On Tuesday, November 20th, when the Memphis City Council began to vote on a replacement for Bill Morrison, the District 1 councilman elected on August 2nd to serve as Probate Court clerk, the racial distribution on the council effectively shifted from a 7-6 African-American majority to one, for voting purposes, of 7-5.

Hold on to that fact for a few paragraphs of background.

Though the population of District 1 is a black-majority one, voting habits have made that gap more or less marginal, and Morrison, a white educator, had little trouble winning reelection since his first win in 2007, that one stemming from a runoff victory over Stephanie Gatewood, an African-American candidate.

Given the district’s ambivalent demographic factors, it is hard to argue that a “gentleman’s-agreement” circumstance should have mandated a white-for-white replacement in the appointment process. It would be just as easy, if not easier, to suggest that District 1’s majority-black status calls for a credentialed African-American candidate to serve on an interim basis until next October’s regular election process can account for the election of someone to serve a full four-year term.

The elephant in this room is that special replacement elections on the regular November ballot, at negligible cost to taxpayers, could have been facilitated by the timely resignations of Morrison and two other council members who won elections to county positions in the August 2nd general election — District 8, Position 2 Council member Janis Fullilove, now Juvenile Court clerk, and District 6 member Edmund Ford Jr., now a member of the Shelby County Commission.

For whatever reason, all three county election victors chose to push their council incumbencies to the maximum 90-day post-election limit permitted by the city charter, thereby stifling the prospect of their replacement by constituent voters in November and making necessary an appointment process overseen by the remaining council members — already under suspicion, here and there, of tendencies toward bloc voting and collusion.

A note thereto: Current chair Berlin Boyd, an African American, has earned a reputation for siding consistently with the business-friendly, development-minded council bloc largely made up of the body’s white members.

Indeed, such votes go more toward defining Boyd’s profile than racial factors do, and he was the target of barbs from other black council members last Tuesday when he declined to add his vote, which would have been the seventh and deciding one, to the total acquired, over and over in the council’s more than 100 separate tallies, by District 1 applicant Rhonda Logan.

Lonnie Treadaway, Rhonda Logan

Consequently, Logan, president of the Raleigh Community Development Corporation and an African American, was unable to win a majority, while her main opponent, Flinn Broadcasting executive Lonnie Treadaway, a white man, topped out at a maximum of five votes from white council members and, upon occasion, one from Boyd.

And now, with a new council vote scheduled for December 4th to fill the Morrison vacancy and Fullilove’s and Ford’s as well, that 7 to 5 ratio in which Boyd’s could have been the deciding vote is no more. The new arithmetic will be 5-5, an even ratio suggesting that, if the white and black members of the council continue to vote as racial blocs (as, for all practical purposes, they did last week), they will, in theory, have an equal chance of prevailing.

The fact is, though, that two of Logan’s votes — those of Fullilove and Ford — will be gone, while all of Treadaway’s previous votes will still presumably be available, and there is no reason to suppose that his candidacy is anything but live and well.

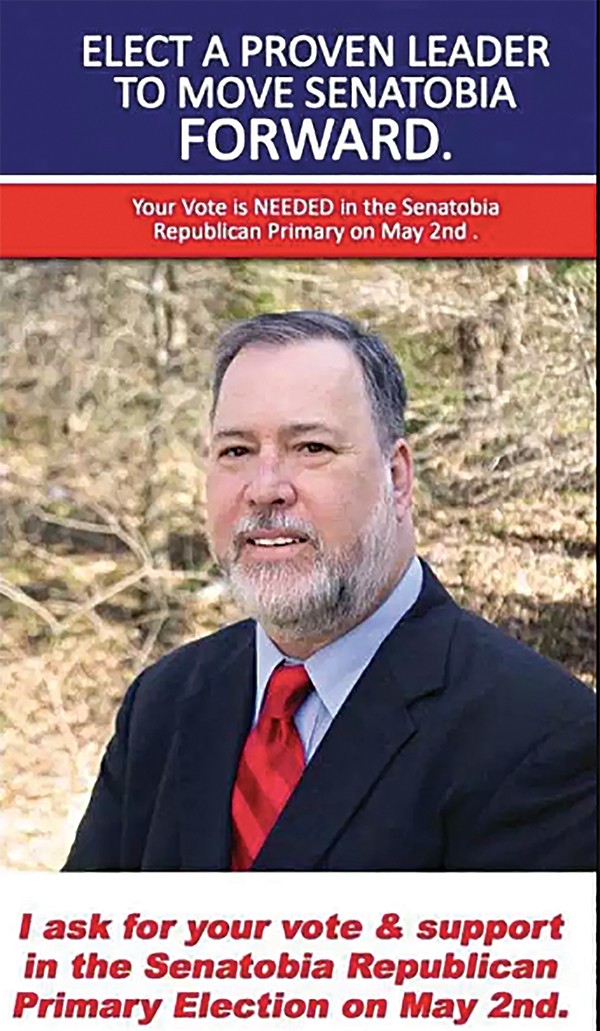

It is fair to say that eyebrows were raised by Treadaway’s bid, given the well-publicized fact that Treadaway ran for an alderman’s position last year in Senatobia, Mississippi (“a community that all would be proud to call home,” his campaign literature proclaimed, along with the statement of fact that he had lived in that city’s Ward 4 for 16 years).

It is also fair to say that a cloud of suspicion for the origin of Treadaway’s ambition immediately fell upon Flinn Broadcasting general counsel Shea Flinn, a former councilman who later became a prominent Chamber of Commerce executive and promoter of various strategies to accelerate the economic growth of the Memphis community.

Flinn makes no secret of his confidence in the abilities and sense of purpose of Treadaway, Flinn Broadcasting’s national sales manager for many years (“Yeah, I support him”) but disclaims any responsibility for his council bid.

“I’m trying to live a Christian life. I’m steering clear of politics,” protests Flinn, a family man with children who also happens to be both a political natural and a wit of some talent.

He and other supporters of Treadaway note that their man has worked in Memphis for at least 20 years, now indisputably lives in District 1, and, they say, has a keen desire to serve the community.

Much the same is proclaimed by supporters of Logan, whose website describes her as a “community developer” and quotes her as saying, “My life’s work is devoted to counseling, advocacy, & help.”

For the record, she, like Treadaway, is a transplant to District 1, having lived much of her life elsewhere, though in the city of Memphis.

There’s no law of nature saying that the contest for District 1 must be restricted to one of Treadaway versus Logan, though those were the lines that held through multiple hours of balloting last Tuesday night.

Flinn offers the thought that the balance of forces on December 4th, when the council will try again, to select representatives for three council seats, not just one, will enforce the necessity for compromise, since neither side will be able to impose its will without enticing votes from the other side.

Given the demographics of the three districts in question, the question will likely turn on whether three new African-American members will be named, creating an 8 to 5 black majority on the council, or two African Americans plus one new white member, which would keep the present ratio intact.

In the long run, meaning by next October’s city general election, the same issue will be up for resolution again. That is, if the council meanwhile is able to name anyone at all to fill the three vacancies. Some observers are already imagining scenarios emerging from the current deadlock that will result in a special called election, after all — one that the taxpayers will be on the hook for, and one that may decide whether the city is governed by an economic vanguard or anew, from the grass roots.

JB

JB