In August, 2016, Tennessee Democratic Party chair Mary Mancini announced that the state party executive committee had voted to disband the Shelby County Democratic Party, a hopelessly fractious organization that, as Mancini noted, had experienced “many years of dysfunction.”

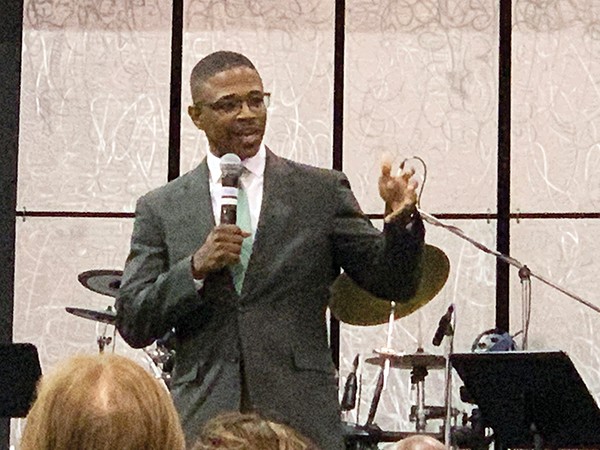

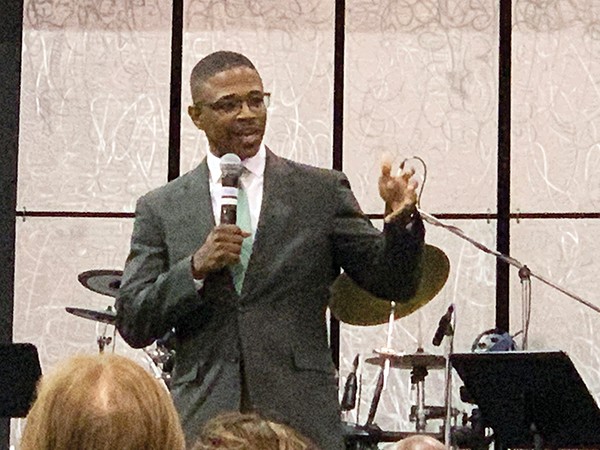

One year later, in August 2017, a reconstituted local party took shape at a convention that crowned months of focus-group activity in tandem with the state party. Corey Strong, a Shelby County Schools administrator and a military reservist, was elected chair of a new body that possessed both an executive committee and a larger “grassroots” council.

Coupled with the revived Democratic activism that, in Memphis as elsewhere, fueled a “resistance” movement to President Donald Trump, the moment looked promising indeed for local Democrats.

But now, a year and a half later, in the aftermath of party successes at the ballot box in 2018 and on the threshold of a presidential election year, the Shelby County Democratic Party is freshly riven by a dispute that seemingly has racial overtones but may actually be the consequence of warring ambitions and an internal power struggle.

Months ago, Strong had indicated that he would not seek re-election, and for a long time only one potential successor made his leadership desires public. This was Jeff Etheridge, a retired businessman (Dilday’s TV Sales and Service) and an activist who had pulled his oar in many a party drive and political campaign.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Michael Harris for the (self-)defense.

Etheridge’s home base was the Germantown Democratic Club, a racially diverse organization whose membership encompassed large sectors of Shelby County well beyond the enclaves of East Memphis and the county’s eastern suburbs. More than most Democratic groups, it had been responsible for organizing the Shelby County party effort, from the reactivation effort onward. Its president, David Cambron, had, with his wife Diane and other core members, taken the lead in making sure the party had a full roster of candidates in the 2018 election.

But there were other party power centers, as well. One of them was the Young Democrats of Shelby County, a group that tilted more toward the urban precincts of Midtown and the inner city. Its president, Danielle Inez, had been Lee Harris‘ campaign manager during Harris’ successful 2018 campaign for Shelby County mayor, and she had become his primary assistant in the reconstituted county government, someone hugely influential in staffing and logistical decisions.

Inez and the YDs were also feeling their oats and looking to make further contributions. They cast about for one of their own to bear the hopes of the younger generation for party leadership, and — for reasons best known to them — settled on one Michael Harris, a young man who had taken an active role in party outreach activities.

Those were the two known candidates when the party met Saturday before last at White Station High School to hold its preliminary caucuses for the convention to be held this past Saturday. In the nomination process other names were put forward — Erica Sugarmon and Allan Creasy, two impressive candidates from the blue wave year of 2018 — but these nominees withdrew, leaving only Etheridge and Harris.

There matters stood until the beginning of last week, when Etheridge began communicating with party leaders, complaining of “pressures” and stress he was getting from backers of Harris — some of it, he indicated, with racial overtones (Etheridge is white, Harris black). He had meant to be a unifying force, not a divisive one, he told his auditors, and he saw his opportunity to build bridges being undermined by a whisper campaign.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Harris supporter Danielle Inez and nay-voter David Upton muse over the outcome.

Simultaneously, word was getting out about difficulties Harris had experienced as a young and inexperienced lawyer.

As it turned out, there was evidence on the public record that in June 2017 Harris had been suspended for five years from his legal practice by the Board of Professional Responsibility of the Supreme Court of Tennessee. He was accused by the board of “lack of diligence and communication, excessive fees, improper termination, failure to expedite litigation, failure to perform services for which he was paid, unauthorized practice of law, dishonesty, and conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice.”

As a precondition to consideration of listing his suspension, the board ordered Harris to “make restitution” in the total amount of $22,975 to nine clients whose cases he was considered to have mishandled.

