Yvonne Mitchell had to be patient when her father, producer Willie Mitchell, was at work. Since she’d turned 18, she’d been working at Royal Studios, where all of Hi Records’ output was recorded. “He’d be working in the control room, and I would be in my office. Then I’d go back to help him when he needed me during recording and mixing sessions,” she recalls. But this day was different. She hadn’t heard from Willie for a while.

Wandering back to the control room, she saw Willie seated at the mixing board. A voice echoed through the speakers, “I can still feel the breeze …” as eerie tremolo strings shivered with cinematic urgency. “That rustles through the trees …” An organ chord suddenly chopped the silence like a pang of loneliness. And then Yvonne saw her father’s face. He was in tears.

“He had to piece so many parts together for that song,” Yvonne recalls. “He would take it apart, then stop and start tearing up. That particular song took him a whole day to mix. I said, ‘Dad, why are you crying?’ He just looked at me and said, ‘This is a masterpiece.’”

He wasn’t wrong. Half a century later, hearing Al Green sing “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?” can still give you goose bumps. It’s a different beast than the Bee Gees’ original version. The intimacy of Green’s voice, the sacred steps of the Hi Rhythm Section playing behind him, those strings, and other sonic surprises all carry the listener on a twilit journey. It was a breakthrough moment in the history of soul music, or any music.

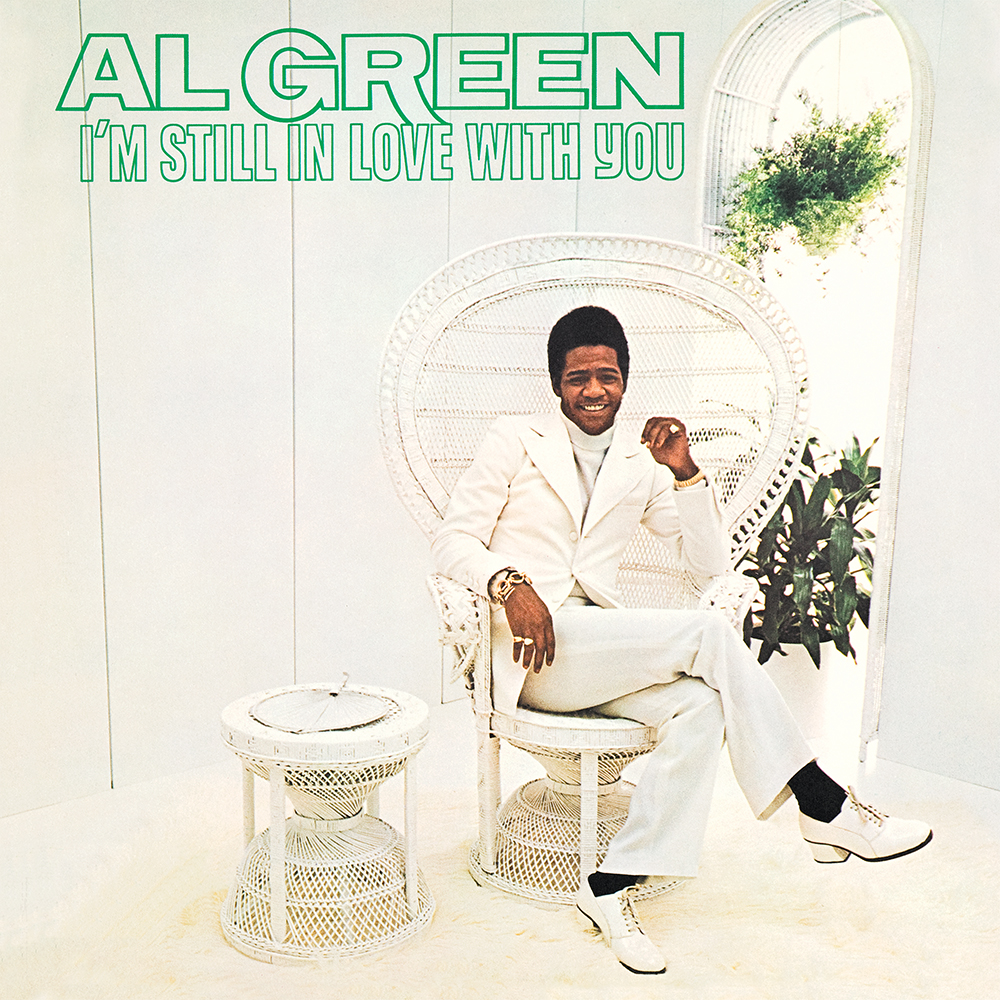

Yet the track was but one of many breakthroughs, both personal and artistic, that were going down then in the former little cinema known as Royal Studios, one of the oldest continuously operating recording facilities in the world to this day. Fifty years on, it’s worth revisiting those months, starting in late 1971, during which Hi Records became the epicenter of the musical universe, culminating in Al Green’s twin masterpieces of 1972: January’s Let’s Stay Together and October’s I’m Still in Love With You.

