A crash course in historical irony was on hand last night, as my son and I trundled into the Orpheum to see Hamilton: An American Musical. While the cast of the celebrated musical sang and rapped their way through the circumstances and ideals upon which this country was founded, a shadowy Trump administration and its unelected advisor, Elon Musk, had just frozen funds for the National Endowment for Democracy in direct violation of the 1974 Impoundment Control Act (which mandates that funds appropriated by Congress be distributed to their proper recipients). Meanwhile, the United States apparently abandoned all commitments to erstwhile ally Ukraine. Authoritarian states like China and Russia were delighted by both moves. And, with characteristic hubris, Trump tweeted “LONG LIVE THE KING,” referring to himself. Welcome to another day in Upside-Down World, where a supine Republican Congress continues to give the executive branch free rein.

Meanwhile, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) diverted all funding originally targeting underserved communities only two weeks ago. Instead, those monies shall now go to projects honoring the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. That, perhaps, is the most chilling irony: the NEA celebrating a revered historical document as a kind of fetish while caving in to principles that defy its very intent.

It was not always thus. As Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda told CBS News in 2017, without the NEA he might never have had a career at all.

“My first musical was workshopped at the O’Neill Musical Theatre Center, which is partly funded by the NEA,” he said. “But that’s not even the real story. The real story is the NEA funds things in all 50 states. They are the supplement when arts programs get cut. They fund reading programs between parents and young children in Kentucky. They fund, you know, educational initiatives all over the state, all over the United States. So, when we talk about the NEA, we’re talking about a very small amount of money that does get an enormous return on its investment in terms of what it gets out of our citizens.”

How could one not imagine President Trump’s royal ambitions whenever Hamilton‘s farcical character of King George III (Justin Matthew Sargent) appeared, full of imperious condescension, the perfect foil for the musical’s American patriots? It was enough to give this audience member chills, a bracing reminder of this country’s origins.

The Orpheum has always championed Miranda’s 2015 musical, having been the first theater to bring Hamilton to Tennessee in 2019, then again in 2021. And while those touring productions were stellar, the new touring production, at the Orpheum until March 2nd, hits differently. Suddenly, it seems more necessary than ever.

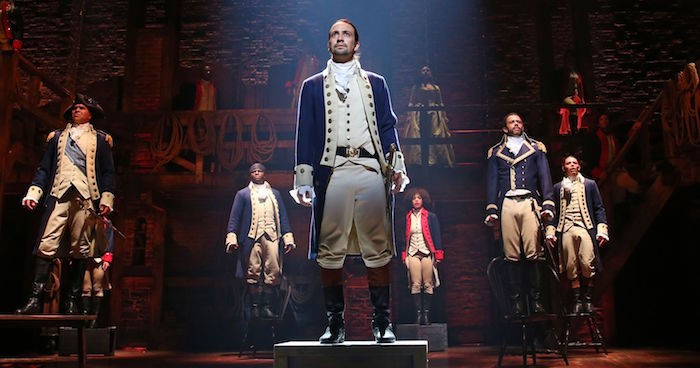

From the beginning, Hamilton was a shot across the bow for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Its central conceit was to recast the country’s white, propertied “Founding Fathers” as multi-ethnic players fired with the grit and grind of hip hop culture and the soaring emotions of an R&B ballad. And, as Miranda told the New York Times after its opening, “Our cast looks like America looks now, and that’s certainly intentional. It’s a way of pulling you into the story and allowing you to leave whatever cultural baggage you have about the founding fathers at the door.”

Indeed, the musical’s staunchly pro-immigrant ethos is a heartening reminder that Trump is not our king. This was abundantly clear last night, when, during the “Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down)” scene, after the Marquis de Lafayette (Jared Howelton) says the word “immigrants,” and Hamilton (Michael Natt) joins him in saying, “We get the job done,” there were enthusiastic cheers and whoops in the audience. Clearly, I was not the only one who’s spirits were bolstered.

Natt, as a person of color, perfectly embodied the idealism and the drive of his character, delivering the rhymes and raps — sometimes derived from actual historical texts — with understated aplomb, as did his more aggressive foil, Jimmie “JJ” Jeter as Aaron Burr. Lauren Mariasoosay, of South Asian ancestry, masterfully inhabited the unique mix of Colonial-era decorum and emotionalism of Eliza Hamilton, especially in the anguish she conveys at the show’s final moment, just before the house goes dark. And perhaps none captured the play’s inclusive spirit more than the regal A.D. Weaver as George Washington, who expressed all the gravitas that the role demands.

Washington’s repudiation of demands that he become the young nation’s new king, insisting instead on mounting an election for his successor, was a compelling beacon of hope in these dark times, when an American president dares call himself king and jokes about never needing elections again. In matter-of-factly expressing, with new urgency, what once seemed to be this nation’s imperfectly executed yet fundamental principles — a respect for diversity, the peaceful transfer of power, and the rule of law — Hamilton preserves the ideals that we’ve thus far taken for granted and offers the possibility that they haven’t been forgotten.

Back in 2016, newly elected Vice President Mike Pence attended a performance of Hamilton that caused quite a stir when Brandon Dixon, the actor playing Burr, stepped out to share some thoughts with the audience and Pence after the curtain call. If those words rang true then, they are even more critical today, as all of the first Trump administration’s excesses are amplified beyond belief. See Hamilton if you can, take your sons and daughters, and when you do, remember Dixon’s reminder to Pence:

We, sir, are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents — or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights, sir. But we truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and work on behalf of all of us. All of us.

The Orpheum

The Orpheum