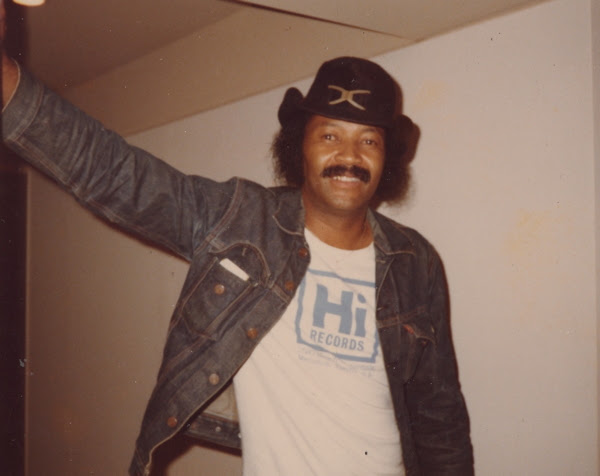

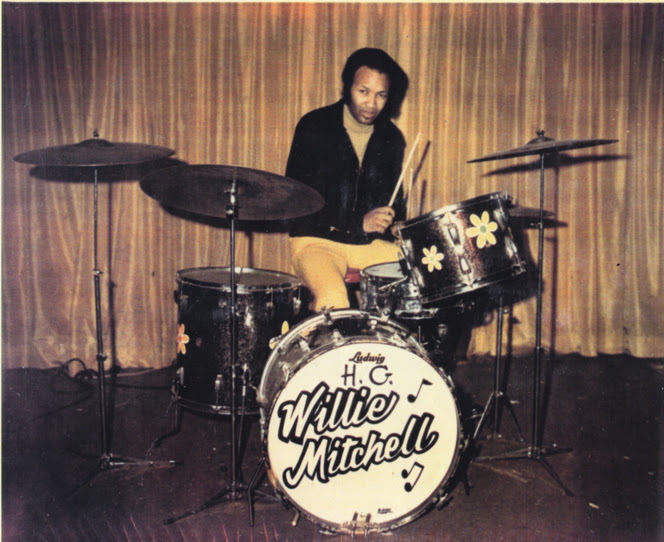

With the death of drummer Howard Grimes at age 80 on Saturday, Memphis and the world lost much more than a rock-solid master of the groove. Dubbed “Bulldog” by the producer Willie Mitchell, he was indeed a master of the driving beat, with not only perfect metronomic time, but an artful sense of space in his rhythms. But he was also a bridge between many worlds and eras in Memphis music, lending his feel to records and bands over six decades.

Last year, the Flyer devoted a feature to the autobiography he wrote with Preston Lauterbach, Timekeeper: My Life in Rhythm (Devault Graves). But in the interview conducted for that article, Grimes revealed much more about his life than space would permit at the time. Here then are further musings from the man himself, as he sat in Scott Bomar’s Electraphonic Recording studio, where Grimes had done so much to revive his musical life in recent years. Indeed, his work with the Bo-Keys, backing the likes of Percy Wiggins and Don Bryant, not to mention sessions with the Hi Rhythm Section at Royal Studios, added up to a full fledged Renaissance for Grimes over the past twenty years. As Bomar notes in The Commercial Appeal‘s obituary, “Anyone who played with Howard knew that he was a very special drummer and special person.”

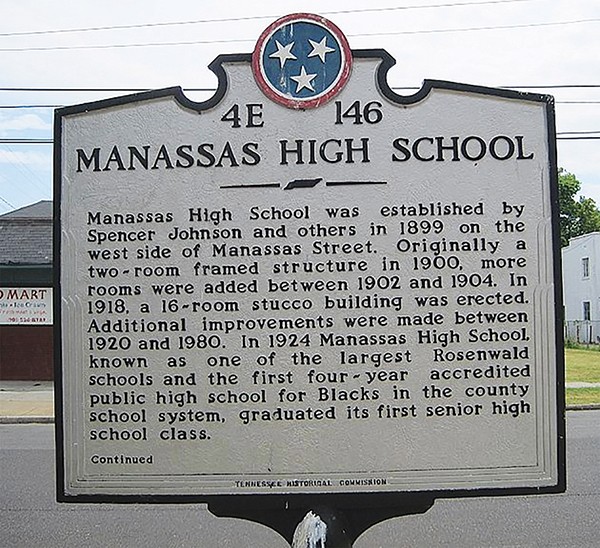

Memphis Flyer: In your book, you describe how you heard the Rhythm Bombers, the Manassas High School band, and how thrilled you were to finally attend there and study under band director Emerson Able.

