The film that has had the most lasting influence on action cinema is Buster Keaton’s 1926 masterpiece The General. Inspired by an actual Civil War train chase across Tennessee and Georgia, The General contains some of the most incredible stunts ever performed for film — all of them done by Keaton himself.

There’s a straight line between The General and Raiders of the Lost Ark, the 1981 Steven Spielberg/George Lucas collaboration that perfected the kinetic filmmaking style the two friends had been groping towards with Star Wars, Jaws, and 1941. Their not-so-secret weapon was Harrison Ford, who didn’t quite do all of his own stunts like Keaton, but who still did a lot more stuff than Lucasfilm’s insurers were comfortable with.

When Disney bought Lucasfilm in 2012, the rights to Indiana Jones came with it, and soon after the House of Mouse pointed out that Spielberg, Lucas, and Ford had signed a five-film deal in 1979. That meant that even after the classic 80s run of Raiders, Temple of Doom, and The Last Crusade, and 2008’s much-maligned Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, they were owed one more. Thus was born Indiana Jones and the Contractual Obligation, aka Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

Spielberg and Lucas fulfilled their contractual obligations by executive producing this go-round, handing off directorial duties to James Mangold, and a script cobbled together from years of false starts.

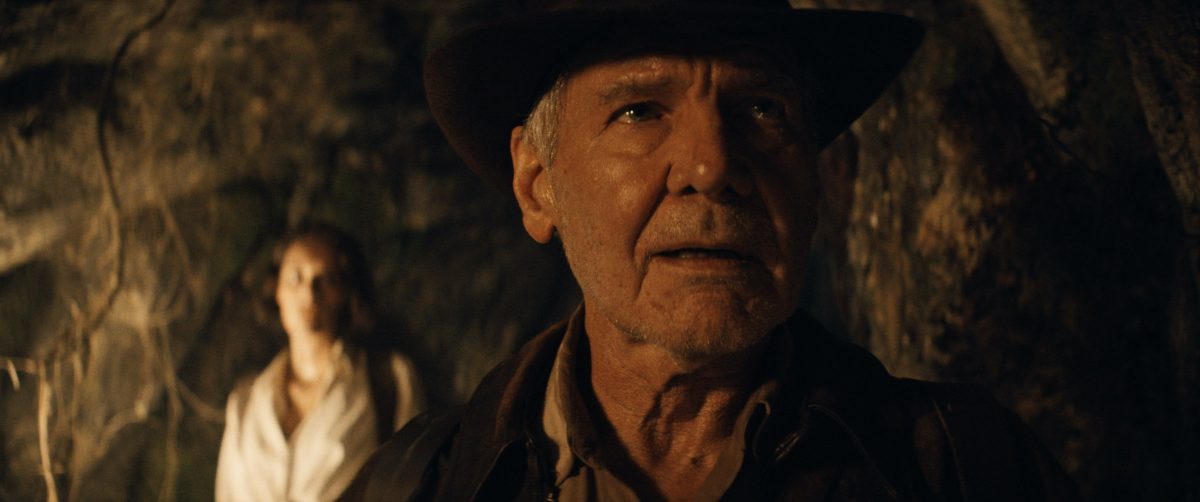

But without Ford, there’s no Indy. Any doubts that the 80-year-old Ford could still wear the fedora are quickly dispelled in The Dial of Destiny. When the action opens, Ford gets ILM’s patented de-aging treatment. It’s 1945, and the Third Reich is falling. Indy and his Oxford archeologist colleague Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) try to sneak into a German castle where Nazis are hoarding looted treasures. They’re looking for the Lance of Longious, the Roman spear that pierced Christ’s side, but in the ensuing fracas, Indy half-accidentally comes into possession of the Antikythera, half of a mysterious clockwork artifact from ancient Greece allegedly created by Archimedes.

Mangold’s assignment is to imitate the master, and the opening chase sequence, which pays homage to The General, is prime Spielbergian thrill-ride cinema. Then we flash forward to 1969, where a depressed, aging Indy is just trying to get some peace and quiet in his Brooklyn apartment. The script gets the old man jokes out of the way early, when Indy takes a baseball bat to hush up the hippies downstairs, who were blasting “Magical Mystery Tour” way too loud. The hippies are in a celebratory mood, because it’s the day of the ticker-tape parade for the Apollo 11 astronauts. It’s also retirement day for Indy, who has fallen from Princeton to a tiny liberal arts college. I guess it’s hard to get tenure when you’re a globe-trotting adventurer. His son with Marion, Mutt, has died in Vietnam, and the couple have split, leaving Indy with memories and whiskey.

Ford, who has phoned in performances in his time, comes alive in a scene where Indy tries to teach his class of bored, stoned co-eds about Archimedes. One student who is listening is Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), who reveals herself to Indy as the daughter of Basil, and his goddaughter. Helena is in the family business, but her brand of archeology is closer to Indy’s mercenary Temple of Doom approach than the guy who exclaimed “It belongs in a museum!” She wants to know what happened to the Antikythera all those years ago. Also interested in the subject is Jurgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen), a former Nazi turned NASA rocket scientist, who believes the Antikythera holds the key to time travel. Indy’s retirement is upended by a three-way chase through the streets and subways of New York, as the ticker-tape parade is in progress.

Mangold takes a lot of big swings, and most of them connect. Waller-Bridge proves a much better foil for Ford than Shia LaBeouf was in Crystal Skull. There are some great sentimental cameos, but they’re handled deftly enough that it doesn’t become a nonstop nostalgia party.

Best of all is Ford, who doesn’t treat this as a victory lap. His joints are stiffer, but when he says he’s been shot nine times, you believe him. It’s a great joy to see anti-fascist icon Indiana Jones still out there punching Nazis. We need him now more than ever.