Tara Stringfellow was born a poet.

She realized this at the age of 3 when her father read her Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” one night instead of a bedtime story. “I was instantly in love,” she says. “I thought it was the best thing I’d ever heard. It felt like almost like hip-hop, because it was a rap. It rhymed. … I asked him to read it again. I was so in love with it, and he did. I stopped him, and I said, ‘This is what I’m meant to do.’ I said, ‘I’m going to be a great American poet, like whoever this guy is’. And he said, ‘Okay, well then you’ll have to be three times as good because you’re Black, you’re a woman, and you were born into a country built to enslave you.’

“So I always knew that it would be a harder road for me as a Black American woman to get anything published, for anyone to even listen to me, let alone the biggest publishing house in the world. This country does not treat even Black little girls as if they’re worth much. I knew the road ahead of me would be a long and arduous one, and I might not make it.”

Yet she, arguably, has made it. Her debut novel Memphis, released in April of 2022, was a national bestseller and a Read With Jenna Book Club Pick. All the bookstores in Memphis carried her book. “Local businesses have made me who I am, put me on the map,” the writer says. “Women in Memphis found my book, especially Black women in Memphis. They have put me on a map.

“To break out into this industry has been a godsend,” Stringfellow adds. “I don’t think it’s just talent and hard work. This world does not give that many opportunities to unpublished people of color, so I’ve been very lucky. It’s nothing short of a miracle. I just wish there were more opportunities for writers and authors of color to be more widely read in this nation.”