A Long Time Coming

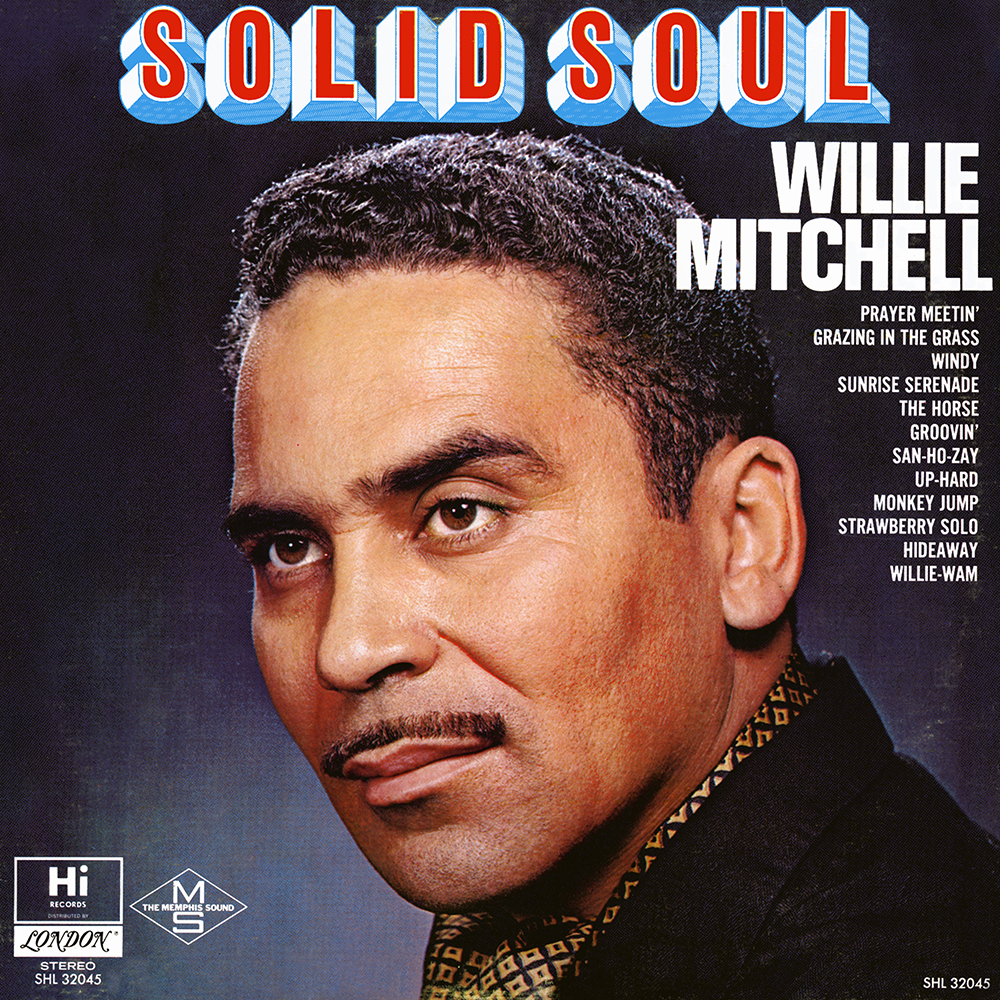

For Willie Mitchell, it had been a long time coming, marking the culmination of many years’ worth of craftsmanship as he toiled to create a distinctive sound. What he arrived at, with tracks that flowed with watery chords underpinned by an inexorable rhythm section and topped with Green’s silky delivery, sounded like nothing else on the pop landscape at the time.