Howard Grimes: Yes, I went to Klondike Elementary first, through the eighth grade. But then I went to Manassas. Some of the greatest musicians came out of there, like Hank Crawford, who I knew well. And James Harper, a trombone player I knew well, who knew my family and parents. Both of them went to play with Ray Charles later. When they used to come home, they would sit and talk to me and tell me about my work: “Hey, they know you out there, man. Just keep up the good work.” So that was a great inspiration, that they were keeping the big boys informed about me.

What other memories do you have of your early days of discovering music?

The first Caucasian people I saw on Beale Street were Sputnik Monroe and Billy Wicks. They were wrestlers. And Dewey Phillips. He was working on Main Street, spinning records. I’d be on Main Street shopping or something, and I’d go down there and see his little gadget where he was playing music. The first record I heard there was Carl Perkins, “Blue Suede Shoes.” That’s the way it started. That’s when the men were drinking Gold Crest 51, Falstaff and Stagg beer. That’s what they were drinking, listening to that Carl Perkins.

Did you play in church?

I played in church for a while, but they pulled me out. Because I had that beat! They snatched me out so fast! But the basis of this city at the time was all Christian. I was listening to Sam Cooke and the Swan Silvertones, the Caravan Singers out of Chicago, the Clark Sisters. All of those were my favorite groups. Then when I started playing with Ben Branch, WDIA used to have what they called the Starlight Revue. It was downtown at Ellis Auditorium, originally. You see how far back I’m talking. That’s where all the stars were congregating together. It was such a joyful time. And they had the blues too. So the people who didn’t want to stay for the blues, they would leave before we started the blues show. It was great. I got a chance to play both sides. The Starlight Revue and the Goodwill Revue. The environment was just beautiful.

Were there many white people attending?

Integration hadn’t really set in. When I started at Satellite Records [in 1960], Chips Moman had already organized Caucasians and African Americans in the band, but nobody knew it. Steve Cropper and them were already there, but when he pulled in Floyd Newman and Gilbert Cable, and then Marvell Thomas and me, he made a combination, and everything gelled.

When we were at Satellite, I didn’t understand how we could all work together inside, but when the session was over, we couldn’t all come out the same way. So Steve would stay in, and we’d come out, just us. And one day I said, “Why can’t we all walk out together?” Floyd said, “Howard, it hasn’t been integrated yet.” But it was integrated inside. And it was better because that was so much fun. There was so much we learned from each other. We were brothers. We’d take money at lunch time, and Chips would say, “Okay, we’ve got a lunch break for an hour.” Everybody would piece together the little change they had, and we’d buy baloney and a long loaf of bread and mustard and stuff, and we’d come back and all sit down and make sandwiches. And when the time was up, we’d go back to the session, the next song.

You played on a lot of tracks by the Mar-Keys at Satellite, didn’t you?

I didn’t cut “Last Night.” A drummer named Curtis Green cut that single, but I cut two albums, the Do the Popeye album and the Last Night album. Floyd Newman had also gone to Manassas and put a band together, and I started working at Plantation Inn with him and Isaac Hayes. Floyd showed me so much. He was like Willie, before I met Willie. Floyd’s ears were always open. He studied you and listened. I never knew what I had until I played a certain beat one night. Floyd said, “Man, can you remember the beat you just played? We’re gonna go to the studio tomorrow and lay that track down.” And that turned into “Frog Stomp” [by the Mar-Keys]. And that was my signature. So that’s how I found myself. That was the beginning.

There are some great deep cuts on those Mar-Keys albums. Like “Sailor Man Waltz.”

That was my favorite. When I got with the Mar-Keys, there used to be a Ray Charles record called “Blues Waltz.” My mother loved that record and used to play it all the time. But it was out of sync. The drummer was playing one pattern, and she was popping her fingers to another. And then Ray Charles was playing another on piano. So you had these three different patterns going. And I’m listening, but I’m listening hardest to my mother. So what happened was, Mr. Stewart had bought a new organ, because the organ he had in there at first was a little one. It was good, and Booker T. Jones was getting good stuff out of it, but when he bought that Hammond B-3, Booker T. was learning, pulling all the stops, and I was hearing the sounds.