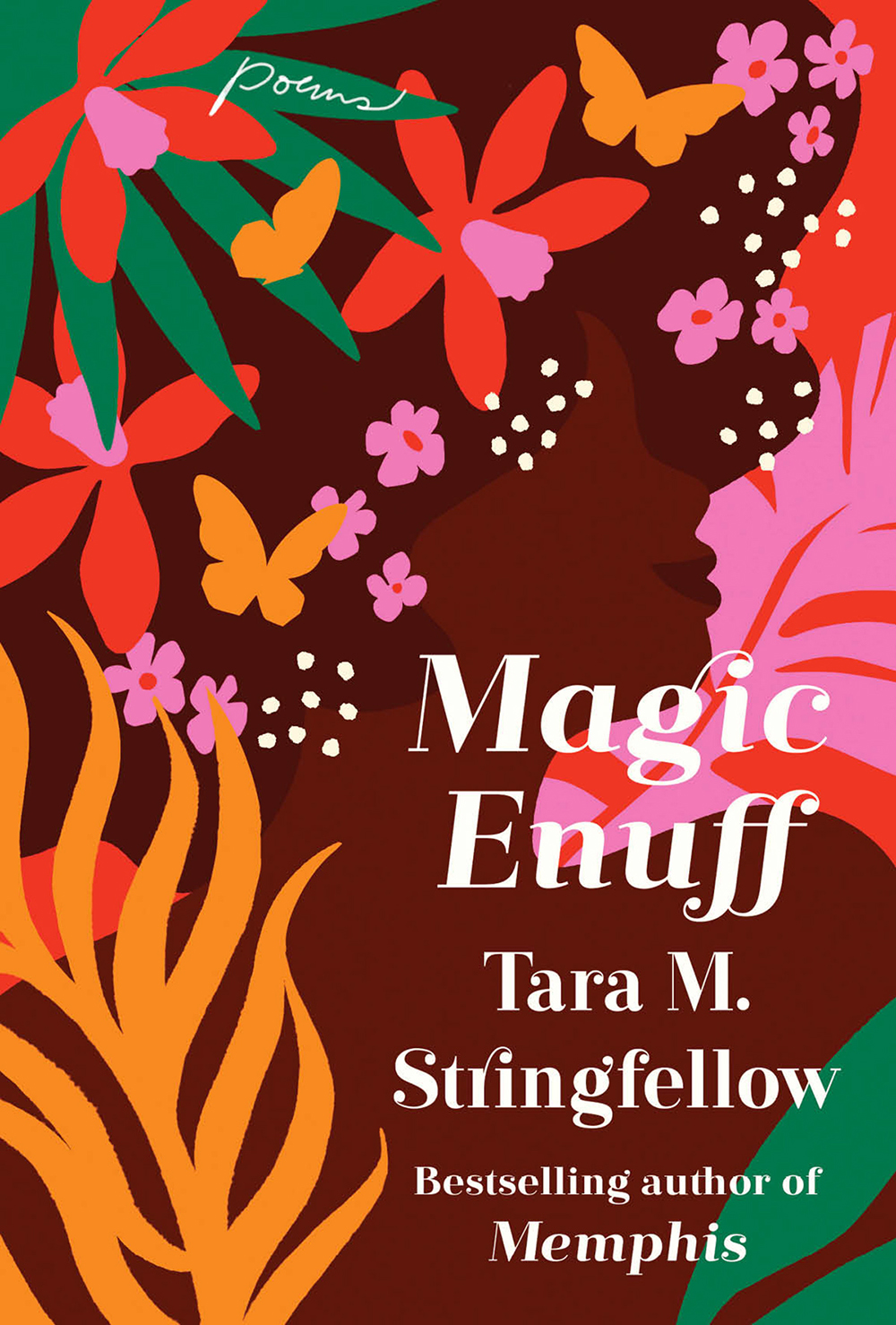

This isn’t anything new, of course. Only 250 years ago Phillis Wheatley could not get her poetry published in the U.S., a fact upon which Stringfellow reflects after the June release her collection of poetry Magic Enuff (The Dial Press). “It’s a huge historical achievement, I think, for the literary canon,” she says. “I’m very humbled.”

Poetry, after all, is some of the oldest literature we have — think of Homer, Sappho, Vergil. These are the works we’ve labeled as “classics.” “[Poetry] is, to me, the highest form of literary work,” Stringfellow says. “I think poetry is revolutionary. I think it has the ability to reshape nations. … In a novel, you have a whole chapter to get your point across — I’m not knocking novelists, and novels, I love them. I’m in the middle of a novel — but in a poem, you have not even a page to get your point across. You might only have a line or not even a whole word, a syllable.”

The verses might be fleeting, but their impacts are all the more striking, the smallest detail becoming a powerful source of imagery. In Magic Enuff, Stringfellow’s poems are deeply personal. “These were written from my experiences over the years. The narrative voice and the poetry is often just my voice. Some of these poems have taken a long, long time to come to light. This collection is my life’s work. My art speaks for herself, and she speaks loud and clear and proudly.”

There are vulnerable moments within the pages, moments where she talks about her dad leaving her mom and her own divorce from her ex-husband; there are haikus about love, poems about the bonds between women and living in the South. At its core, Stringfellow observes, the book is intrinsically and unashamedly political, even in the personal. “The simple act of a Black woman sitting down to write a sonnet is a political act,” Stringfellow says. “It’s a revolutionary act.”

Many poems, though, are explicitly political, like those dedicated to Breonna Taylor, Tyre Nichols, Trayvon Martin’s mother, and Gianna Floyd, all who were killed by or whose loved ones were killed by racially motivated police violence.

“Until Black children aren’t being gunned down in America for simply ringing somebody’s doorbell; until Black children aren’t having the police being called on them by white women for just being outside, being loud, because all children are all loud; until we have basic civil rights in this country, my writing will always be political,” Stringfellow says. “It has to be. Nina Simone once said it’s the duty of the artists to reflect the times in which they find themselves. And unfortunately, I find myself in America in 2024 in some rather turbulent times.”

Yet Stringfellow also embraces the role of the writer as a bearer of hope. She notes how the other week, she saw a woman sitting at the Memphis Chess Club reading Memphis before Magic Enuff’s release. “It was so surreal to see my book out there [even two years later],” she says. “I hope the same happens with this poetry collection — that I see her, I see the cover, and a Black woman is reading her somewhere in Memphis. That is the ideal dream for me. That is the goal, to just bring a little bit of joy to Black women here in the South. Every book I write will be for the glory of Black Southern women.”

Indeed in her poem, “Hot Combs Catfish Crumbs and Bad Men,” she writes, “God can stay asleep/ these women in my life are magic enuff.”