Willie’s grandson Boo Mitchell, whom he raised as his own son, recalls the trajectory that took the trumpet-wielding Willie, aka Pop, to the apex of the 1970s hit parade. “Pop came from the big band era,” says Boo. “But when Pop got back from the Korean War in ’55, he was tired of big band. He wanted something different. So he started a band with [drummer] Al Jackson Jr. and his younger brother [and baritone saxophonist] James. That grew into the Memphis soul sound.” It was a new brand of stripped-down, hard-hitting, groovy R&B, ultimately popularized globally when Jackson and others began recording at Stax Records, and it had its roots in Willie’s outfit. “He had the most famous band in town,” Boo says. “Everybody played with him at some point.”

James would later play a major role in the classic Al Green oeuvre. But it all began when Willie was hired by Hi Records in the early ’60s, with the brothers’ horn sound propelling several instrumental singles for the label, including the hit “20-75” in 1964. That track was the first where Willie had complete control of the production, a giant leap forward in more ways than one.

“Pop went through all of this racial oppression to get to where he was,” Boo explains. “The engineer that was at Royal in the early ’60s, Ray Harris, told him that Black people couldn’t touch the mixing board.” Both the injustice and the aesthetics of it rankled Mitchell, so he threatened to quit unless he could engineer his own productions. “The first song Pop engineered was ‘20-75,’” says Boo, “and you can hear the difference: The music just jumps out of the speakers. So he spent the next several years perfecting the sound of the room. And after he finally bought Ray Harris out in 1968, he was the lead engineer, full-time. That’s when he really got the room the way he wanted it.”

