,000 people — can be vaccinated. With the current vaccine supply, getting there could take a year. Before then, though, we could see the impact of the vaccine in decreasing case or transmission rates. Sweat says he’s not sure how many people would need to be vaccinated before we could come to that tipping point.

But Sweat hopes prioritizing healthcare workers, nursing home residents, and vulnerable populations (like the elderly and those with underlying health conditions) will begin to bend down the county’s death rate. “That is absolutely the purpose of targeting and prioritizing those folks,” he says. “There is a lot of evidence that if people — even if they aren’t in those groups — do get COVID and they’ve been vaccinated, that their illness is far less severe, they’re much less likely to go to the hospital, and [the virus is] much less likely to kill them.”

And that’s a start. That’s where we are. The bottom line is that the vaccine may be the only thing that will ultimately begin to move Shelby County through the dark tunnel toward the light of normalcy. How fast we get there is still the big question.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks