Maya Smith

Maya Smith

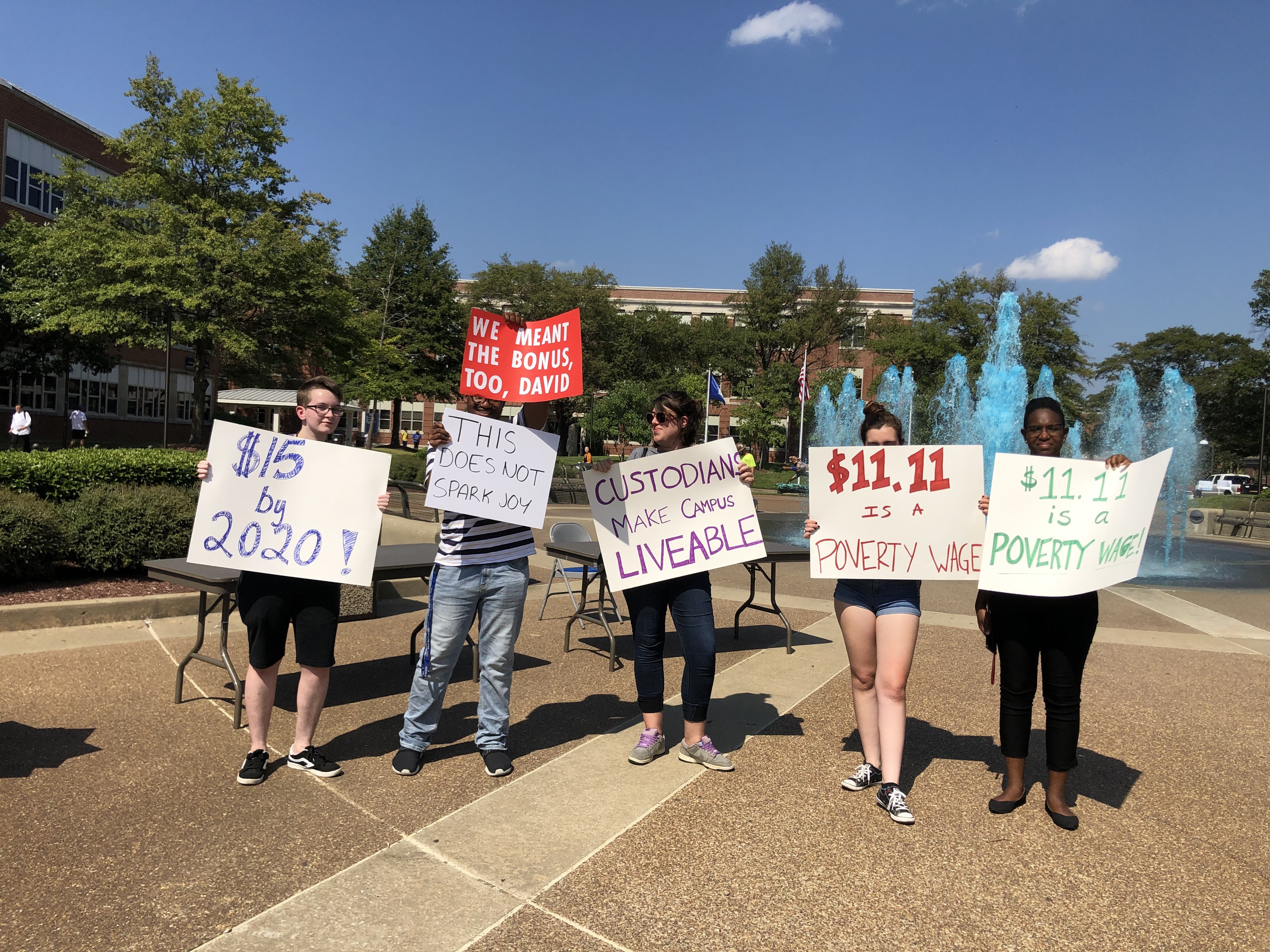

Students demand living wage for all campus workers

Students protested at the University of Memphis Friday, asking for a living wage for all campus workers and an overall more equitable campus.

The Memphis Young Democratic Socialists (901YDS), comprised of U of M students, staff, and alumni, helped organize Friday’s event.

The protest comes a day after U of M president M. David Rudd announced he would not be accepting a near $100,000 salary increase. Rudd currently earns a base salary of $394,075, according to the university.

Rudd

Rudd was expected to sign a new contract to receive $525,000 annually beginning October 1st, but said Thursday that he believes “it is in the best interest of the institution to forgo any salary increases at this time.”

“Overall institutional efficiency has been at the forefront of my agenda from the day I started, a value I firmly believe and will continue to live,” Rudd wrote.

Tre Black, co-chairman of the 901YDS, said although he is “overjoyed” with the president’s decision, “there is still much work to be done.” He noted that Rudd didn’t mention if he would still accept the near $2 million in bonuses and benefits offered by the university’s board of trustees.

At the protest, students honed in on the issue of every campus employee making a living wage of $15 dollars an hour. Rudd assured the campus in July that a plan to raise all employees’ pay to $15 an hour over the next two years was in the works, but the details of that plan were never shared.

Rudd’s promise of paying a living wage to campus workers came after Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris moved to veto $1 million in county funding going toward the university’s new natatorium until a plan to pay all university employees was presented.

[pullquote-1]

“We have a definitive plan,” Rudd said at the time. “We’ll be at $15/hour in two years. And in a sustainable manner.”

Black said that 901YDS wants all campus workers to earn a living wage, including those hired under a work-study contract, those earning a stipend, part-time and full time employees, graduate workers, and adjunct professors.

The protesters also want Rudd to participate in a public forum with 901YDS and United Campus Workers, another organizer of Friday’s action, to address these and other issues relating to “inequality and unfair treatment of a large section of students and workers.”

As an example, Black cites graduate workers not receiving health care or a living wage, yet working more than 40 hours most weeks.

According to United Campus Workers, about 330 employees on campus are paid less than $15 an hour.

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Students demand living wage for all campus workers

The group has a petition on the Action Network website. In addition to asking Rudd to forgo additional bonuses, the petition asks that Rudd reveal the university’s plan to raise campus workers’ hourly wage to $15 an hour.

The petition also notes that the groups oppose any increases in tuition and fees: “We call upon the president and the board of trustees to freeze tuition and all administrative fees, not to be increased without approval of the students.”

See the full petition here.

The university did not immediately respond to the Flyer‘s request for comment.