Hi Rhythm

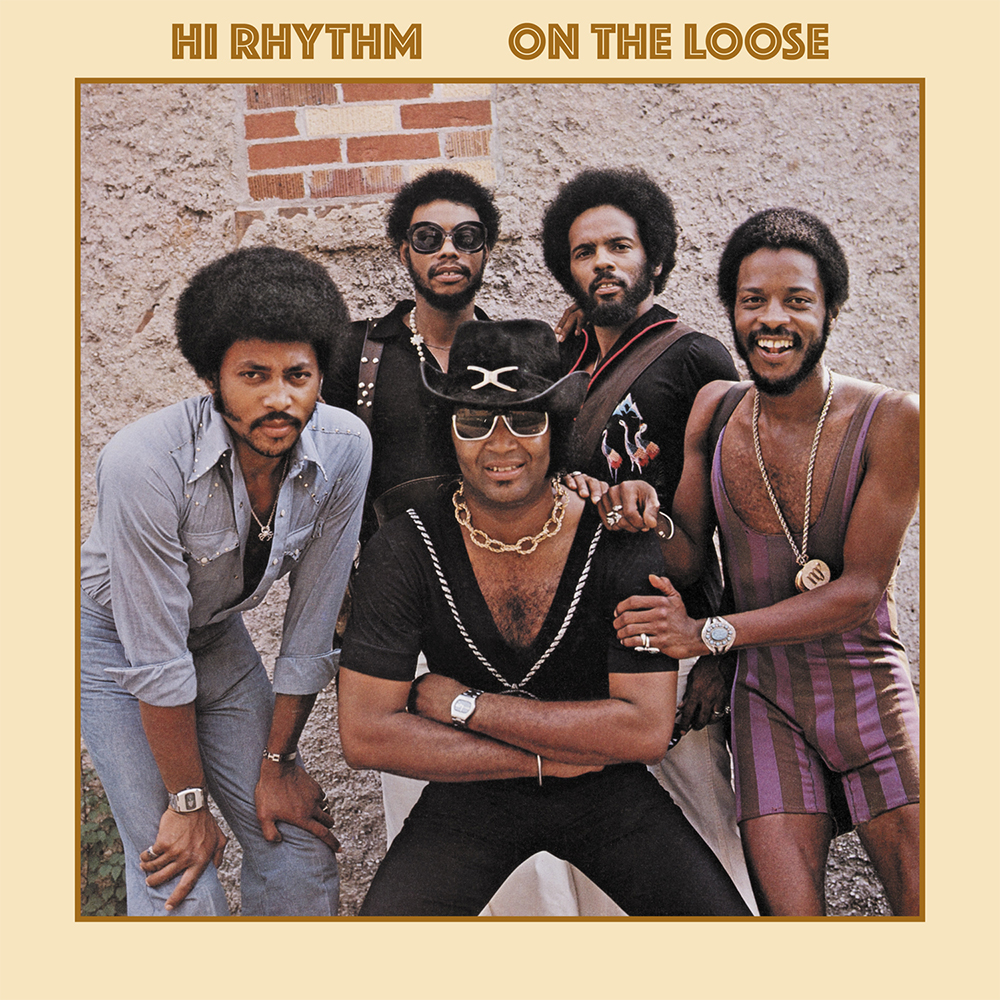

Bit by bit, he was coming closer to realizing the sounds in his head. His sonic perfectionism paid off with more instrumental hits on Hi, made all the more compelling by the house band he assembled. By the mid-’60s, Willie’s stepsons, Horace and Archie “Hubbie” Turner, were playing in an R&B band called the Impalas with two brothers, Mabon “Teenie” Hodges on guitar and Leroy “Flick” Hodges on bass. Willie brought them in to his sessions at Royal, starting with Flick.

Speaking from the studio’s tracking room floor today, Flick points to where he stood. “Right here. I was 17 years old. I’d never done a recording in my life. And I was right here with Al Jackson Jr., Joe Hall, James Mitchell, Willie, and Reggie Young. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing!”

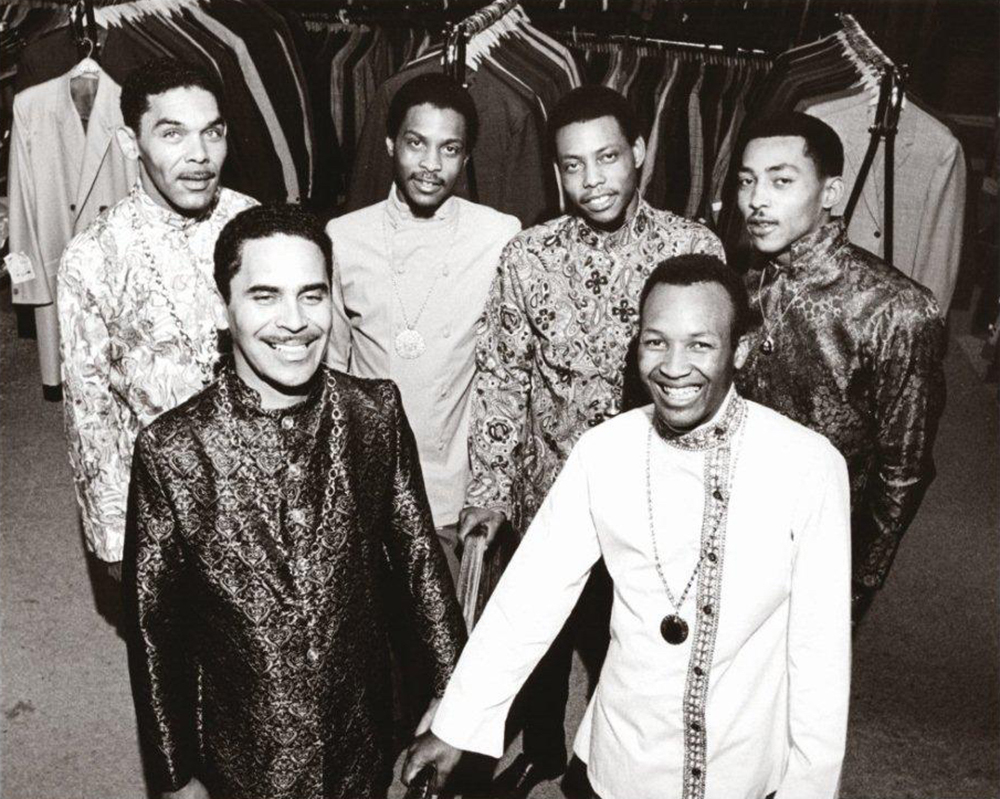

The compelling grooves of Mitchell’s solo records argue otherwise, especially after Willie assembled a new house band derived from the Impalas. By 1968, the Hi Rhythm Section boasted a young Howard Grimes on drums, who had played on early Stax hits and whose beat was so insistent that Willie dubbed him “Bulldog.” Teenie joined on guitar and Hubbie on keyboards, and the band took on a chemistry all its own.

When Hubbie was drafted and left for Vietnam, another Hodges brother, Charles, stepped in on keys and the group carried on both in the studio and on the road. And, as Flick notes today, that time together was key. “The five of us worked together every weekend. We really knew one another.”

