In the world of sports, contemporary curmudgeons complain about nothing more than a young athlete they regard as having “style over substance.” Ever since Statler and Waldorf took their place in a private box high above The Muppet Show stage, a parallel mindset has prevailed among a self-appointed group of sports fans who resemble the rumpled pair in disposition, if not demographics.

These guardians of the game are often correct in their assertions about modernizing meddlers who strip away more of the essence of sports every year in a quest to make the games “relevant.” Ghost runners in Major League Baseball, the National Hockey League’s “delay of game” penalty, the National Basketball Association’s new preoccupation with replay, and the National Football League’s new everybody-gets-a-turn overtime rules are the most flagrant examples of the game-show gimmicks that these curmudgeons find so abhorrent.

One showbiz element in modern sports that the traditionalists are completely wrong about is the idea of showmanship. The Statlers and Waldorfs of the sporting fraternity often assert that flash or panache on the playing field demonstrate the lack of fortitude or professionalism of a particular participant. But decades before the good old days for which the when-it-was-still-just-a-game guardians opine, was an era when professional sports and popular entertainment were not so disparate. That was the age of Memphis’ own “Parisian Bob” Caruthers.

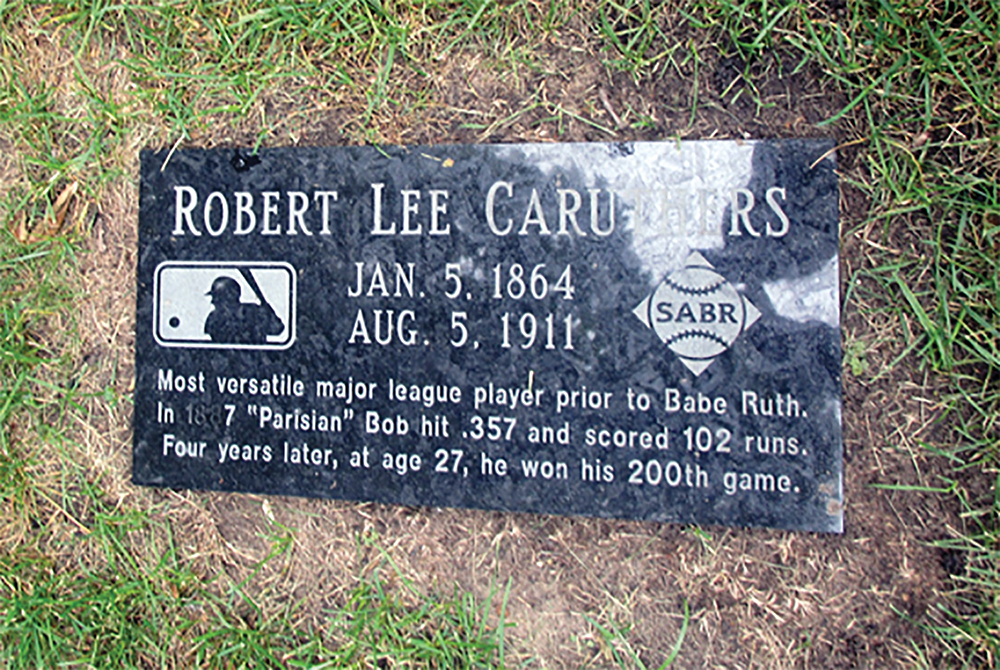

Style and guile were the substance of this well-coiffed and diminutive dandy of a pitcher. Pitching in the 1880s and 1890s, Caruthers won more than 200 career games and completed all but a dozen of the games he started. His career winning percentage of .688 is the highest of any big league pitcher before 1950 and second only to Yankees legend Whitey Ford (1950-1967) on the all-time list. Caruthers, like the 5’10 Ford, relied on excellent control and an array of off-speed pitches to befuddle opposing batters, rather than relying on raw power. The most obvious difference between the two is that Ford is in Baseball’s Hall of Fame while Caruthers, inexplicably, is not.

On Deck

Robert Lee Caruthers was born on July 5, 1864, in Memphis, which was then occupied by the Union Army during the Civil War. “Bobbie,” as he was known in his youth, was the third of four children born to John and Flora (McNeil) Caruthers. John Caruthers was one of Tennessee’s most highly regarded jurists of the 19th century. His uncle Robert Looney Caruthers had served on the state’s Supreme Court and founded Cumberland University as well as its law school, one of the oldest in the South.

Caruthers was small and sickly throughout his childhood, preventing him from partaking in many of the pleasures that came with life in a prominent family in late 19th century Memphis. In 1877, the Hon. John Caruthers decided to move his family north to Chicago, seeking out a new start after the death of Robert’s younger sister Emma, who died at the age of 9 after an extended illness.

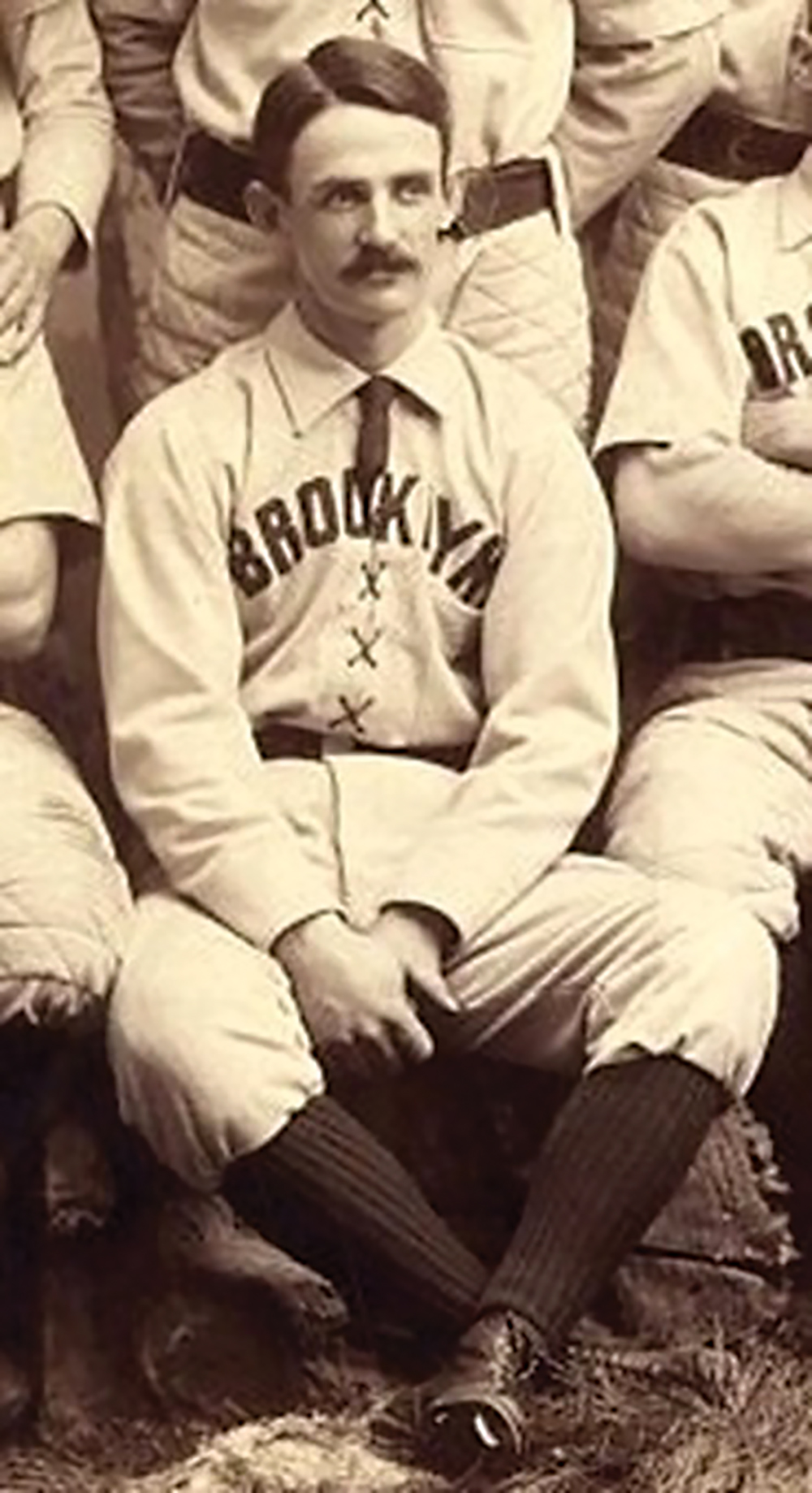

As young “Bobbie” reached adolescence, his body grew stronger. Paralleling the development of his generational peer Theodore Roosevelt (who also suffered from a series of childhood ailments), Caruthers grew into a strong and sinewy man during his teenage years. Though he only stood 5’7 as an adult, Caruthers boasted a trim and muscular 140-pound physique, which looked something like a gymnast’s.

He applied himself to baseball and soon became a star. Caruthers was a crafty pitcher, robust hitter, and elite fielder for amateur clubs on Chicago’s North Side. At age 19, he signed his first professional contract with a club in Grand Rapids, Michigan. A little more than a year later, Caruthers debuted in the Major Leagues, playing for the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in September 1884.

Bobbie up to Bat

Caruthers was a genuine overnight sensation in St. Louis. Playing roughly halfway between his hometown of Memphis and adopted home of Chicago, Caruthers asserted himself in his first full big league season as the best pitcher in the sport. Caruthers won a league-leading 40 games and posted a 2.07 earned run average (ERA), the lowest figure in the league. He pitched 483 innings that season, more than twice as many as Major League Baseball’s innings-pitched leader in 2019. Caruthers followed up his rookie campaign with another 30-win season in 1886 while posting impressive numbers as a hitter as well. He batted .342 in his second season, making him the second-best hitter for average in the American Association. In both seasons, the Browns won the pennant in the American Association, largely due to the pitching prowess of their young ace.

The diminutive Caruthers had a unique approach to pitching. Unlike many other aces in baseball history, he did not throw particularly hard. Instead, he relied on psychology and a wide range of unconventional pitching deliveries to confuse hitters, manipulating the speed and location of his pitches to trip up big league batters.

The young ace’s flair for the dramatic extended beyond his approach to pitching, too. Indeed, Caruthers was known to be a natty dresser with a taste for expensive clothing as well as fancy food and drink. He wore a stylishly groomed moustache and kept his hair neatly trimmed at all times.

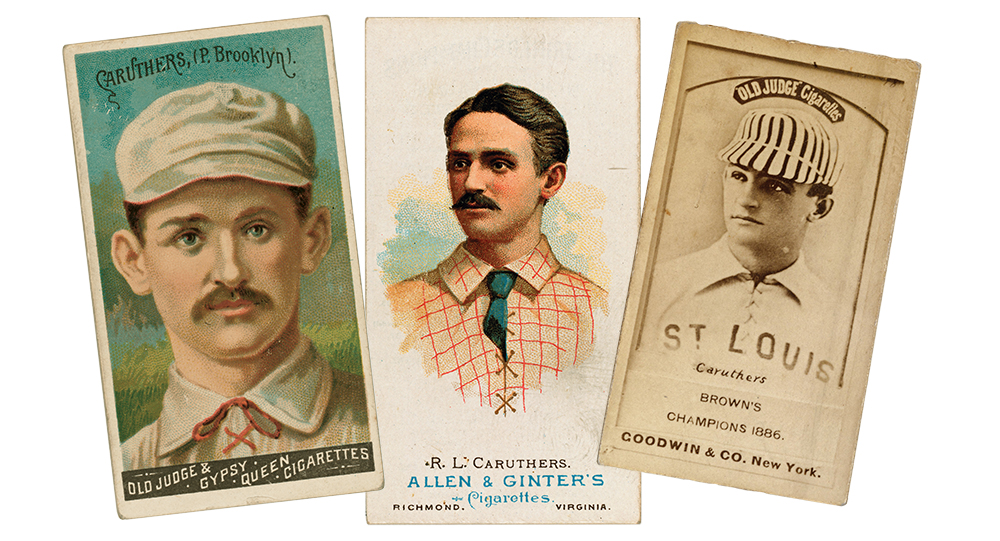

“Parisian Bob”

After games, Caruthers frequented saloons, poker tables, and pool halls. He earned the nickname “Parisian Bob” after the 1885 season, when he traveled to France with a teammate for an extended vacation in the City of Lights, all the while conducting contract negotiations through telegrams across the Atlantic. In the end, Parisian Bob agreed to play for a then-record $5,000 a year in 1886, which did nothing to quell his appetite for high-end clothing and evening entertainments. His desires for the many pleasures of the flesh may have been the result of immaturity. They may have also been evidence of an accurate self-appraisal of the number of opportunities he had left to enjoy such things. It was widely reported that Caruthers suffered from a heart ailment, likely the result of his childhood illnesses. To borrow the suddenly overused phrase, Caruthers may not have been here for a long time but was certainly here for a good time.

Despite his growing off-the-field reputation, Parisian Bob continued to excel on the field. In 1887, Caruthers won another 29 games and led the Browns to their third consecutive pennant. Parisian Bob put up his best season at the plate as well, finishing in the top 10 in the American Association in hitting with a .357 average. The Browns played the National League champions from Detroit in a traveling “World Champions Series” that was played in several cities. Caruthers and his teammates had played in more modest iterations of the event in 1885 and 1886, losing the first time while winning the latter series.