We were about to do a session, and I was listening to what he was doing, as he was feeling his way through this organ. And Marvell was a jazz pianist, listening to Ray Charles all the time. So Booker T. started playing this 3/4, 6/8 time rhythm, and I heard Marvell playing the line bom bomp a dee daa…da dee daaah. So I couldn’t think of anything but “Blues Waltz.” Ray Charles. I knew, with them being jazz musicians, that they were into all that. They could play pretty much anything. So they came up with that idea, and I heard the pattern. So I took the beat off “Blues Waltz” and it fit what they were doing. It was one of my favorites. It was a great record, but we only played it once, while we were recording it.

You were eventually hired by Willie Mitchell, of course, and became part of the Hi Rhythm Section, with the Hodges brothers. It seems that you were very tuned into the production process while working at Royal Studios.

When I did a session, I never left the studio. Most of the guys would be anxious after we finished, and want to leave and go other places. They wanted to hang out with the girls. I wanted to learn all I could learn, because I knew that would one day benefit me. And Willie was always telling me if I was going to be good, I needed to know it all. Learn it all! he said. Because you’ve been in it too long. So he was teaching me, and everything he showed me. I come from him and all the rest of the people who taught me.

The [Hodges] cats were so soulful, all I had to do was listen. I could tell where a groove was just by them playing. And once I sat down and played, it all locked in. So Willie noticed that about us, and when he accepted a track, he’d play it back and check everybody and see if they were in the right place, in time, and every note. And I used to sit there and watch him, to see what he was going to say. And then during playback, all of a sudden it would hit him, Bam! And he’d say, “Hey Dog! There it is! There it is!” He called me the Bulldog.

So we’d know it was there. “Dog! Hey Dog! I hear ya!” That’s the way he’d do me, so he always was a big inspiration to me. And I learned so much by following his footsteps and listening.

Willie told me before he died, “Howard, one day you’re gonna be doing what I’m doing.” He said, “Don’t laugh. My boys go a long ways. You can produce, you know a hit when you hear it. You can write. But I want you to pay attention to the lyrics.” I never used to listen to lyrics. I was just trained in the music, because Memphis is about instrumental music. But artists are storytellers. I started listening to what they were saying, and everything made so much sense. And now, I listen to the lyrics and I know what to do.

The time after Hi Records folded was a dark period for you, wasn’t it?

The company took a turn in ’77. And my wife divorced me. I lost my home because I ran out of money. I was ashamed, because people had looked at me from another side, growing up playing, and everybody was with me, and then all of the sudden, this generated all this failure. I didn’t know what to do! I was ashamed to ask people for help. I was slowly dying and didn’t know it. I was dying from hunger and starvation. My utilities were turned off. I was in the house, I wouldn’t come out, nobody was seeing me, because I was ashamed. When I was accepted, everybody knew me. I could walk in a club, “Howard!” I could sit in, play with the band, and it was great! But something happened and my life took a turn.

So I had an out of body experience. I died in the house. I didn’t know what had happened until I went to a pastor afterwards. I was on my couch and I drifted off, and I was in this dark tunnel and I saw a light, and I heard this voice say, “Walk to the light.” I started walking. When I got up, the light was so bright, it started to beaming where I could see, and when it got all the way down to where I could actually see, I saw this figure, a man in a white robe, arms out like that. I couldn’t see his face, like I’m looking at you. But the head set over the body was the sun. I walked up in his arms. And I heard a voice say, “You have obeyed me well. I’m gonna send you back.” I was saying, “I don’t want to go back!”

He said, “No, you must go back. I command you. Don’t go down there running your mouth, or they’re gonna call you crazy.” I’ve never forgotten it. And when I heard that, I woke up. It was kind of strange to me, because I didn’t understand. I looked at myself, I touched my face, I touched my hand, looked at my head. I went in the restroom, I looked in the mirror, and I saw the thorns on my head, my face. The first time I saw it, I shook my head and walked away. Then I came back and looked again, and it flashed a second time. I walked away and came back. When I saw it the third time, I knew. I said, God is in me. So I had his spirit.

My best friend came around, and when I opened the door, he said, “Boy! Howard, you’re glowing!” I couldn’t see anything. But he was so happy, and said, “You’re glowing so much I can’t even look at you! Howard, God got you!”

That was in ’83. Later, I got the idea to write a song, and Scott engineered it. God gave me a song called “Sin.” He said, “If you’re living in sin/You’re not going to win/You’ve got to ask God for forgiveness/If you wanna make it in.” When we wrote the song, then I let a pastor hear it, and he told me, “I’d like to have a copy of that song to play when people are coming to church.” It touched him.

So we recorded it here at Electraphonic, and the back side is “My Friend Jesus.” Where would I be without my friend Jesus?

Alan Nahigian

Alan Nahigian