To this day, as Charles Hodges notes, “We are as one. And there are not many musicians that can say that. You just feel each other.” One of their early successes, a cover of King Curtis’ “Soul Serenade,” led them to tour the country. In Texas, they met one Al Greene, a soul crooner struggling in the business with one modestly successful single, and Willie invited him to record for Hi in Memphis.

Wisely having dropped the “e” from his surname, Al Green was getting closer to the stardom Willie imagined for him, but he had an unremarkable start on Hi. “Al Green’s first record, Green Is Blues, didn’t sell anything,” Boo Mitchell notes. But as Willie and the band worked with Green, the producer was working toward a new goal: breaking away from the instrumental hits and reinventing the Memphis sound again.

Listen to the Room

Willie’s daughter Yvonne remembers that time well. “He wanted a new sound,” she says. “When I would drive him to the studio, we couldn’t play the radio. He’d say, ‘Would you please turn the music off?’ He said, ‘People steal from me, I don’t steal from them.’”

Once they were at Royal, he put the acoustics of the space under a microscope. “It took him almost two or three years to find his sound,” says Yvonne. “He’d be buying burlap and putting all this stuff on the walls. Then he would just sit here in the middle of the floor, beating on a snare drum. He’d say, ‘No it’s not right’ and beat on the snare drum some more. Finally he said, ‘I got it! I got it! Come listen to the room!’ I said, ‘Listen to the room?’”

The sound of that room colors Green’s second album, Al Green Gets Next to You. The LP took a quantum leap musically as well, chiefly in perfecting the simmering, slow funk of the rhythm section. With slamming tracks like “I Can’t Get Next to You,” “I’m a Ram,” and “Right Now, Right Now,” Green’s naturally silky voice turns on a dime to growls and shouts. But the singer insisted that his original, the more pensive “Tired of Being Alone,” was the hit, and, after lingering low in the charts for months, this proved true.

As Boo says, “Al Green Gets Next to You was right before Pop perfected the room. And then he gets to ‘Tired of Being Alone,’ and that’s more like the Al Green sound that you’re used to.” To Boo, this expresses Willie’s drive to reinvent himself. “See, people kept jacking his sound. He basically invented the Memphis soul sound in the ’50s, before anybody. So at the height of soul music, he was like, ‘Okay, everybody’s doing what I did. Let me change my sound again.’ So he started making his stuff with Al a little more sophisticated.”

Soul music was getting more sophisticated everywhere at the time, but where some artists, like Isaac Hayes, took their jazz influences in a more orchestral direction, Willie Mitchell combined sophistication with the intimacy that came from “listening to the room.” When “Tired of Being Alone” finally clicked in the charts, just when Hi Records co-owner Joe Cuoghi died and left his company shares to Mitchell, the producer was encouraged on all fronts to go with his instincts. The next Al Green single, released in November 1971, embodied that.

“This Could Be Something”

As Willie himself says in Robert Mugge’s documentary, Gospel According to Al Green, “The style came about because Al was singing; he was really singing hard. I used to tell Al, ‘You need to soften up some.’ … I said, ‘Al, you’ve got a good falsetto. You need to settle this music down.’ All my life, I’d tampered in jazz chords, and I began to write some jazz chords, trying to get another sound for Al. Finally one Saturday afternoon, I was tampering around on the piano, and I came up with this melody of ‘Let’s Stay Together.’ And I said, ‘This could be something.’”

At the same time, the final pieces of the recording puzzle fell into place for the producer. “Let’s Stay Together was the album where he perfected everything,” says Boo. “He perfected Al on microphone #9. That’s why that album sounds different from Al Green Gets Next to You. It has a smoother, more deliberate sonic tone to it. Every record after that had that smooth, silky sound, like Al Green is in your living room.”

The singer’s delivery went hand in hand with the production. “Really, ‘Let’s Stay Together,’ the song, was where Al discovered himself,” says Boo. “[Al and Willie] had a big fight about getting the vocals to that song. Al was singing hard like the other soul singers at the time. And Pop was like, ‘No, I want Al Green.’ And Al said, ‘Well I don’t know who that is.’ And he left! But when he came back, Al said, ‘Well I’m just not gonna try at all.’ And that ended up being the sound.”