The 1887 event, by contrast, was a much more heavily promoted and elaborate spectacle, which showcased professional baseball at stops across the eastern half of the United States. The Detroit Wolverines overwhelmed the Browns throughout the 15-game series, allegedly due in part to the Browns’ carousing in the after-hours. Caruthers, well known for his enthusiasm for extracurricular activities, took the blame from team owner Chris von der Ahe, who sold his star pitcher to the Brooklyn franchise in the American Association for a reported $12,500 (roughly $375,000 in 2021 dollars). At the time, the price that Brooklyn paid for Caruthers was the highest one ever paid for a ballplayer.

Bobbie and the Bridegrooms

In early 1888, Parisian Bob settled down in his typically grand fashion. He made Mary “Mamie” Danks, a 22-year-old Chicago debutante originally from Lexington, Kentucky, his bride. Friends and family lavished the stylish young pair with wedding gifts reportedly worth in excess of $4,000 (roughly $120,000 in 2021 dollars). Shortly after Caruthers’ lavish wedding, his new team in Brooklyn adopted the moniker “Bridegrooms” for the season to capitalize on their star pitcher’s off-season notoriety.

Almost singlehandedly, Caruthers made the Bridegrooms a contender. He won 29 games in 1888 and posted a second 40-win season in 1889, transforming the perennial also-ran into a pennant winner in 1889. Unfortunately, Caruthers’ baseball skills deteriorated rapidly in the early 1890s. A half-decade’s worth of 300-plus inning seasons (few pitchers in 2021 even throw 200 innings in a season) strained and atrophied his right arm, which had recently been the most valuable weapon in baseball. Caruthers’ win total plummeted from 40 in 1889 to 23 in 1890 to just two in 1892, while his ERA ballooned to nearly 6, making him one of the least effective pitchers in the National League.

After a brief stint playing outfield for the Cincinnati Reds, Caruthers’ big league career came to an end just weeks before his 29th birthday, when the Ohio club released the one-time superstar. All told, Caruthers won 218 games in a 10-year career while losing just 99.

Caruthers spent much of the late 1890s trying to revive his baseball career, playing in a half-dozen minor league towns. Unfortunately, his right arm never bounced back. He played his final professional games in 1898 for a short-lived independent team in Burlington, Iowa.

After the Show

Following his playing career, Parisian Bob drifted through baseball circles, working primarily as an umpire. On the field, the flamboyant former pitcher often got into scrapes with players and managers, which did nothing for his umpiring career. Neither did his apparent troubles with alcohol, which had developed over the course of his career.

Drinking likely exaggerated the lifelong health problems Caruthers had suffered. The former star worked his way steadily down the baseball food chain over the course of the 20th century’s first decade. He served in 1902 and 1903 as an American League umpire. By 1911, he was working the “Triple-I” League, a Class B circuit that consisted of teams in Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa. The former big league ace had earned the reputation as a thin-skinned and foul-mouthed official by that time and was apparently out of pocket, a fate suffered just as frequently by athletic stars of the 19th century as those of the 21st. Caruthers, his wife Mamie, and their two children took up residence at his in-laws’ home in Peoria, Illinois, after moving out of a three-family rental unit in Chicago.

At the Old Ball Game

Caruthers’ physical and mental health declined rapidly in 1911. Apparently, he suffered what the contemporary press referred to as a “nervous breakdown” that spring. Soon thereafter, he was sentenced to 20 days in an Illinois state work-house for public drunkenness. Before serving his sentence, Caruthers fell gravely ill and died at St. Francis Hospital in Peoria on August 5th. He had just turned 47 years old.

Caruthers was buried in an unmarked grave in Section N of Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. Memory of Parisian Bob faded as those who followed his career became ever fewer in number. A new generation of baseball fans, particularly those interested in the early history of the sport, have helped to revive interest in the colorful star. In recent years, members of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) provided him with a headstone worthy of his legacy, more than a century after his death. In 2018, SABR members installed a beautiful marker in Caruthers’ honor, which cited the Memphis native as “baseball’s most versatile player prior to Babe Ruth.”

While SABR is rekindling the memory of Caruthers, the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Early Baseball Committee has an opportunity to further cement Parisian Bob’s legacy. In December 2021, the committee meets to select new inductees into the Hall; the committee meets every five years to weigh the merits of potential inductees from the 19th and early 20th centuries. It seems like momentum has started to swing in Caruthers’ direction and, hopefully, the electors make use of this opportunity to honor one of the game’s greatest talents. Though Caruthers’ career was short (he played 10 seasons, the minimum for induction), he proved to be one of the most effective and interesting players of his generation.

Clayton Trutor holds a Ph.D. in U.S. History from Boston College and teaches at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta—and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (University of Nebraska Press), which is available now for pre-order.

Body and Mind

Body and Mind