Knowledge of these facts emerged more or less at the same time that word of Etheridge’s withdrawal was getting out. On Wednesday of last week, which was the formal deadline for any post-caucus applications of candidacy, news was put out that two Memphis state representatives, London Lamar and Raumesh Akbari, had filed petitions to run for local party chair. Both were well-regarded young African Americans, seen as scandal-free legislative stars with wide appeal to all segments of the party.

Later Wednesday, stories were hitting the state media to the effect that Lamar had become the consensus choice. In actual fact, both she and Akbari had been desperation hotbox choices and would end up declining to pursue the chairmanship, pleading the press of business in Nashville. That objection was on the level, as anyone who has seen the demanding legislative process at first-hand can attest, but the swirls of internal discontent in Shelby County party circles had become all too obvious by now and were clearly another factor.

During the brief period when Lamar’s name was being floated as a consensus choice, Harris was confronted by party elders (former chairman David Cocke and Shelby County Commission chair Van Turner among them) who suggested that he yield the chairmanship to Lamar, thereby saving himself and the party the obvious public embarrassment that would come at Republican hands when his background was publicly vetted, as inevitably it would be.

In appreciation of his own efforts and ambition, Harris, now working as a compliance officer for Advance Primary Care, might serve for a year as a party vice chair, using that interval to make amends for his legal derelictions and refurbish his personal credentials. Harris said he’d think about it. He thought about it, said no, and meanwhile so did Lamar and Akbari.

That was the background of events going into Saturday’s party convention at Lindenwood Christian Church. As an ironic complement to the confusion, the party had agreed weeks earlier to conduct the chairmanship vote by the process of Ranked Choice Voting, a method of resolving multi-candidate races by reassigning the votes of trailing candidates in subsequent rounds of recalculation.

Given the fact of there being only one candidate (Harris), it was hard to see how the method of RCV could be applied, but Aaron Fowles, a local adherent of the process, provided a methodology which was announced to the voting membership by outgoing chairman Strong. Inasmuch as RCV (also known as IRV, for “instant runoff voting”) required that a winner ultimately receive 50 percent of the vote “plus one,” Harris, as the sole nominee, would be matched against votes for “none of the above.”

Should Harris be outvoted by that formulation, it was agreed beforehand, Strong would continue to serve as party chairman until a new convention (hopefully, one with multiple candidates) could be held.

Those were the circumstances when what seemed an artificially relaxed buffet feed was concluded, and the delegates elected a week earlier at White Station filed into the church sanctuary, accompanied by a fair number of curious onlookers.

Harris had arrived late and had worked the crowd. Now it was his time to take the stage and face the voters and the accusations that hung over him.

He began with the device that might have been expected. “Those of you who have never made a mistake, raise your hands,” he asked. Unsurprisingly, there were no takers. He then went on to give a brief bio of his life, admitting at this point, without specifying, that he had made his share of mistakes, and exhorting his audience to think in terms of unity. “We shouldn’t be turning on each other,” he said. “We should be turning up the heat on the Republicans.”

Harris said he took responsibility for his actions and cited his generally creditable past performance as vice chair of the party’s outreach efforts. Still, he faced questions. How many elections had he voted in, he was asked. He could not recall in any detail, but said, “I’m an active voter now.” Inevitably, the questions came about his legal issues.

Asked how much money was still owed to the past clients, Harris was vague on the amount and slow to acknowledge that much, perhaps most, of what had been dispensed was paid out by the Tennessee Lawyers Fund for Client Protection or other legal-support organizations. The bottom line: He would still need to compensate the organizations that made the payments.

“I am not a thief!” Harris insisted, despite the fact that misappropriations of his clients’ money was one of the prime allegations against him.

“He has paid his dues,” said supporter George Boyington. Inez praised Harris’ “courage” and what she considered the deftness of his responses, though others, like Danielle Schoenbaum, one of the party’s corps of surprisingly effective suburban legislative candidates in 2018, didn’t think as highly of them: “2020 is very important,” Schoenbaum said. “If you put self first, before party, you’re not fit to be chair.” It was a theme expressed by others, as well.

And there was the matter of the detailed evidence against Harris. One speaker noted that people had been foreclosed on and lost their homes because of his ineffective or even nonexistent representation.

Inevitably, in days to come, pages from the case reports against Harris would surface. As one summary said, “Mr. Harris repeatedly took money but did not provide the most basic of services. He took desperate clients, who came to him as a last hope, and did nothing for them. It is not that he took difficult clients and fought the good fight but lost. He took people’s money and did not complete the most basic of tasks. He did not respond to basic discovery requests or summary judgments (ever). He literally did not fight at all.”

Interestingly, given the job to which Harris was aspiring, that of leader and figurehead of one of the county’s two major political parties, the opposing lawyer in several of the cases for which Harris was cited by the Board of Professional Responsibility was one Lang Wiseman, a former county Republican chairman and current deputy governor of Tennessee. This fact underscores the truism that none of Michael Harris’ legal misadventures are unlikely to remain unknown in the public circles he will inhabit as a party chair.

And a party chair he is, as of Saturday. Of the 76 eligible Democratic voters present, 72 actually cast ballots, and Michael Harris received 37 of those votes, versus 35 for “none of the above.” He had received precisely 50 percent plus one — the bare minimum needed for election.

Harris’ supporters are optimistic that he can unify his party and lead it to a victorious election year in 2020. His detractors fear the worst, a public catastrophe and implosions yet to be imagined. And the state party, having interceded so dramatically in 2016, is not in the best position to do so again.

Chairman Harris and his executive committee will be meeting again soon to determine who the rest of the party’s officers will be. That’s the next round of decisions that will loom large in the Shelby County Democratic Party’s future.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  NBC

NBC  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  bbbskw.org

bbbskw.org  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  JB

JB