![]()

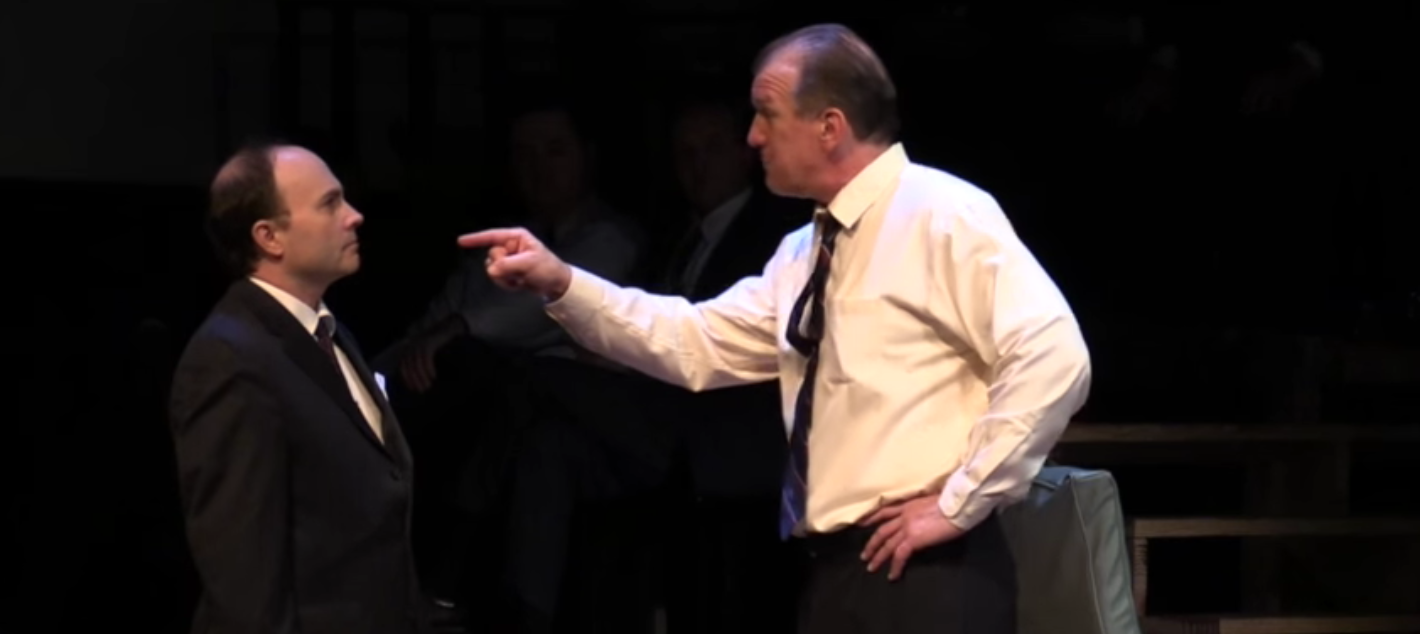

All the Way isn’t nearly as straightforward as it seems. It’s not a piece of naturalistic theater you can just stage. It’s not a musical either, but with grand themes, leitmotifs of venality and an orchestra-sized cast, this overstuffed sausage-grinder about Lyndon Johnson’s first 11-months in the White House needs to be conducted like a tense modern symphony full of explosive tragedy and punctuated by brassy squawks, and soaring metaphoric strings. If careful attention isn’t paid to the show’s desperate melodies, and ever-shifting time signatures All the Way turns bloodless, like Disney World’s Hall of Presidents without the Morgan Freeman gravitas. Playhouse on the Square has transformed the show into a fashion parade of gorgeous vintage suits, and unconvincing wigs on a pink (marbled?) set that looks for all the world like it was wrapped in prosciutto. It’s a remarkable showcase of extraordinary talent grinding its wheels in a low-stakes historical pageant. When actors as sharp as Delvyn Brown and George Dudley can’t make historically large characters like Martin Luther King and Lyndon Johnson interesting, there’s something powerfully wrong with the mix.

I’m a fan of director Stephen Hancock, but have noted occasions where concept muddled clarity. The opposite is true this time around. Kennedy’s assassination can’t be treated like melancholy Camelot nostalgia. All the Way may open with a funeral march, but it needs to be bathed in horror and bubbling over with chaos that threatens to grow worse as the play progresses. The Gulf of Tonkin incident isn’t an aside, it’s an explosion. Every provision cut from the 1964 Civil Rights bill in order to get some version of the legislation passed before the election has to bleed real blood and stink of the strangest fruit.

George Dudley is a pleasure to watch. He’s whip-smart, and even when he’s badly used the man’s a damn powerhouse. But everything is different this time around. He’s not surefooted like he usually is. Like so many of the actors in All the Way, Dudley seems unfocused, and not entirely in control of his lines. Still, you can’t act height and vertical advantages aside, he’s still the only actor in Memphis I can imagine capturing Johnson’s crude and conflicted brand of Texas idealism. And when he’s on, he’s on fire.

‘All the Way’ Comes Up Short at Playhouse on the Square

For all of its shortcomings, All the Way is something of a landmark. I can’t recall when I’ve seen such a gifted assemblage of swinging D plopped down on a single stage. With a handful of exceptions, every noteworthy Memphis actor has been called on to do his patriotic duty, and most have answered with gusto. Curtis C. Jackson and John Maness stand out as NAACP leader Roy Wilkins and FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover. Greg Boller relishes his time inside the skin of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Michael Detroit makes a sympathetic, if never entirely convincing, Hubert Humphrey and John Hemphill, Sam Weakly, and John Moore all do some fine character work. The women of the 60’are finely represented by Claire Kolheim, Irene Crist and Kim Sanders, but they are outnumbered, outgunned, out shouted, and pushed to the edge of the picture. It’s an historically appropriate dynamic, of course, but it could stand crisper translation to the stage.

Regretfully, Robert Schenkkan’s script requires more than quality acting.

All the Way is a fourth wall breaker. At the end of the show Dudley asks the audience if anybody was made to feel uncomfortable about by the things they witnessed as ideation becomes legislation, slaw, then law. He asks if we wanted to hide our faces or look away. That moment should be the key to reverse engineering an American “teaching play” that lists ever so slightly toward German Lehrstücke. It should make us want to look away. Not because of the sad black and white photographs projected on enormous screens behind the actors, but because when politicians “make the sausage” people are the meat in the grinder.

And it’s always the same people in the grinder.

There’s a frequently repeated line in All the Way about how Johnson is the most, “sympathetic president since Lincoln [to African Americans].” It’s ordinary sloganeering, of course, and an uncomfortable truth when considered from even a relatively short distance. It’s also a helpful line for considering how easily mimesis fails this kind of play where dynamic interpretation makes the difference between horrorshow and hagiography.

Face full of Johnson. Michael Detroit and George Dudley in All the Way at Playhouse on the Square.

All the Way isn’t bad, it’s worse than that. It’s boring. It’s a play that should make us see that soldiers are blown up in boardrooms not on battlefields, and how even progressive politics can play out like a slow motion lynching. It should make us flinch and look away often. But it never does.

It’s an election year, of course — in case anybody out there in Flyer-land hasn’t noticed. I suspect there’s a certain crowd caught up in the pageantry who are in the perfect mood for a three-hour reminder of the “good old” “bad old” days when even an oil-funded politician as crude and bullying as Donald Trump could dream of a “more perfect union” and get elected. Once, anyway.

Even political junkies and policy wonks may wish to spend cocktail hour chugging coffee.