Yet, beyond Willie Mitchell’s painstaking craftsmanship, another facet of the Hi sound from 1972 onward was the producer’s openness to the unpredictable. That, too, was captured in the single that started it all. “We put the track down, and that’s when everything happened,” Willie explains in the film. “We are in the ghetto area, and there’s a bunch of winos out there, and they were all out there drinking. So Al said, ‘Why don’t you go and get four or five gallons of wine, let’s bring these people into the studio.’ So we brought about 50 people in here. All the winos were drinking wine, laying on the floor when we cut the record. And we’d all tell ’em to be quiet.” Careful listening still reveals the guests who were present that day.

Perfect Imperfection

The loose atmosphere extends to the band itself. Indeed, the Hi Rhythm Section, who still records as a unit today despite the deaths of Al Jackson Jr., Teenie Hodges, and Howard Grimes, brings a magic to Let’s Stay Together, I’m Still in Love With You, and subsequent albums that transcends even Willie Mitchell’s vision. And that’s just how Willie wanted it.

As Hubbie puts it, “Willie was kind of like Miles Davis, when Miles got his [mid-’60s] group together, with Herbie Hancock and those guys. They were really young when Miles got them. Willie was the same way. Like an older guy with the young guys. ‘You guys do you guys. Do what you do.’ He’d let you go ahead and do it. Be creative.”

Speaking of his dramatic organ swipe on the track that brought Willie to tears — “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?” — Charles recalls just such a creative moment. “Al was the type of singer that could lead you to a chord. I’m right there listening and I want to be on him like a duck on a june bug. So when he sang, ‘I can feel the breeze,’ I thought of a breeze in the trees. I just felt it. And I felt self-conscious about it when I heard it back. I wanted to do it again, but Willie said, ‘No, no. This is the take right here. You all can go home.’”

Ultimately, of course, Willie was always alone at the mixing console and thus had the final say. This extended even to the unique string arrangements by his brother James, more edgy string quartet than symphonic bombast, and yet another novel element introduced to the Al Green sound in 1972. As Boo reflects, “Uncle James was an absolute genius. I’ve been studying his arrangements recently, both the strings and horns, and they were so unorthodox and unpredictable. That’s why they work.” Listening to the multitracks reveals “even more there that Pop would take out on the mix. Like extra horn parts and stuff you don’t hear on the record. He just muted them. … He knew how much to take from Uncle James and how much not to take.”

Willie’s exacting approach to mixing meant he always did it on his own, right there at Royal. It was partly a point of pride. After finally being allowed to engineer himself in the ’60s, then ascending to partial ownership of Royal and Hi, he’d personally pieced together the gear with the same ear for detail that had shaped his acoustic room design. As Boo describes it, the studio was such an extension of Willie’s vision that working elsewhere was unthinkable. “That’s the most ridiculous idea. It never happened. It would be like Michael Jordan wearing another player’s basketball shoes.”

Instead, Willie Mitchell remained comfortably ensconced in the sonic temple of his own making, never changing his approach after perfecting it with Al Green in 1972. He made stars out of many singers through the decade, but as the flashier sounds of disco and new wave became ascendant, Hi Records’ star dimmed. Al Green, of course, made a sharp turn to gospel and is the bishop of his Full Gospel Tabernacle Church to this day. When he finally returned to Royal to work with Willie on his return to secular soul, 2003’s I Can’t Stop, sure enough, Royal was there just as it was back in the day. And since Willie’s death in 2010, Royal continues under the stewardship of the Mitchell family, with nearly all of its vintage gear intact, albeit with a few upgrades to digital capabilities as well.

Perhaps most importantly, the Hi Rhythm Section and the Mitchell family carry the torch of Willie’s philosophy, mixing spontaneity, sophistication, and simplicity. As Boo puts it, “I grew up watching him produce. There’d be a studio full of world-class musicians, and everybody’s playing their thing perfectly, and Pop would — Pzzzew! — stop the tape. And he’d be like, ‘Hey man, it’s got a false feel!’ Then they’d do it again, and even if someone hit a clam or something, he’d be like, ‘That’s the take!’ He was more concerned with the spirit and the vibe and feel of a record than the technical correctness. Talk about perfect imperfection! Pop knew when God was in the room.”

Join Alex Greene, Boo Mitchell, and Rev. Charles Hodges as they discuss the making of these classic 1972 albums at the Al Green Listening Event, Memphis Listening Lab, Saturday, March 12, 6:30-8 p.m. Free.